Box sets » Welfare trends

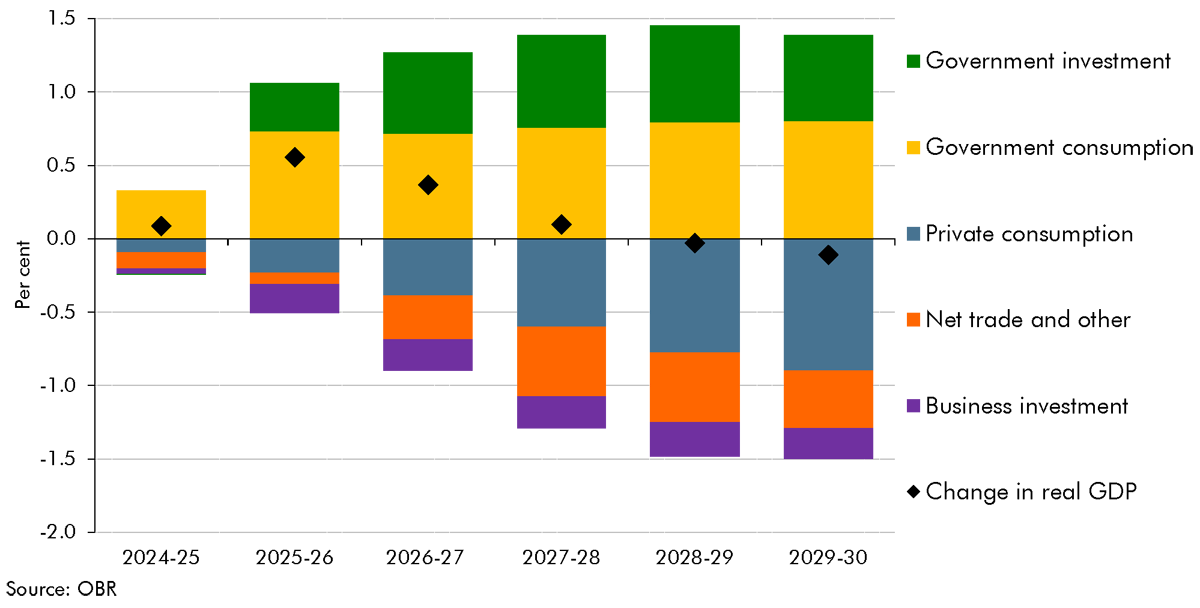

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our October 2024 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our forecast to account for fiscal loosening and considered the effects of changes to taxation and increases in public investment.

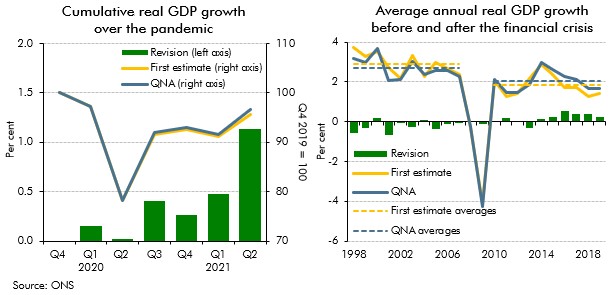

As we finalised our pre-measures forecast on 26 September, our forecast did not include the Quarterly National Accounts released on 30 September 2024, which contained Blue Book 2024 consistent revisions. This box examined the potential implications that including the latest data may have had on our forecast. We judged that the data revisions would have provided limited new information on current economic conditions, leaving our economic and fiscal forecast broadly unchanged.

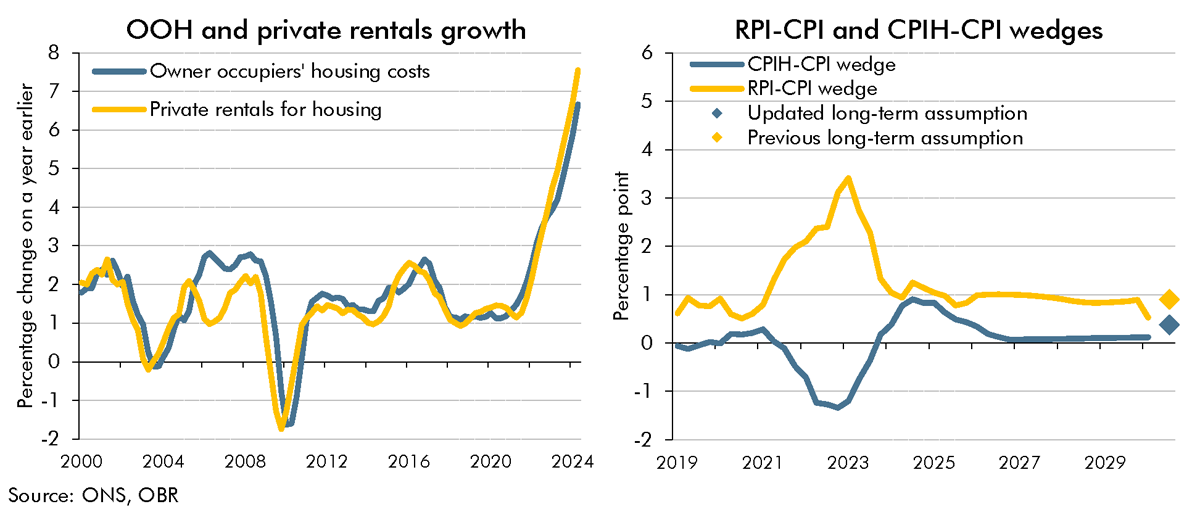

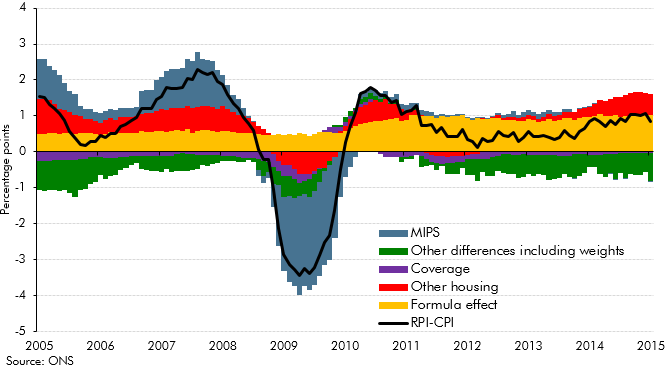

As as result of the shortcomings with the methodology for calculating the Retail Prices Index (RPI), the ONS's current plans are to address these by bringing the methods and data sources from the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH) into the RPI in February 2030. In this box, we explained how this change would impact our estimate of the long-run difference between RPI and CPI inflation.

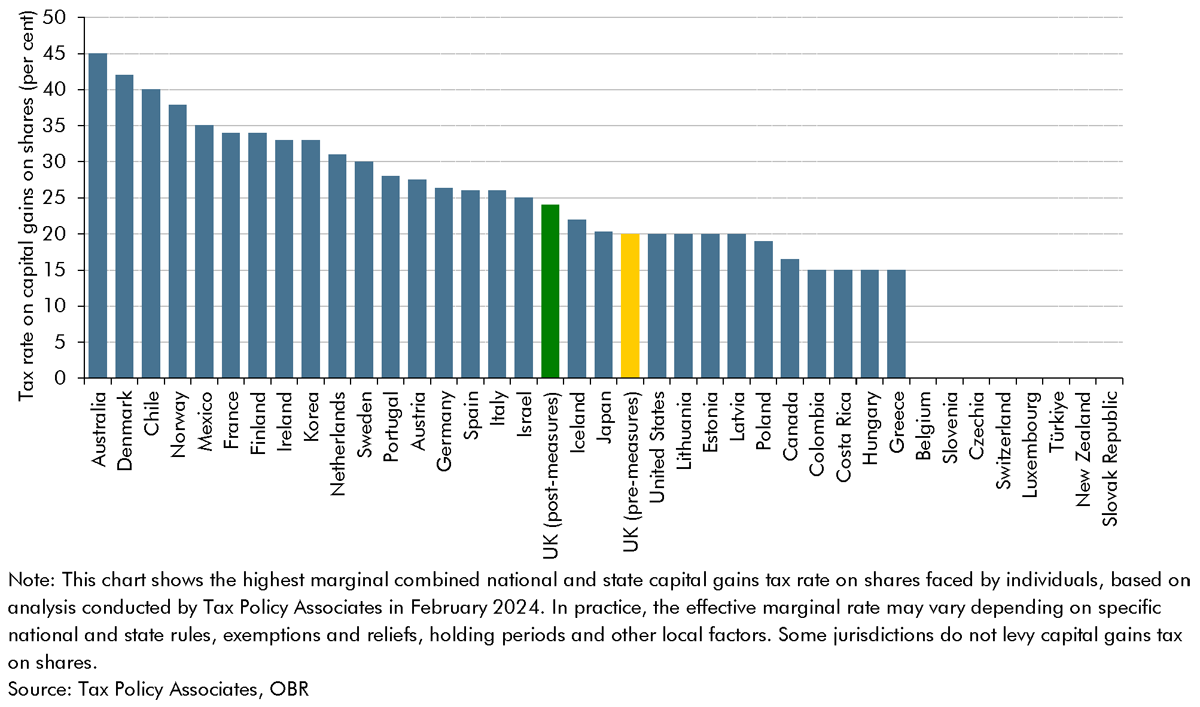

The capital tax measures announced in the October 2024 Budget affected an overlapping set of taxpayers and tax bases, mainly across capital gains tax, inheritance tax and income tax. In this box, we considered how individuals can respond to an increase in a capital tax liability, and what we assumed about these behaviours in our costings for capital tax measures.

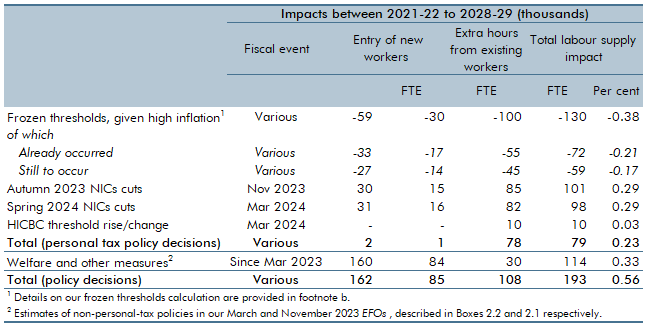

The OBR, the Treasury, HMRC, DWP, DfE and DHSC have established a set of monitoring and evaluation arrangements for the 13 policies for which impacts have been explicitly incorporated in our potential output forecast as indirect effects since the Spring Budget 2023. In this box, we provided an update on monitoring and evaluation of these policies, and used the new evidence to assess how implementation and delivery align with our original judgements for indirect effects across the forecast horizon, culminating in a downward revision to labour supply in 2028-29 of 0.04 per cent.

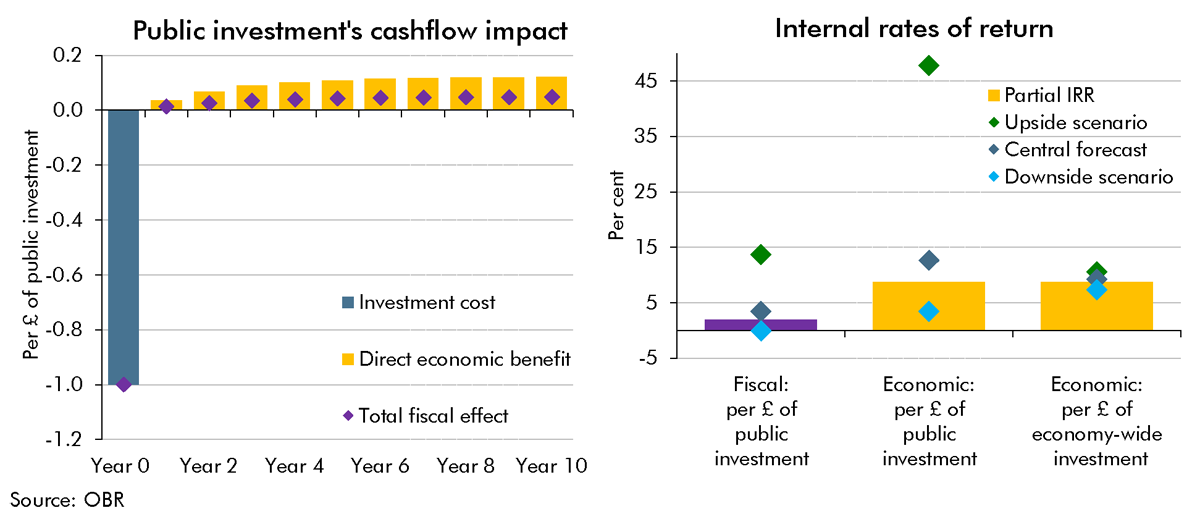

A key uncertainty around the long-run impact of the Budget's plans for higher public investment is the extent to which the public capital stock is a complement to (or substitute for) business investment. This Box provided scenarios in which the future business capital stock was higher or lower than we had assumed in our central forecast. We showed these scenarios' impacts on potential output in 50 years' time and the implications they had for different measures of the internal rate of return on investment.

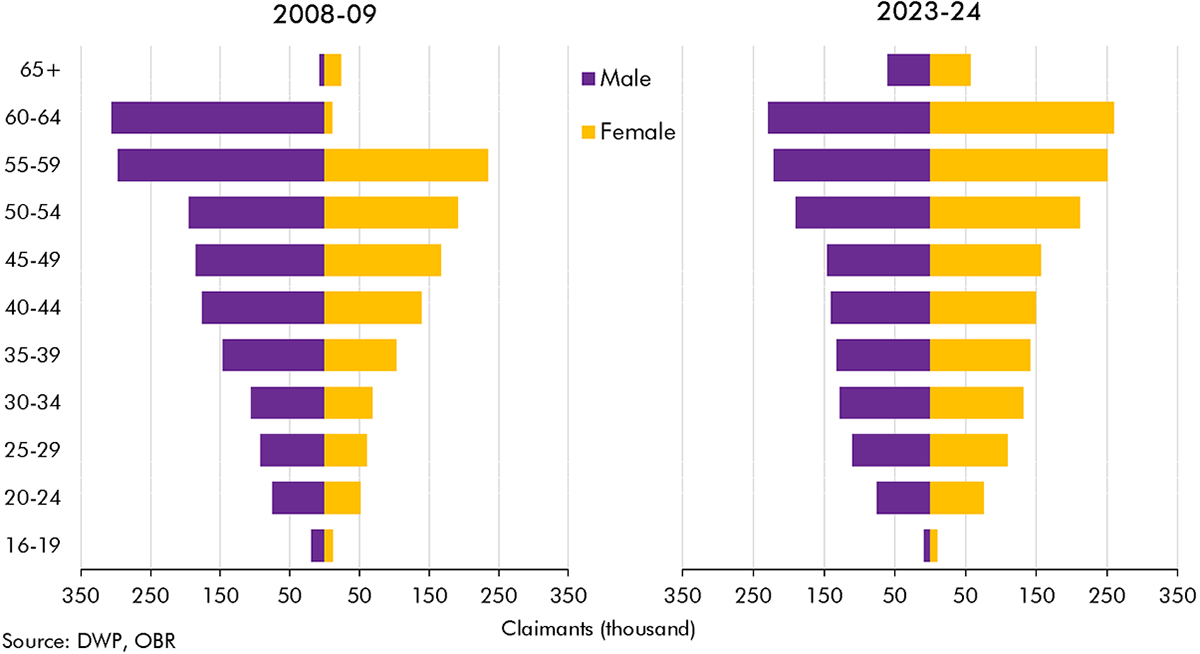

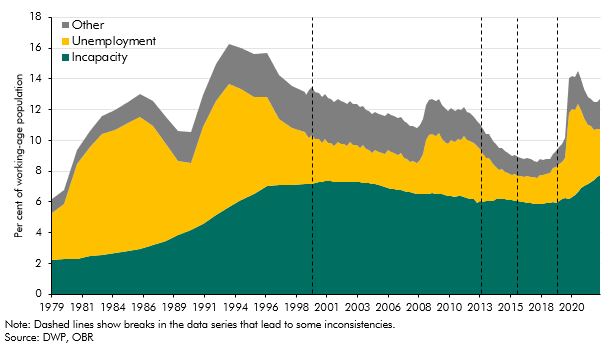

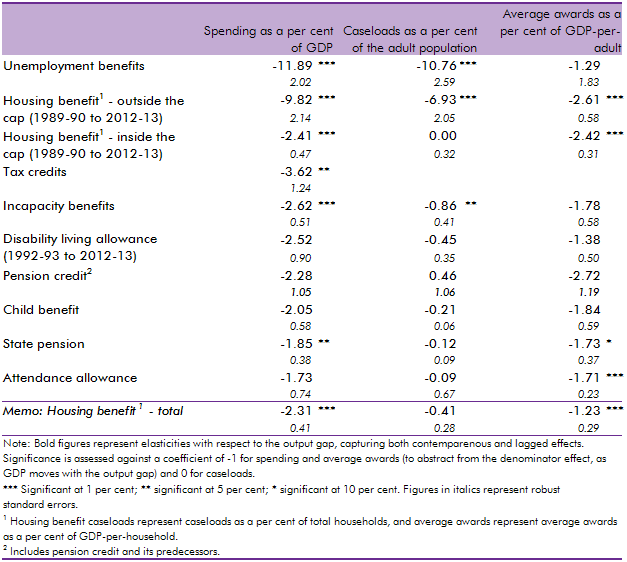

The rise in incapacity benefits after 2013-14 coincided with a rise in the state pension age. In this box we explained how much of the change in incapacity benefit caseload was explained by rises in the state pension age and the ageing of the population.

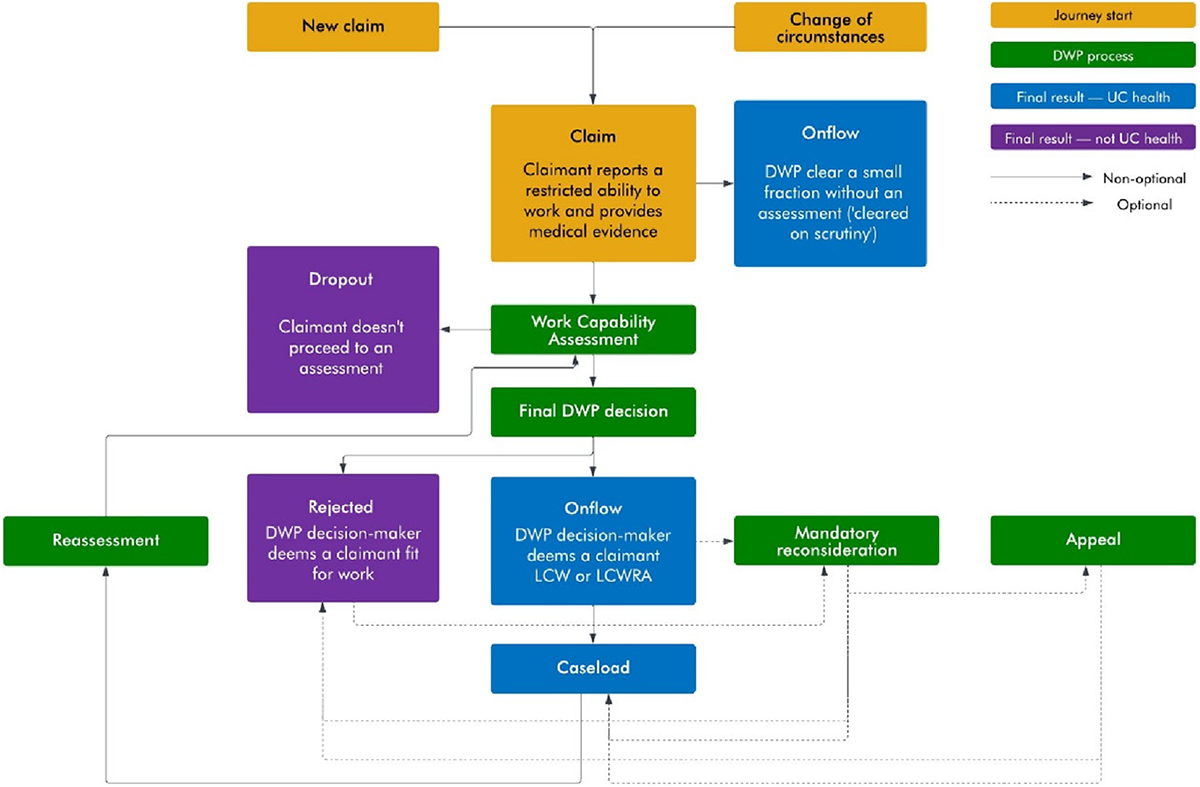

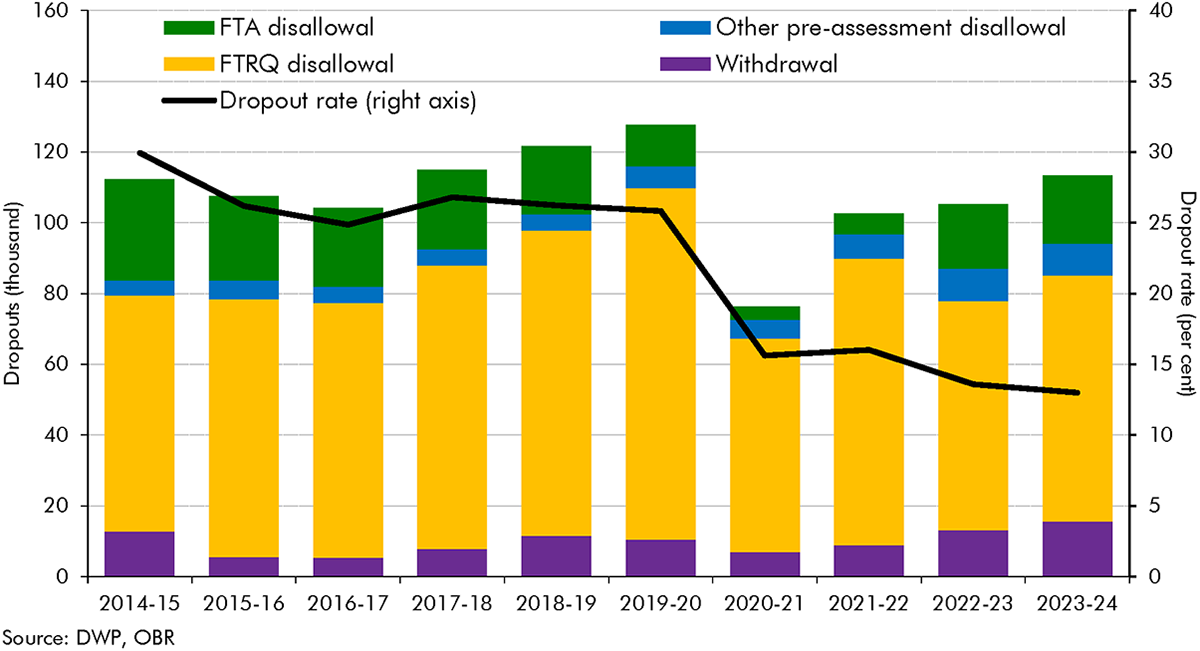

There are several stages before a claimant joins an incapacity benefit. In this box we explained the stages involved in joining either the less-severe (LCW) or more-severe (LCWRA) groups under universal credit, and differences in the predecessor employment support and allowance benefit.

Both incapacity and disability benefit onflows have grown substantially since 2018-19. In this box we compared the different drivers of these respective increases in onflows and drew some lessons from the granular disability benefit data for how incapacity onflows may have been changing.

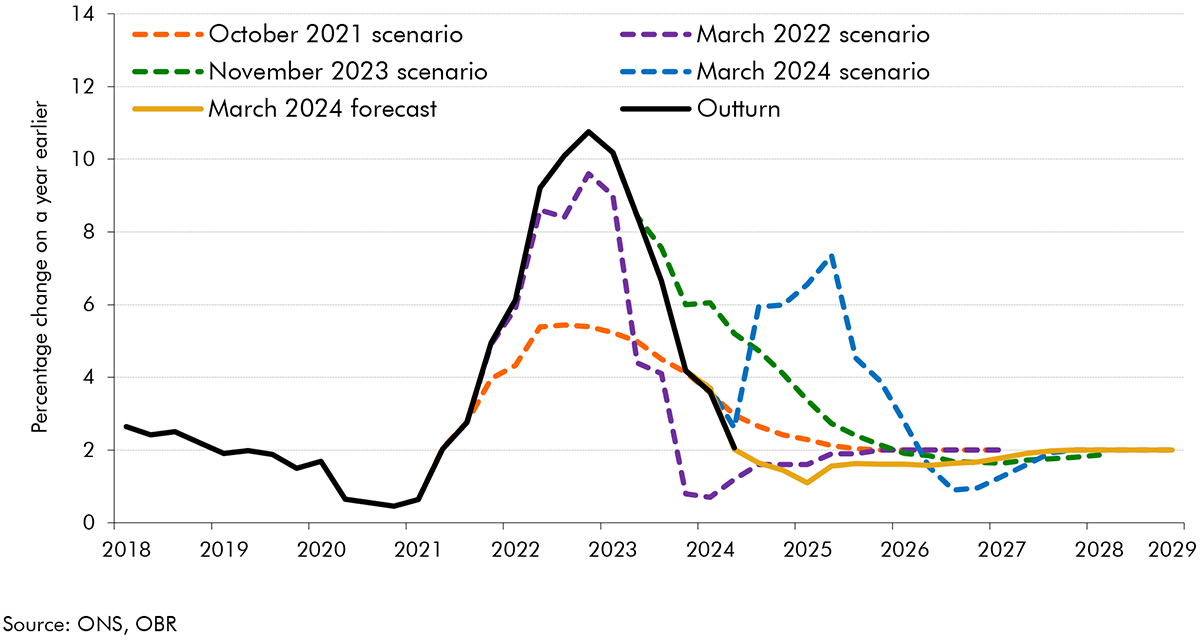

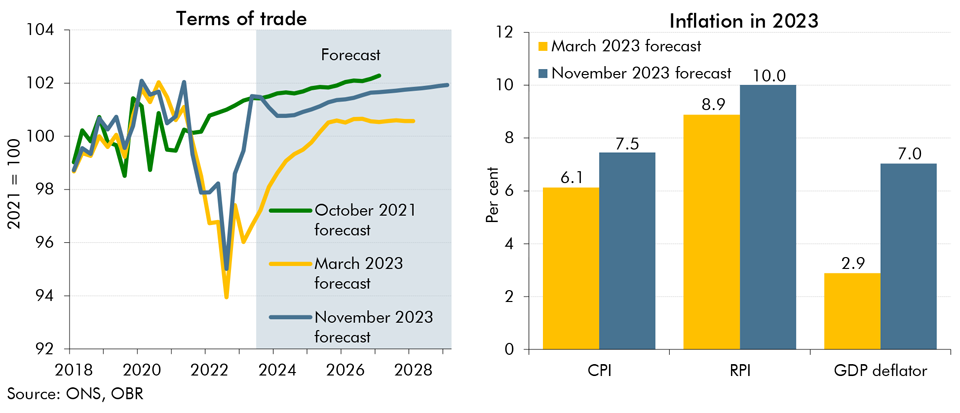

The outlook for inflation was highly uncertain at the time of our March 2023 forecast: the UK was experiencing the largest inflation shock since the 1980s, and the first significant shock in the era of independent inflation-targeting central banks. In this box, we reviewed the ways we have presented uncertainty in our successive EFOs, in particular our use of fan charts and scenarios.

Adaptation measures can significantly reduce the economic impact of climate change, but come with additional costs that add to the fiscal pressure of climate change. This box discussed the current state of adaptation investment within the UK.

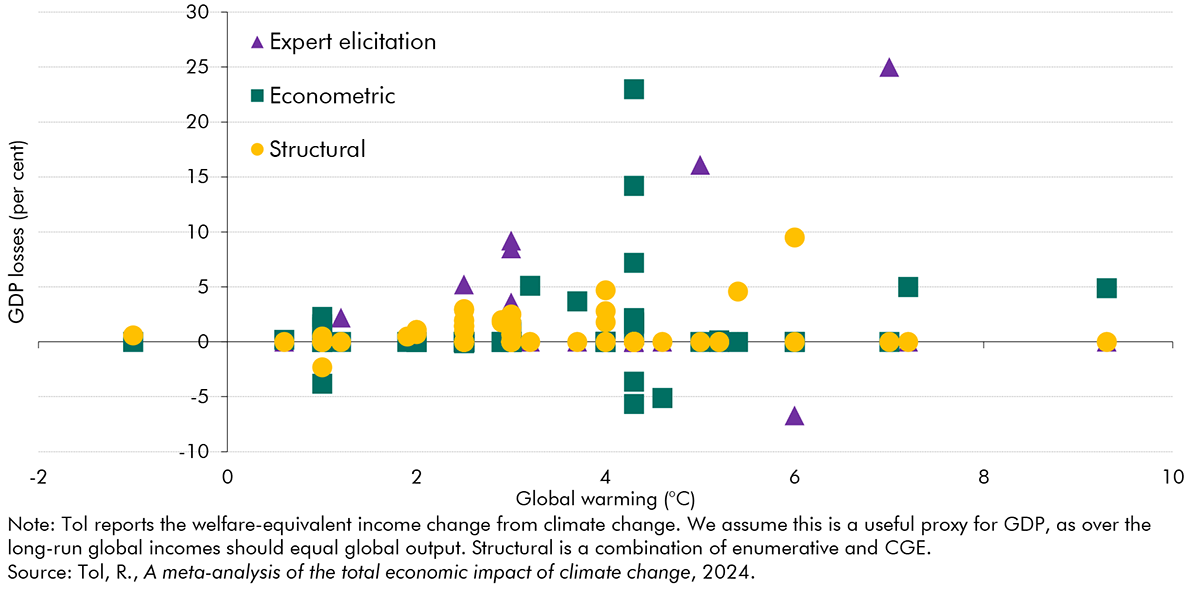

There is growing literature on the economic costs of climate change, where there is near-consensus on the negative impact on economic output but with a wide range of estimated losses. This box explored the the scale of, and reasons for, such differences and examined relevant UK studies in this context.

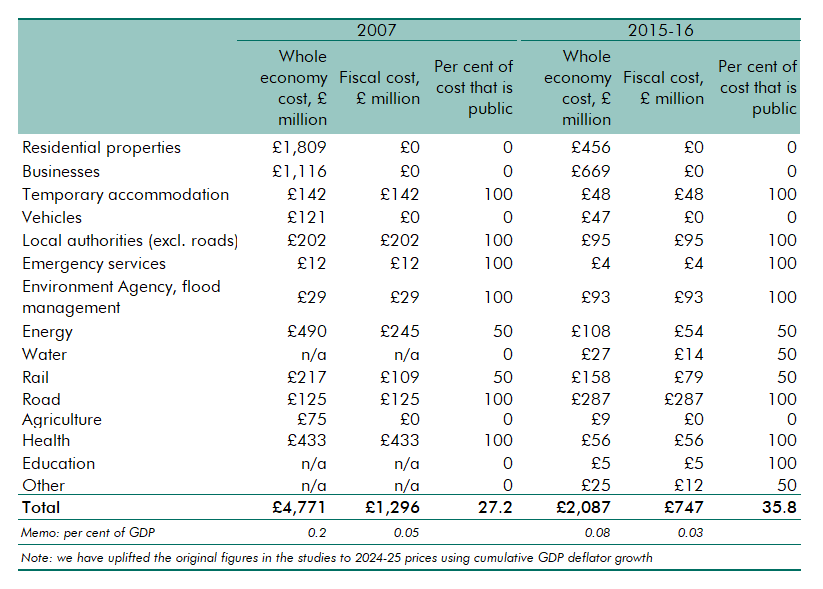

In 2010 and 2018, Defra and the Environment Agency produced reports exploring the costs of the 2007 summer floods and 2015-16 winter floods to the UK economy. In this box we used these numbers to estimate the direct fiscal costs of these flood events.

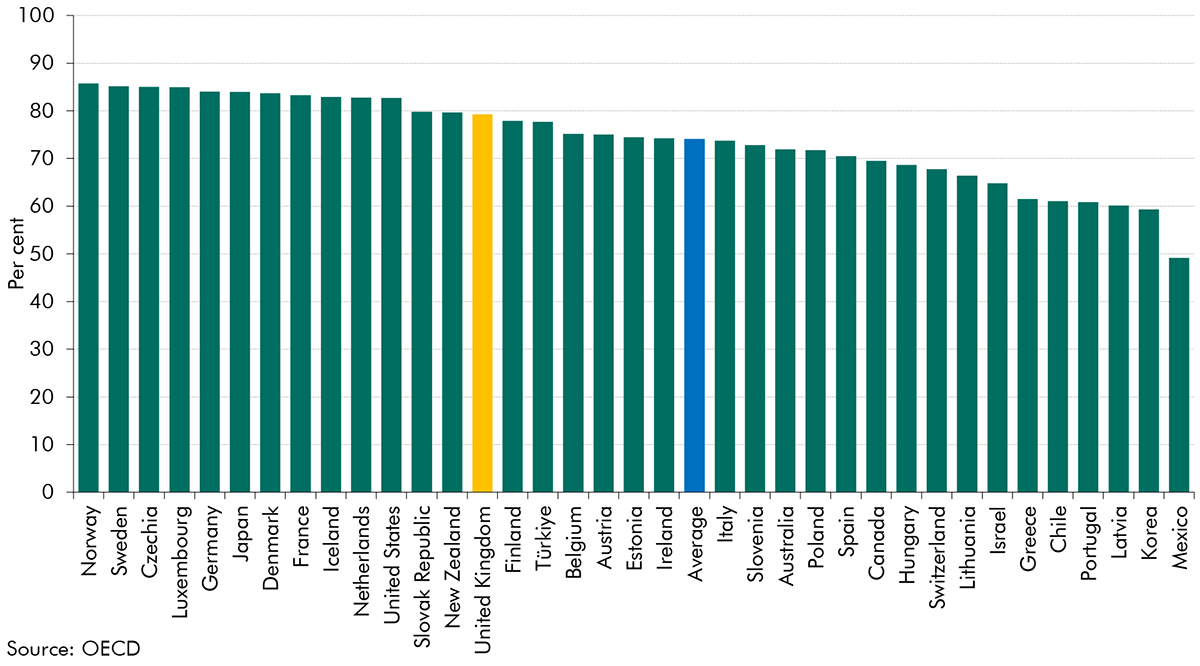

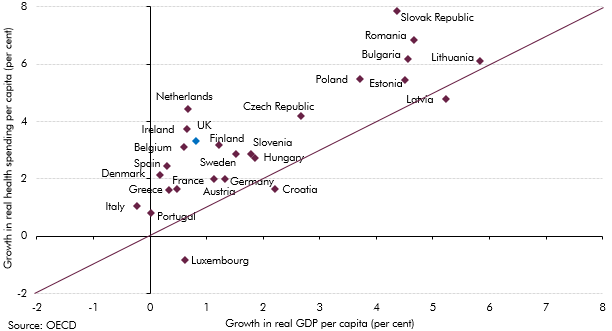

Our long-term fiscal projections focus on public spending on health, but private spending accounts for a significant share of health expenditure in the UK and particularly in other advanced economies. This box explored recent trends in private health spending in the UK and how this compares with other advanced economies.

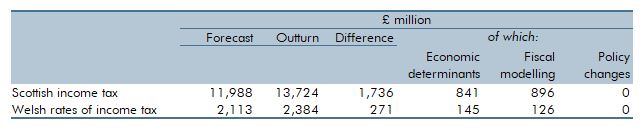

Income tax was devolved to the Scottish Parliament in 2016 and the Welsh Senedd in 2019. In this box we evaluated our March 2021 forecasts for 2021-22, and how they compared to the eventual outturn data. This was a particularly difficult period to forecast given the economy was recovering from the unprecedented impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The double-digit difference between our initial forecast and the final outturn, for both Scotland and Wales, is largely explained by the faster-than-expected post-pandemic recovery.

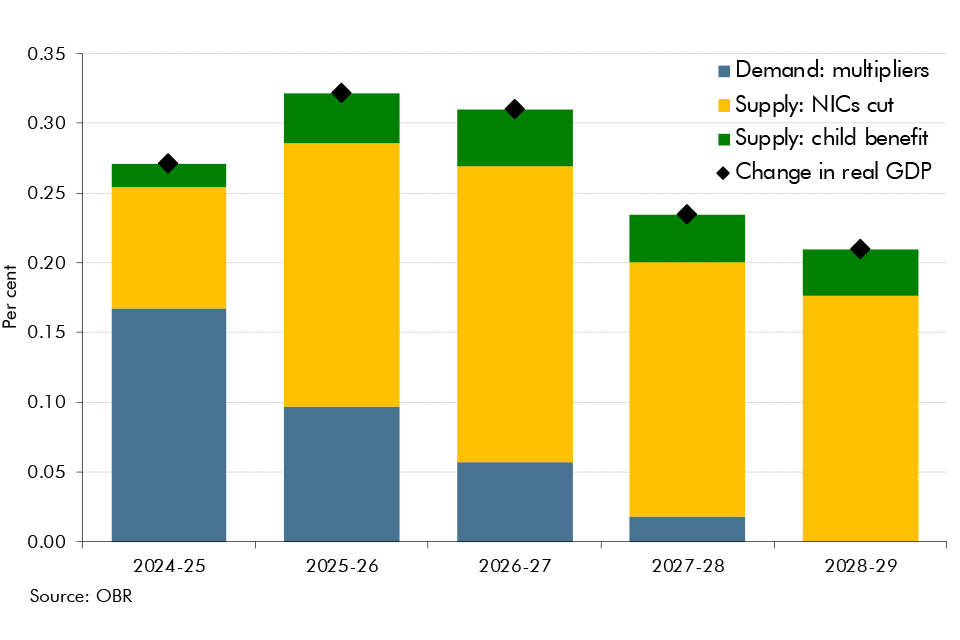

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2024 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our forecast to account for fiscal loosening and considered the effects of policy to boost employment on our potential output forecast.

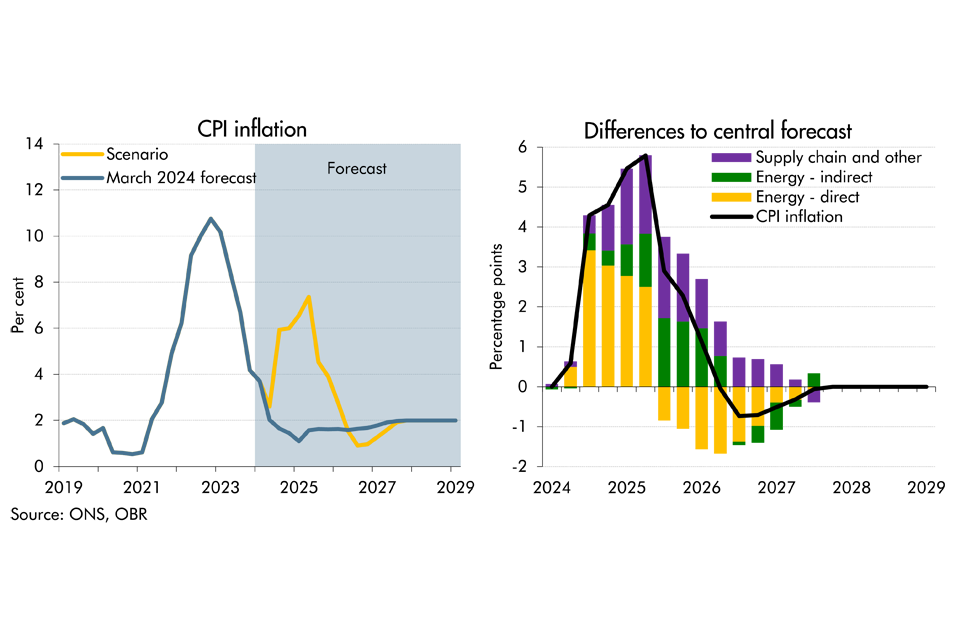

As tensions have risen in the Middle East, there has been increasing concern over the possibility of a wider escalation in the region and its implications on the UK economy. In this box we considered the economic growth and inflationary implications of an adverse scenario. In this scenario, supply chain disruption reaches levels not seen since the pandemic levels and energy costs rise sharply for a second time since the pandemic.

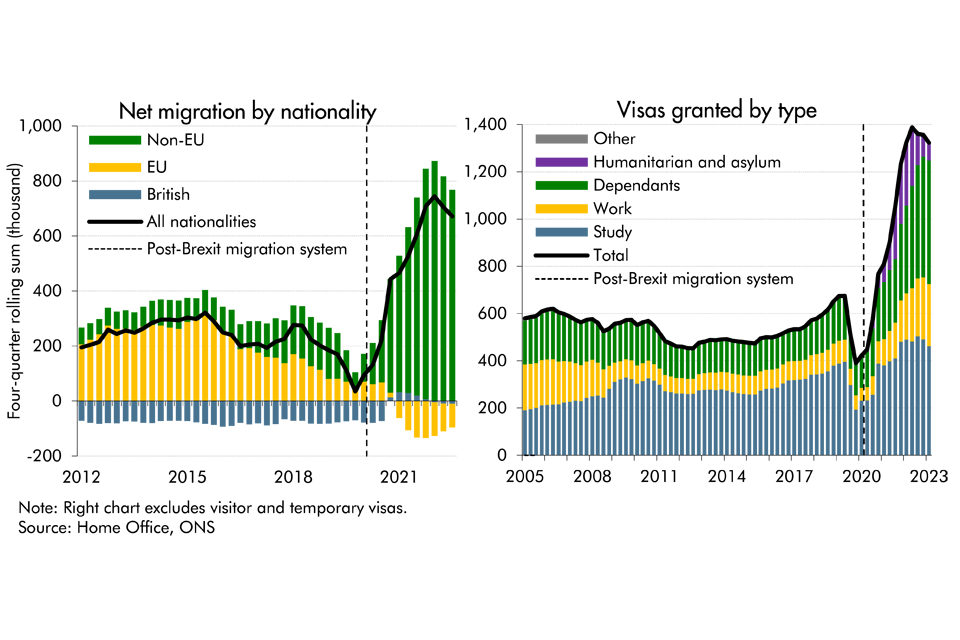

Latest data from the ONS suggest that net migration to the UK was higher than previously thought in recent years, while it's also projected to be higher than previously expected. In this box, we presented our migration forecast and its impact on labour supply. As there is considerable uncertainty around the outlook, we also considered alternative scenarios for net migration and its economic impact.

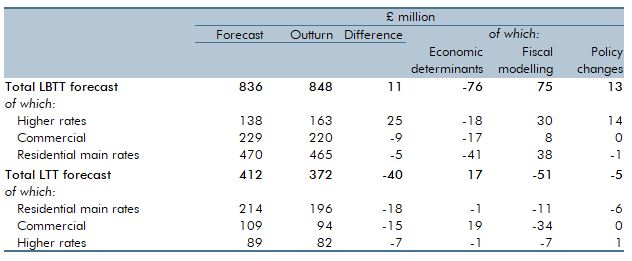

The land and buildings transaction tax (LBTT) was implemented in Scotland on April 1 2015 while the land transactions tax (LTT) began in April 1 2018. Both taxes replaced the UK Government’s stamp duty land tax but operate in similar ways. In this box we evaluated our March 2022 forecasts for 2022-23, and how they compared to the eventual outturn data. We explained the reasons behind the 1.4 per cent surplus for LBTT and the 9.6 per cent shortfall for LTT.

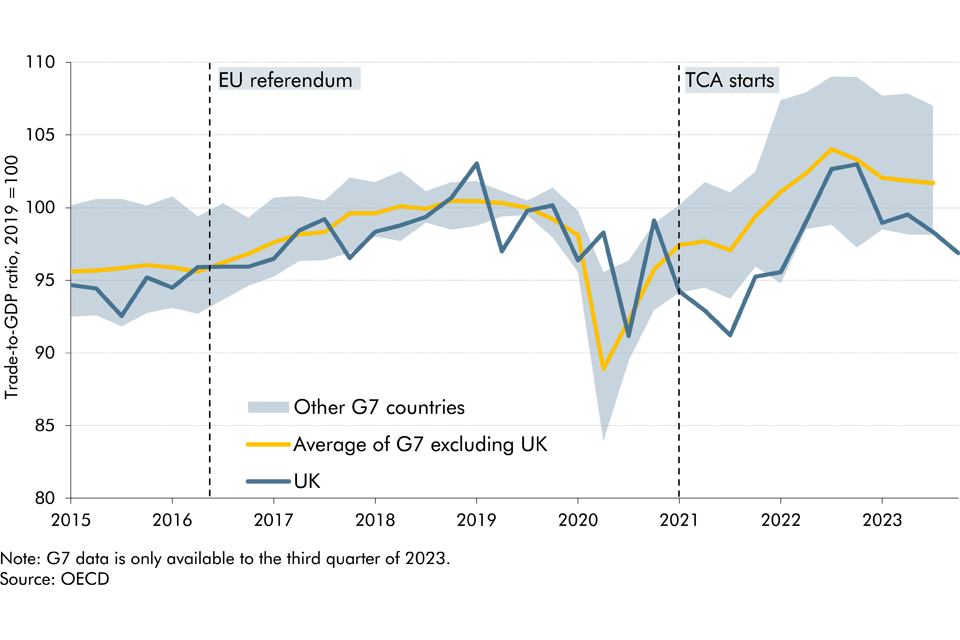

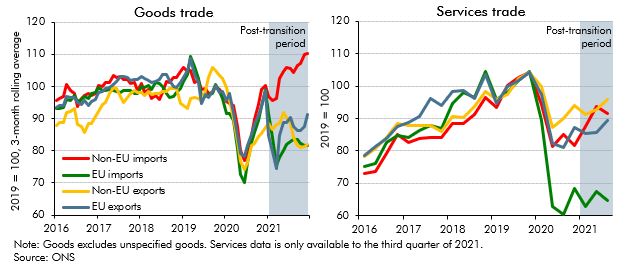

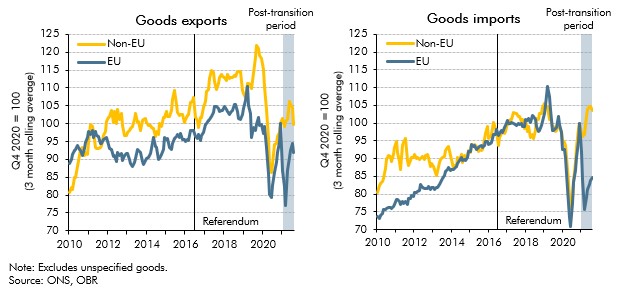

Since the June 2016 EU referendum, our forecasts have incorporated a set of assumptions about the economic impact of Brexit on trade, productivity, investment, and migration. In this box, we assessed our current assumptions on trade against the latest evidence.

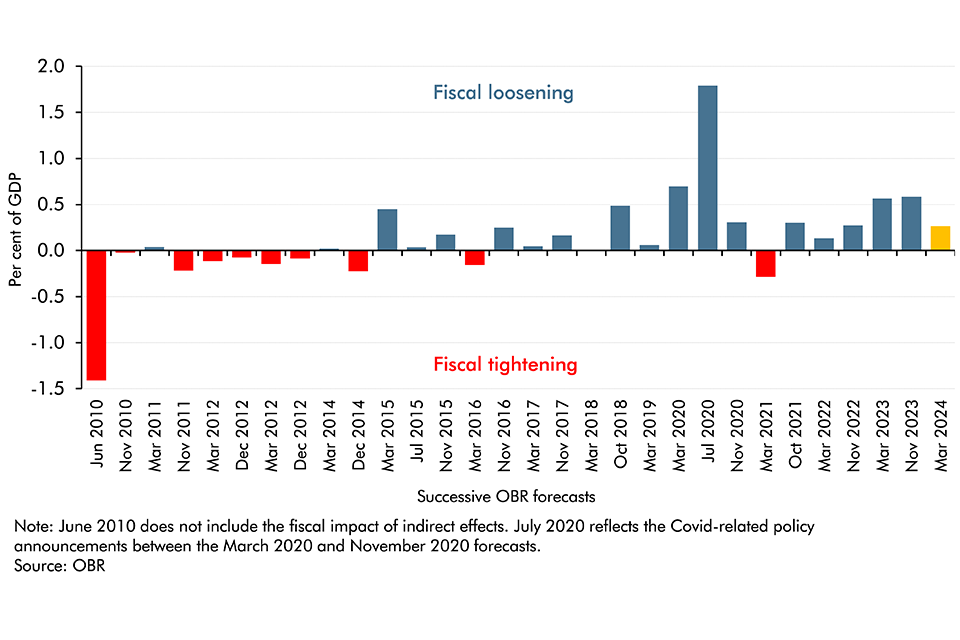

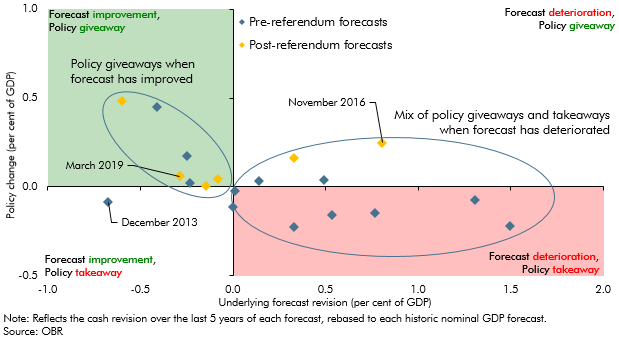

In Budget 2024, the Chancellor has chosen to loosen fiscal policy following the improvement in the underlying fiscal outlook. This continues the consistent pattern of expansionary fiscal policy packages that have been announced in recent years. Since 2010, in every instance of good news on the underlying fiscal position, the policy response has been to spend at least some of the windfall.

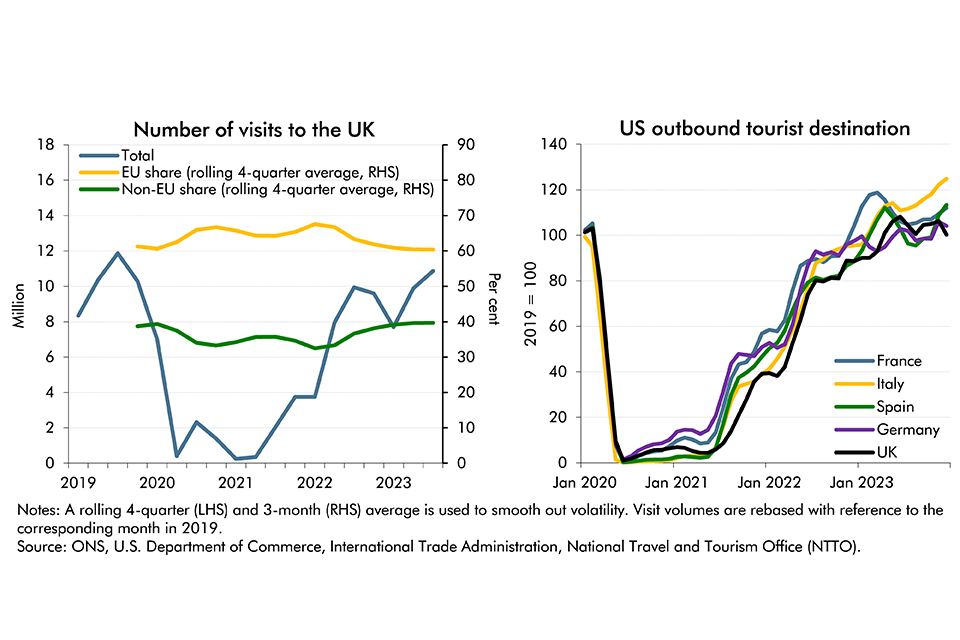

The VAT Retail Export Scheme enabled non-EU visitors to the UK to reclaim the VAT incurred in purchasing goods from participating retailers. It was abolished following the UK’s exit from the EU in January 2021. In reviewing our November 2020 costing in this box, we concluded that its methodology still appears reasonable and that the costing was a central estimate. We updated that estimate to account for the impacts of visitors’ wider spending, but continued to believe that this measure is unlikely to significantly affect the productive capacity of the economy.

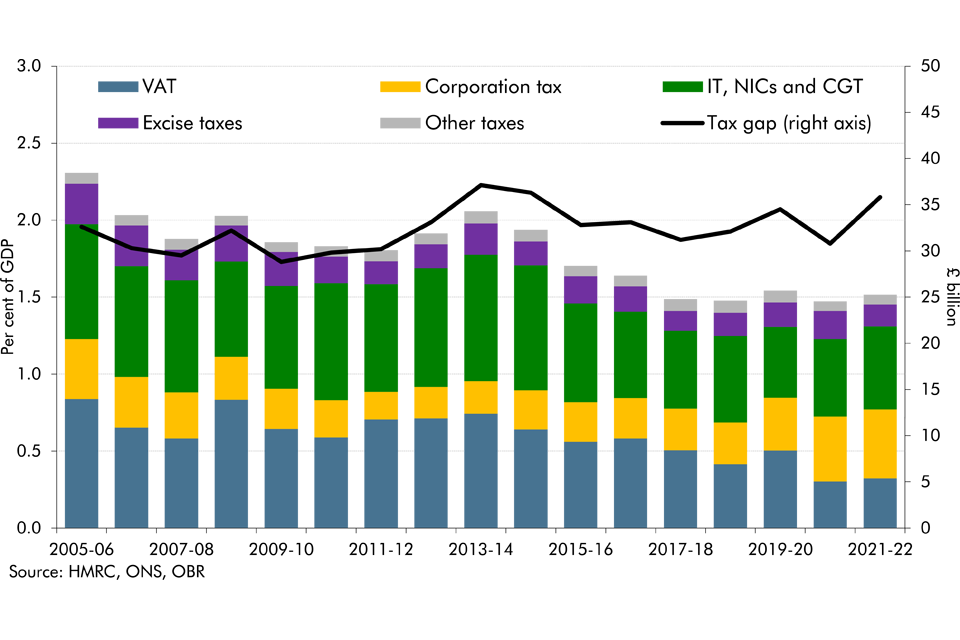

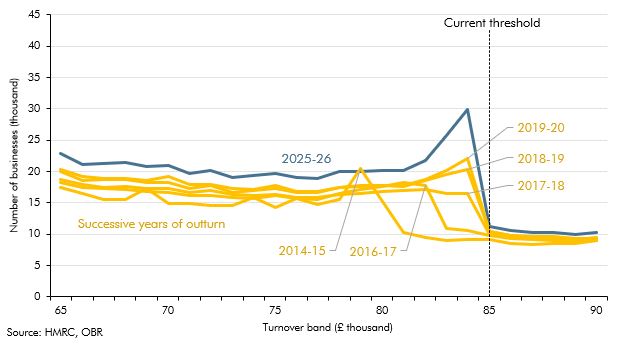

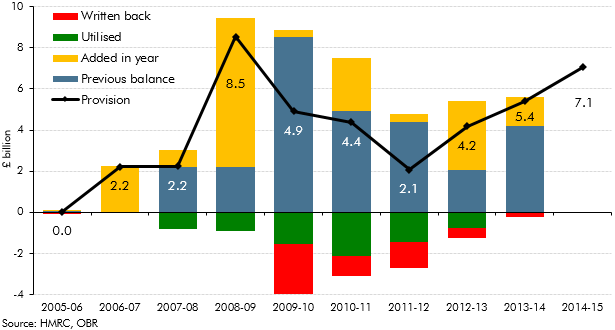

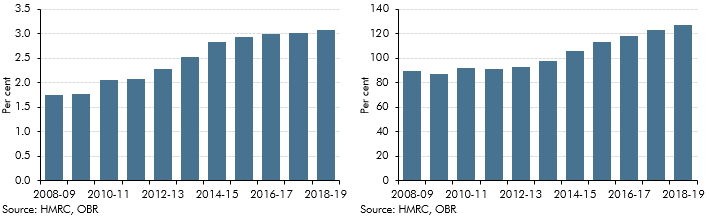

The tax gap is the difference between taxes collected by HMRC and the theoretical liability, or what, in theory, should be collected. As a share of GDP, it has reduced from 2.3 per cent in 2005-06 to 1.5 per cent in 2021-22, two-thirds of which is explained by reductions in the VAT gap. In this box, we explored the recent drivers of changes in tax gaps, explained what assumptions we make about tax gaps in our forecast and outlined the associated uncertainties.

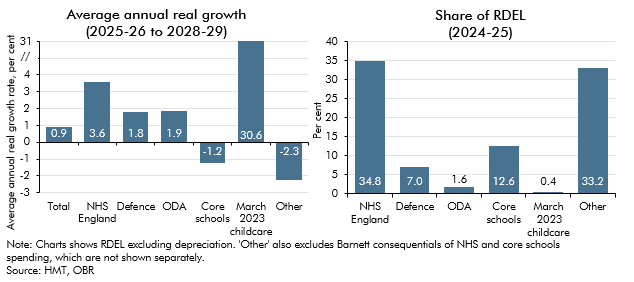

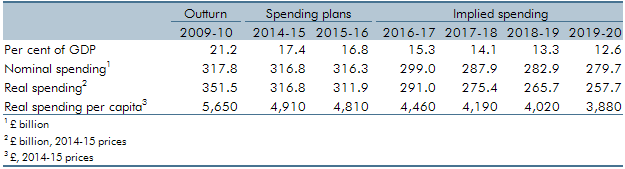

In the final four years of our March 2024 forecast, departmental spending follows an overall envelope set by the Government because the detailed departmental spending plans set at the last Spending Review only extend to March 2025. In this box, we explored the implications of these plans for different departments, and how past governments have revised departmental spending at Spending Reviews.

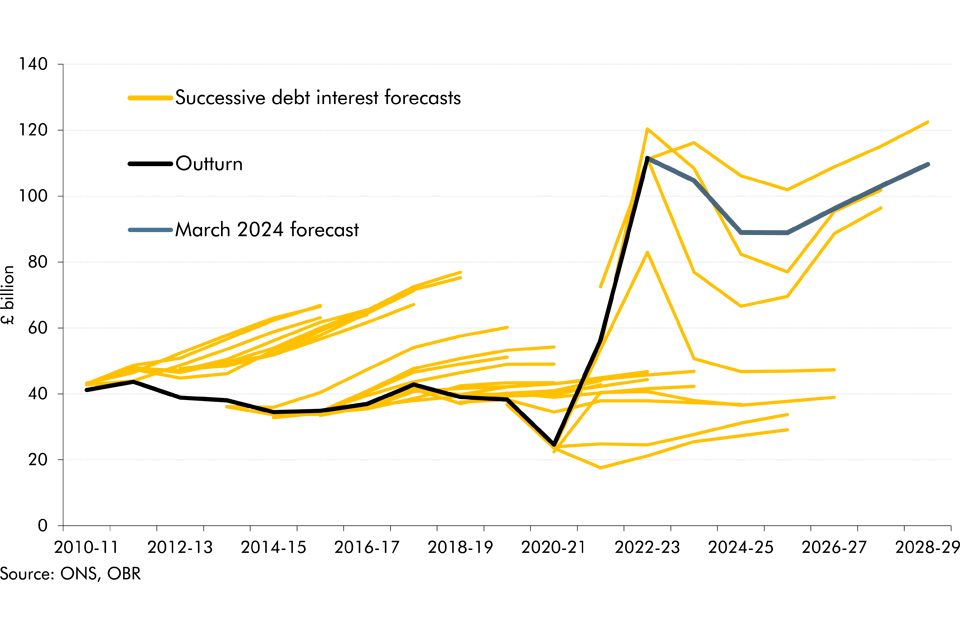

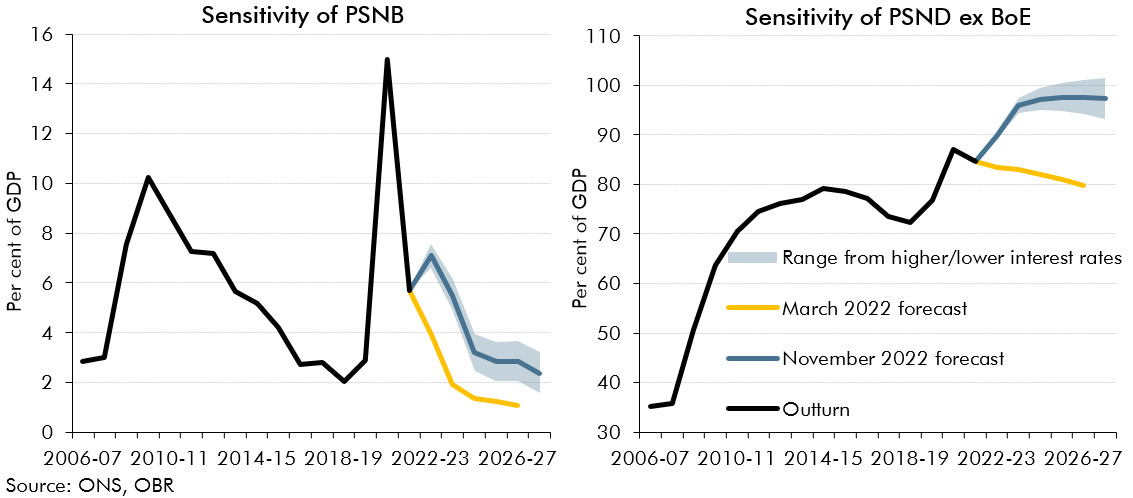

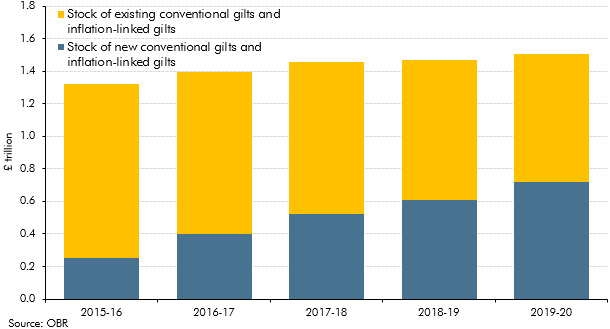

Debt interest spending has reached post-war records as a per cent of revenue and GDP in recent years and has also proved to be incredibly volatile and subject to large revisions between our forecasts. In this box we looked at the reasons for this elevated spending and volatility and how the process of quantitative tightening by the Bank of England will impact the maturity of this debt.

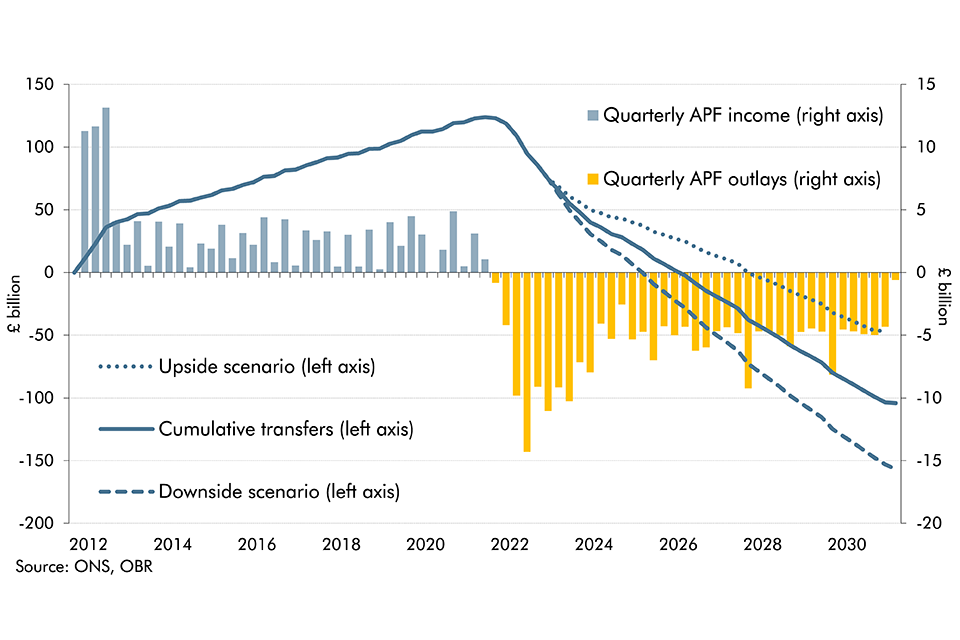

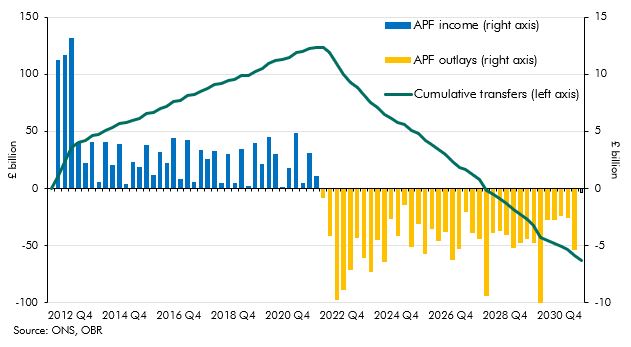

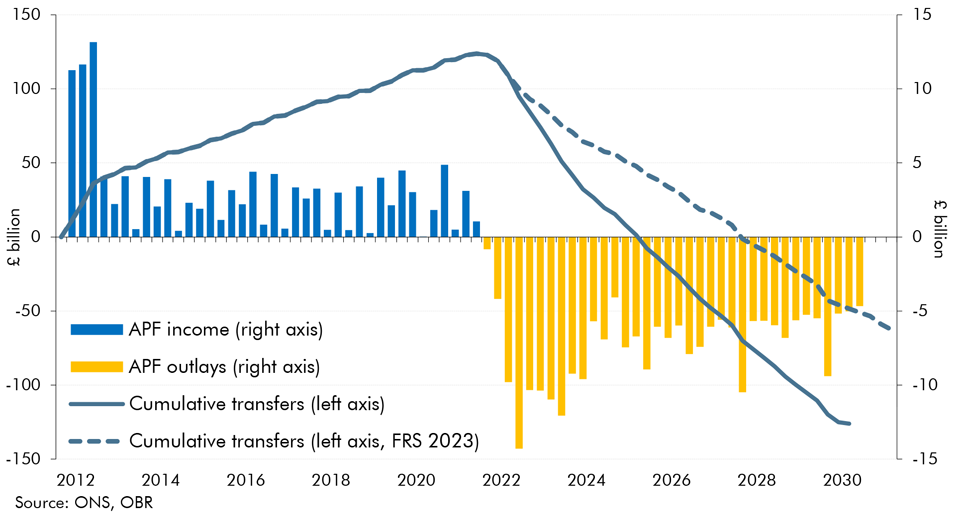

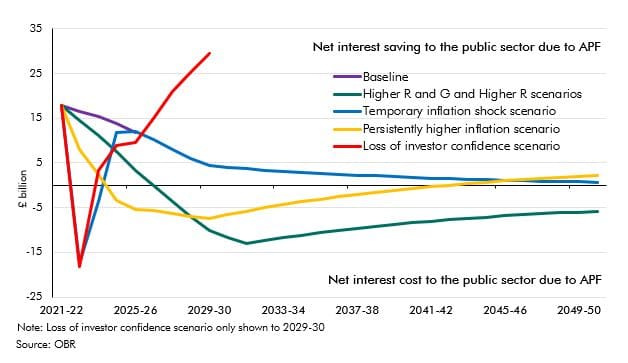

The Bank of England's Asset Purchase Facility (APF) conducts the Bank's operations for quantitative easing and tightening. In this box we updated our estimate of the lifetime direct costs of the APF and scenario analysis looked at the impact of changes in interest rates on this lifetime cost.

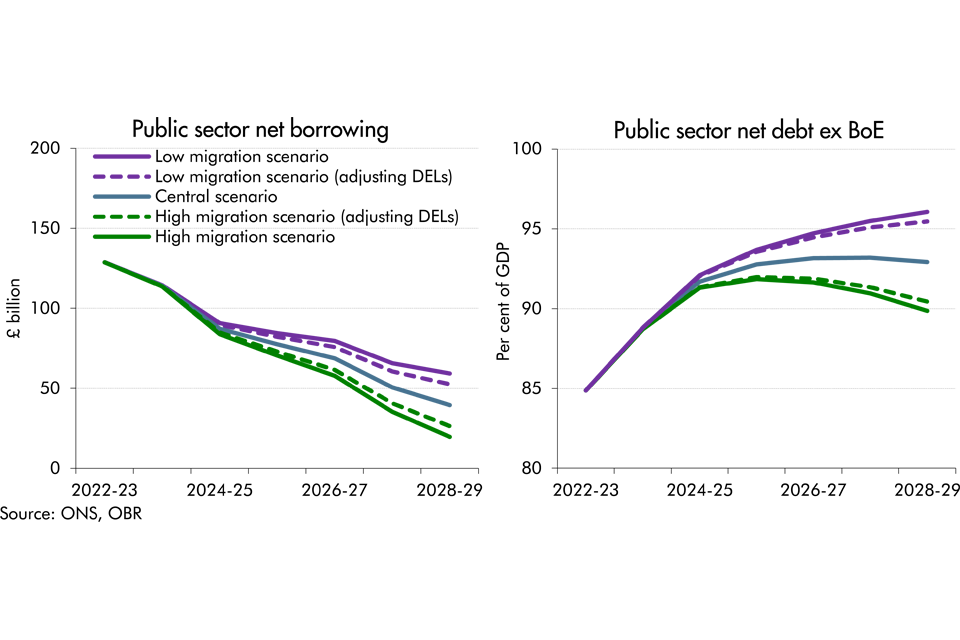

Following the upwards revision to our migration forecast, this box explored the implications of higher migration on our central forecasts for tax revenues, spending and borrowing. We also drew on alternative scenarios for migration to illustrate how uncertainty in the migration forecast translates into the fiscal forecast.

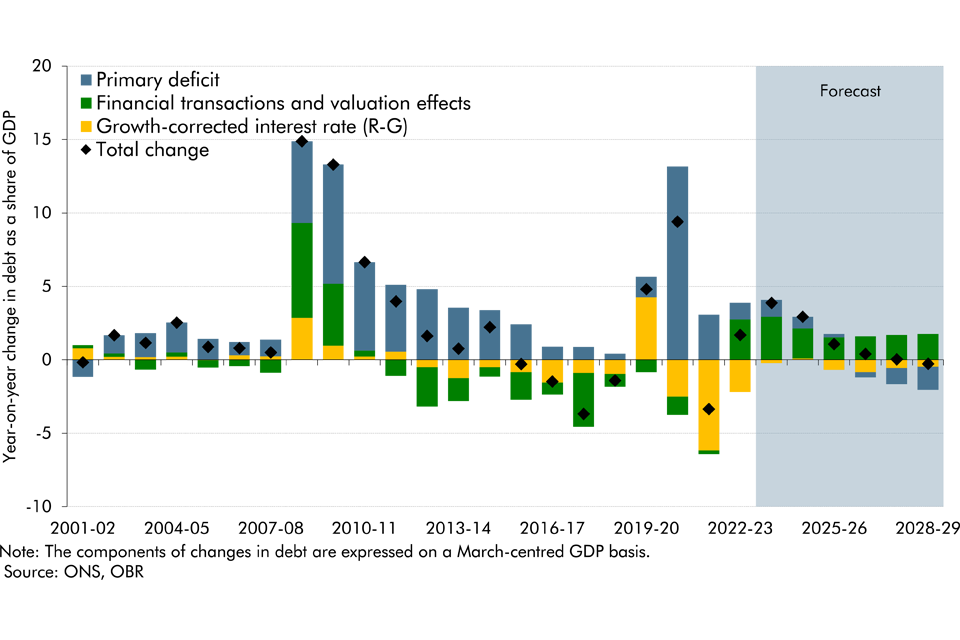

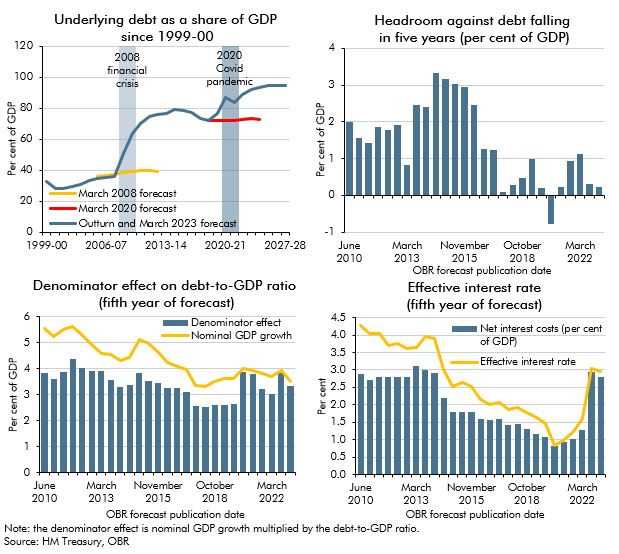

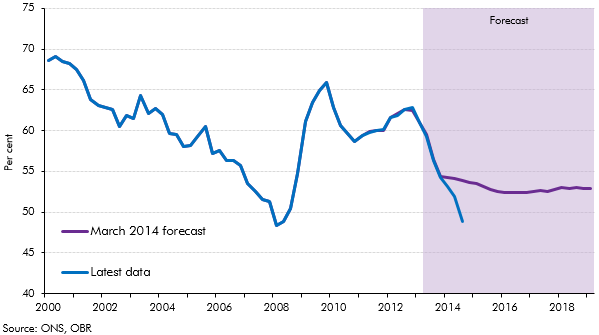

Public sector net debt (excluding the Bank of England) as a share of GDP has tripled since the beginning of this century. This box explored the drivers of the rise and its evolution over the forecast.

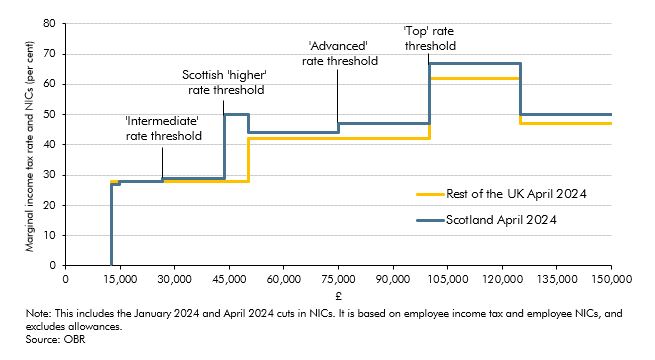

Income tax was devolved to the Scottish Government in 2016 and policy changes since then have led to a divergence with the UK Government’s income tax system. In this box we explored the costing of the Scottish Government’s December 2023 decision to introduce a new 45 per cent ‘advanced’ rate and to raise the ‘top’ rate to 48 per cent, including the potential behavioural responses.

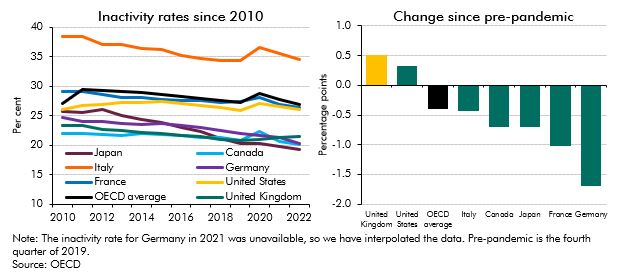

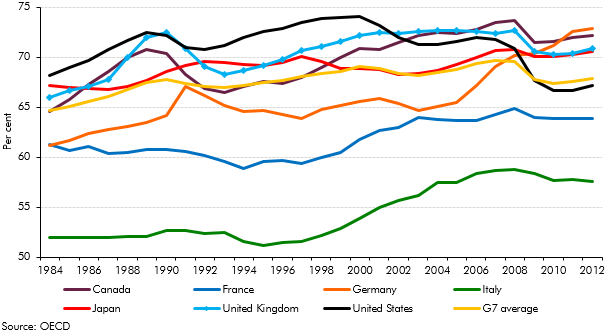

Inactivity fell across the G7 countries in the years prior to the onset of the pandemic and the UK consistently had one of the lowest inactivity rates. Since then inactivity has risen in the UK and US, but fallen across the rest of the G7 countries. This box detailed these changes and looked at ill-health as a driver of inactivity across the G7.

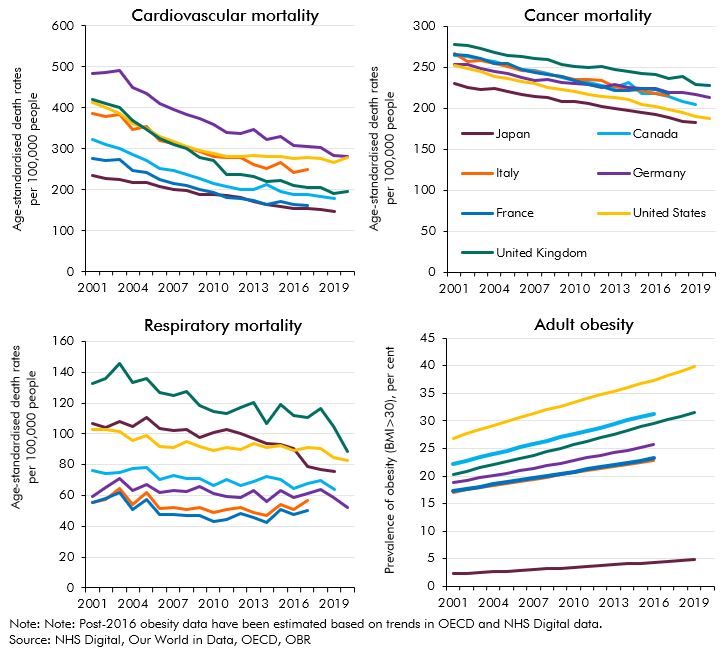

The improvements seen in life expectancy and a variety of other health indicators in the UK over a period of several decades have slowed down and - in some cases - partially reversed. This box detailed these changes and compares them to trends in other G7 countries.

Benefits for working-age claimants with health problems have changed significantly over the last thirty years through the introduction of new benefits and assessments. This box described how the UK welfare system operates for working age claimants with and without health problems, and how this has changed over time.

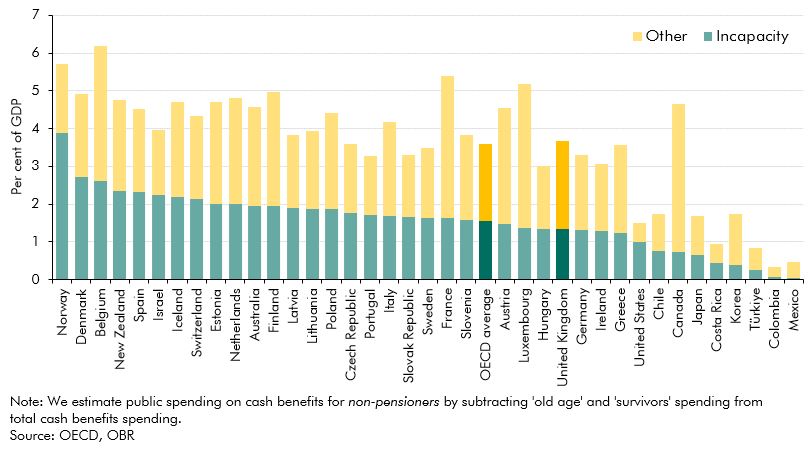

The UK spent close to the OECD average on non-pensioner cash benefits in 2019. This box compared the provision and generosity of health-related welfare across countries, drawing on several international studies.

The referral to elective treatment waiting list in England has risen steadily since the onset of the pandemic, to 7.4 million treatments in April 2023. This box used waiting list and LFS data to estimate the effect on employment and inactivity of halving the waiting list by 2027-28.

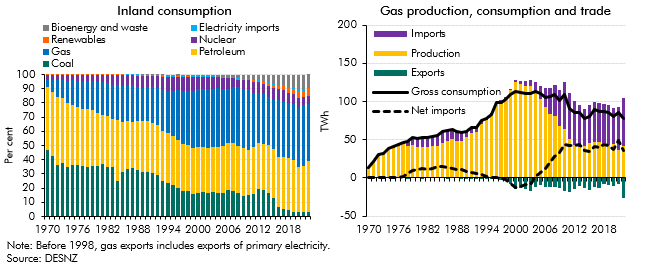

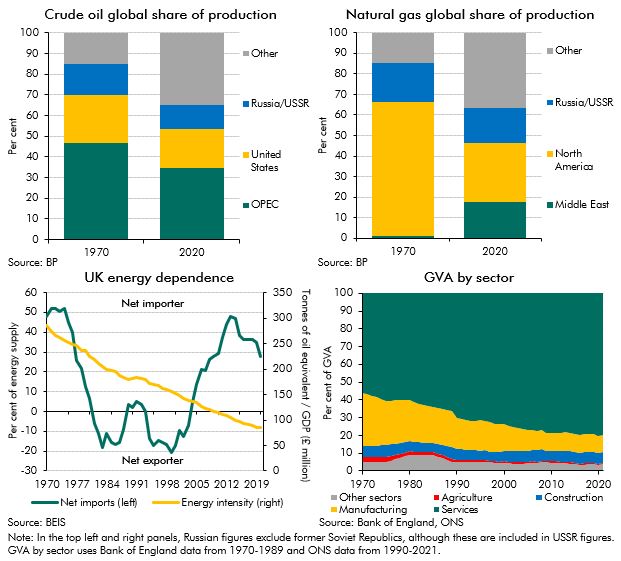

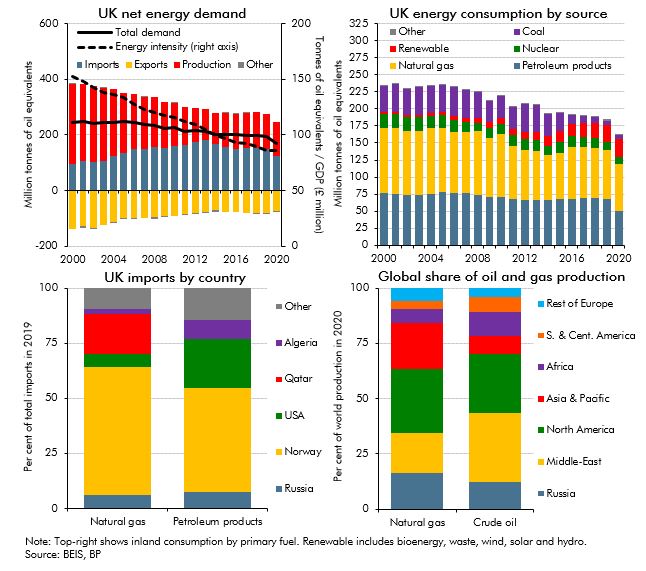

Since 1970 the UK's energy sector has undergone significant shifts following the discovery of oil and gas in the North Sea and the energy shocks of the 1970s. In this box we summarised the historical events and changes that has led to the UK has become increasingly dependent on imported gas.

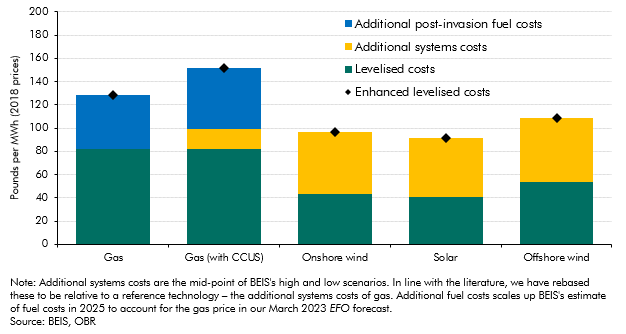

An estimate of the full cost of different energy sources to the power system needs to reflect more than just the construction and operating costs of energy generators that are captured in the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE). In this box we explored enhanced measures of levelised costs of energy.

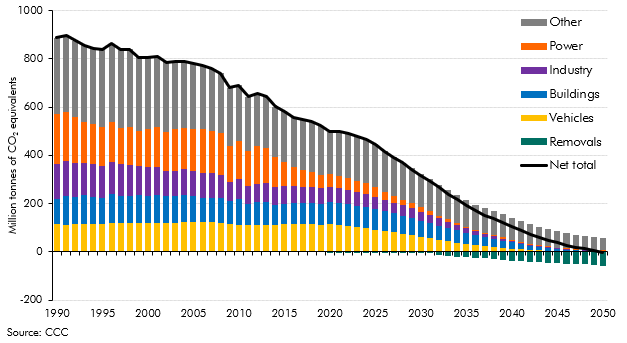

Since our 2021 Fiscal risks report - which showed that reaching net zero carbon emissions will have significant impacts on the public finances in the UK - estimates of the fiscal impacts of reducing emissions in other countries have begun to be produced. In this box we recapped our 2021 work and discussed how IMF and French analysis compared to it.

Up to July 2022 the Bank of England's quantitative easing (QE) activities had made large profits resulting in large transfers to the Treasury but since then flows have reversed. This box described what the whole lifetime direct costs of QE would be based on our March EFO assumptions.

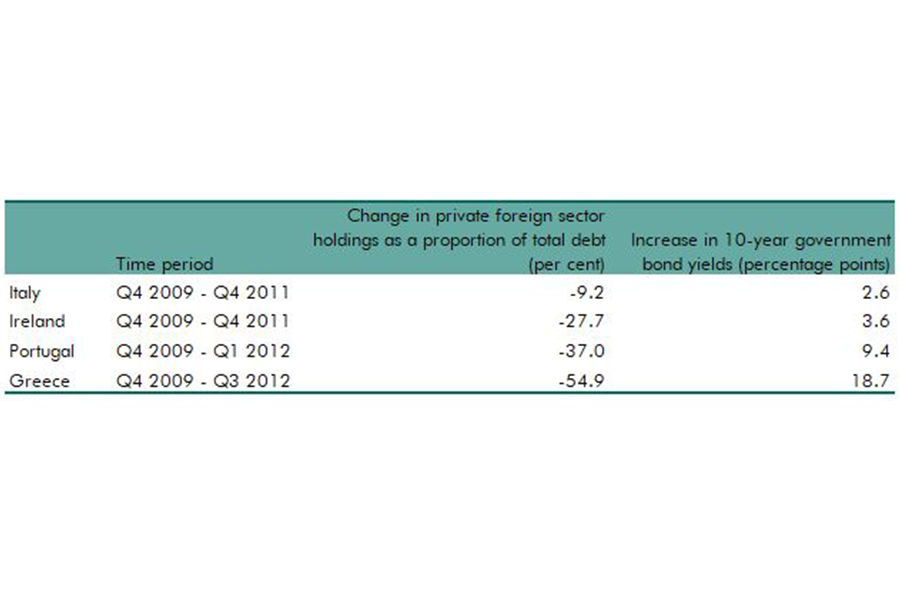

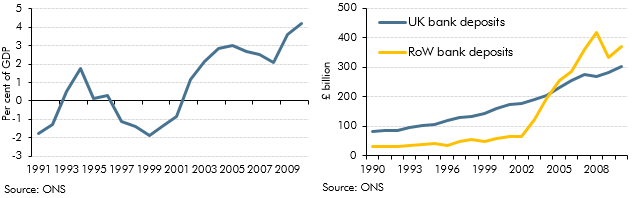

As the stock of foreign holdings of UK debt has risen this century, so have questions about the risks of increasing, relatively high, levels of these holdings. This box looked at the why holdings of debt by foreign investors may lead to greater market volatility.

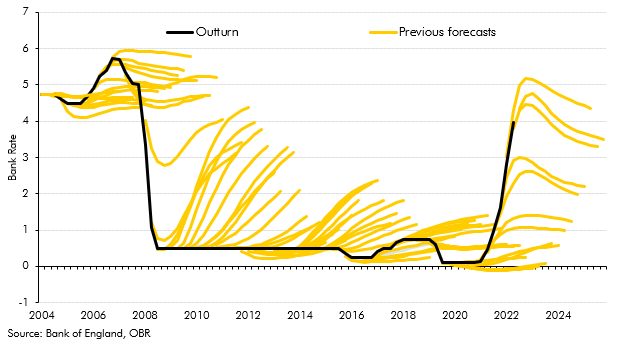

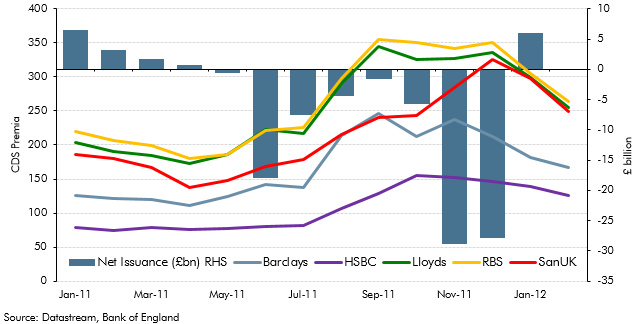

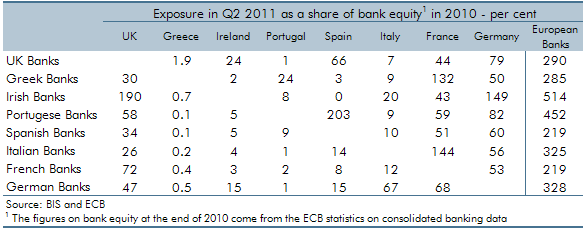

There has been a notable shift in the environment of interest rates over the past 18 months in the UK. This box looked at the extent of surprise for rate rises relative to market implied expectations and the increase in capital adequacy ratios of UK banks since the global financial crisis.

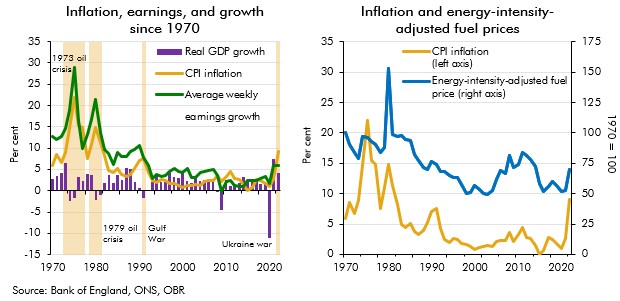

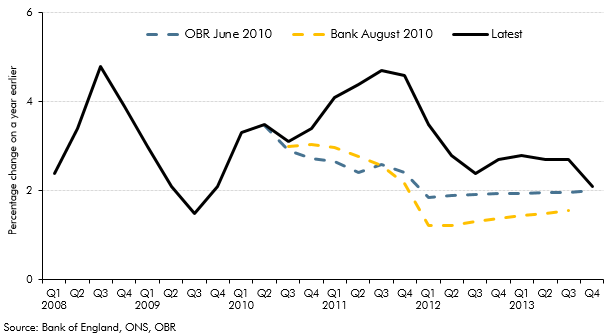

Our recent forecasts have significantly underestimated inflation outturns, with the March 2021 underestimation of inflation in 2022-23 being the largest difference between forecast and outturn since the OBR began forecasting in 2010. In this box we explored the reasons that might have driven these differences since our March 2022 forecast. In particular, we considered the extent to which the knock-on effects of higher energy prices on CPI inflation might have been higher than we originally assumed.

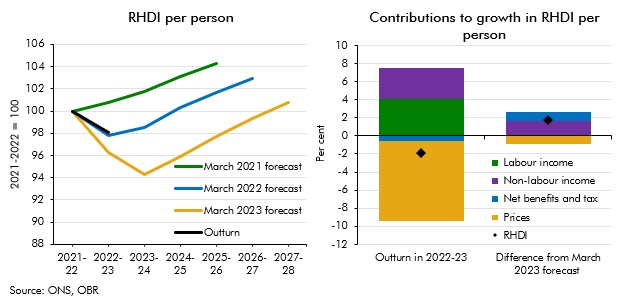

Real household disposable income turned out stronger than our recent forecasts expected for 2022-23. This box explained that differences are largely explained by net benefits and taxes as well as non-labour incomes providing stronger support to living standards than forecast.

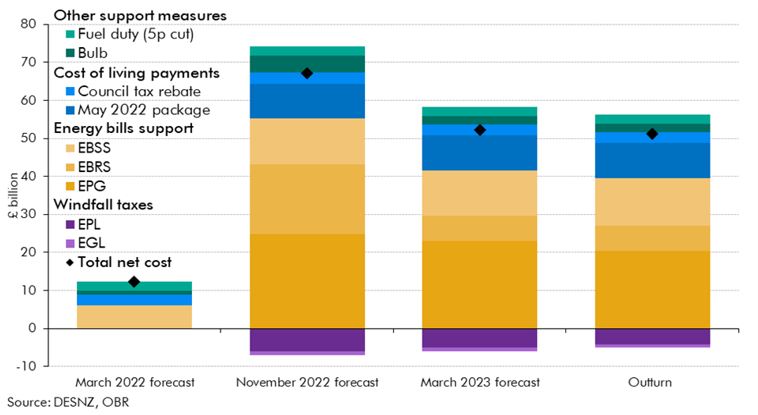

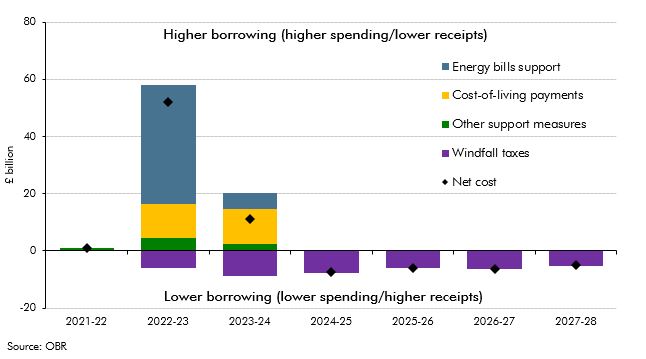

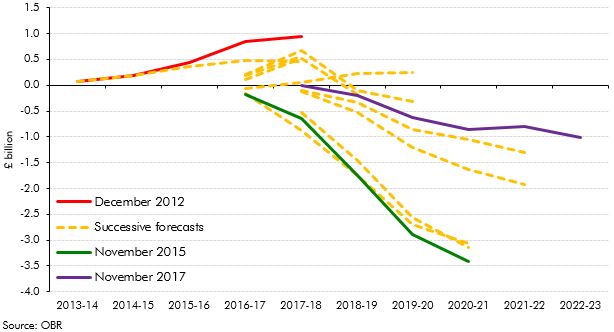

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 led to a surge in wholesale and retail energy prices, and a subsequent rise in inflation to a four-decade high. To support households and businesses, the Government introduced a series of policies during 2022 which were a key factor pushing spending and borrowing outturn in 2022-23 above both our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. This box examines how the costs associated with this policy response in 2022-23 evolved over successive forecasts and in initial outturn.

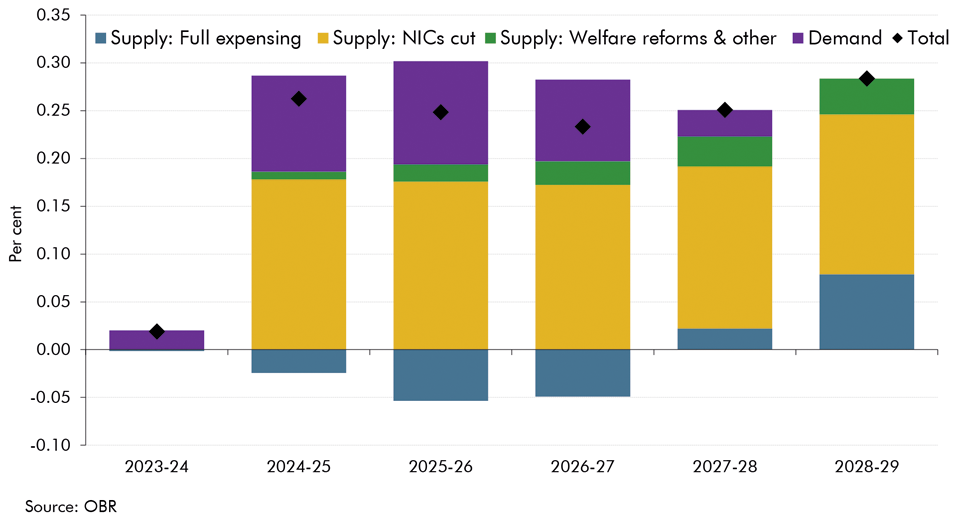

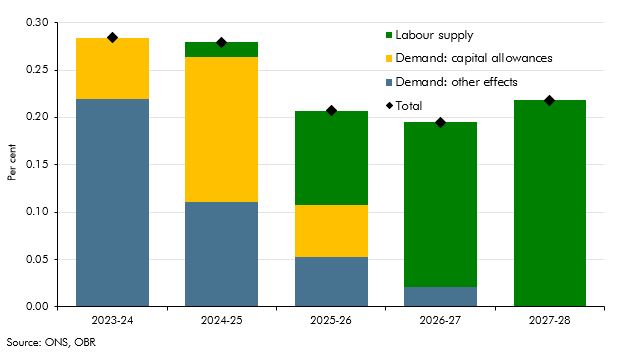

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2023 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our forecast to account for permanent full expensing and fiscal loosening. And, we considered the effects of policy to boost employment on our potential output forecast.

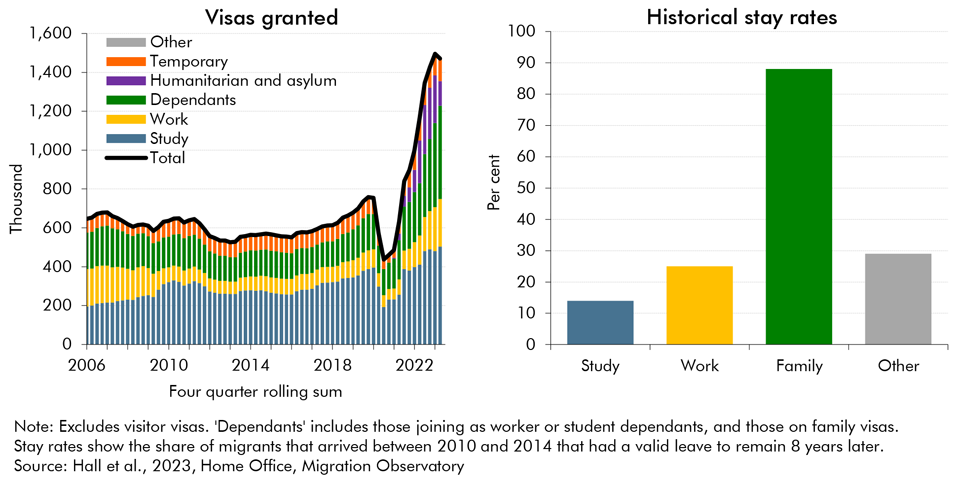

Net migration to the UK increased substantially in recent years but the ONS's population projections, that normally underpin our forecast, did not fully account for that rise at the time. In this box, we explored recent trends in migration and outlined our revised near-term migration forecast. We also examined how likely the migrants were to participate in the labour market.

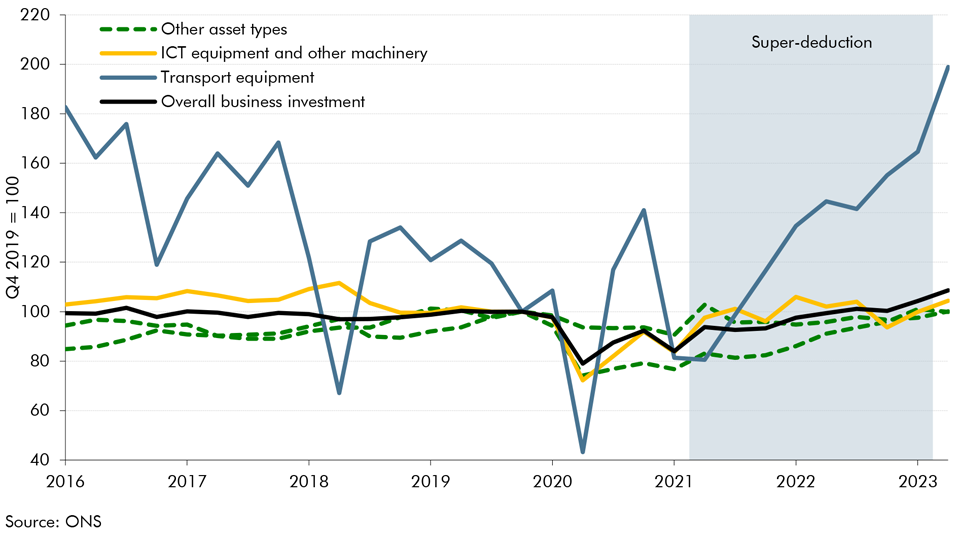

Over the last 3 years, the UK corporation tax system has witnessed four major changes which have consequences on the outlook for business investment. In this box, we explored the effect of the corporation tax rate rise and the super-deduction on investment, before assessing the impact of moving from temporary to permanent full expensing as announced in this Autumn Statement.

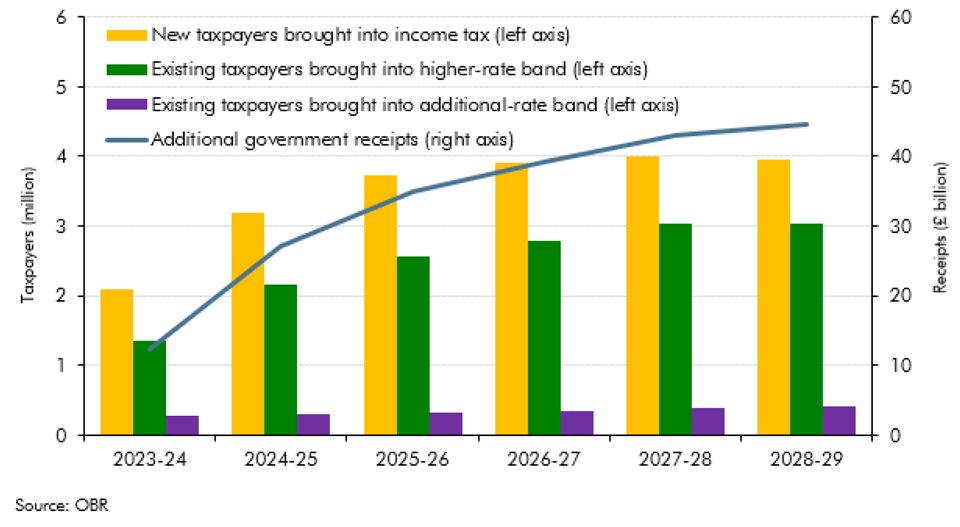

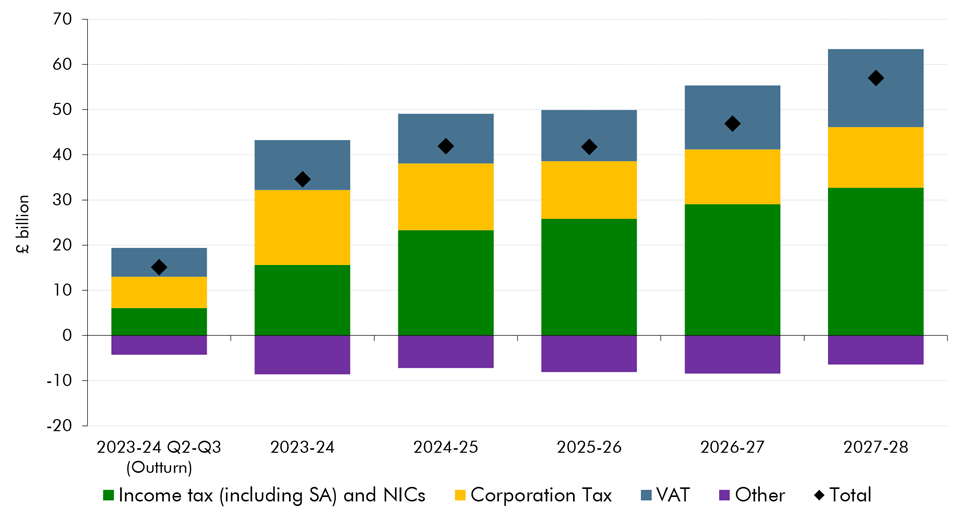

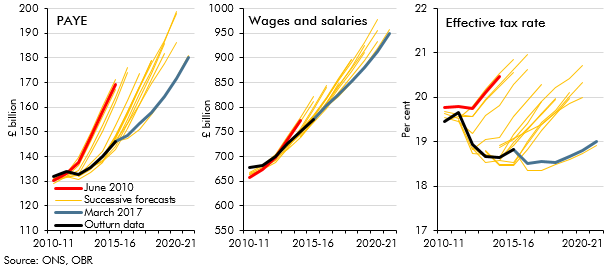

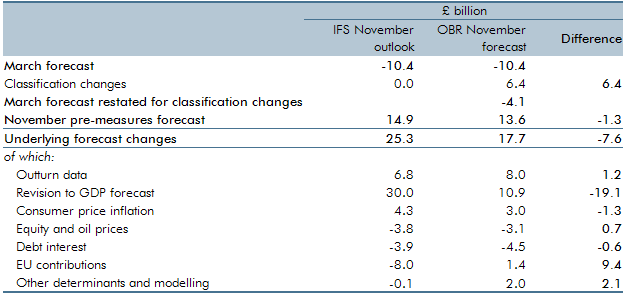

We have made a significant upward revision to our pre-measures receipts forecast. This box explored the drivers behind the revision, which taxes drive the revision and how much of this change is due to real GDP, inflation and the effective tax rate.

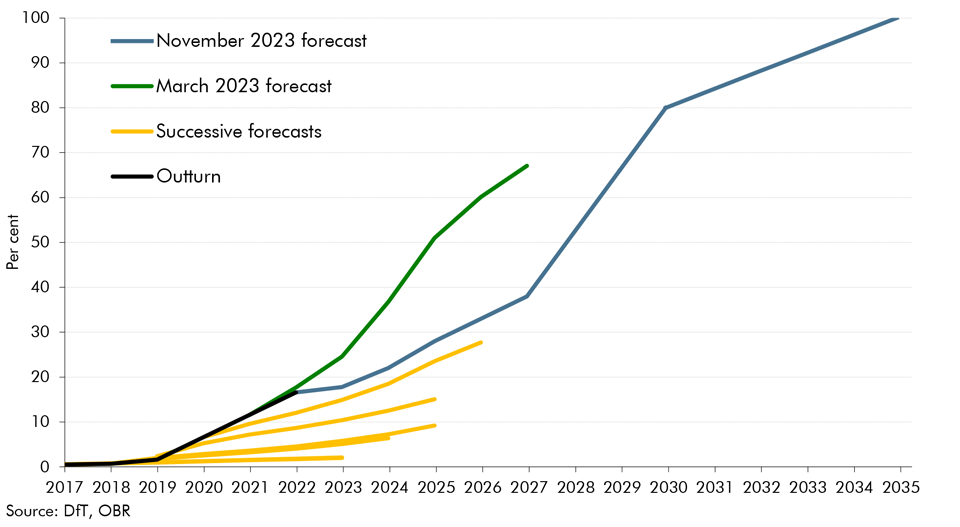

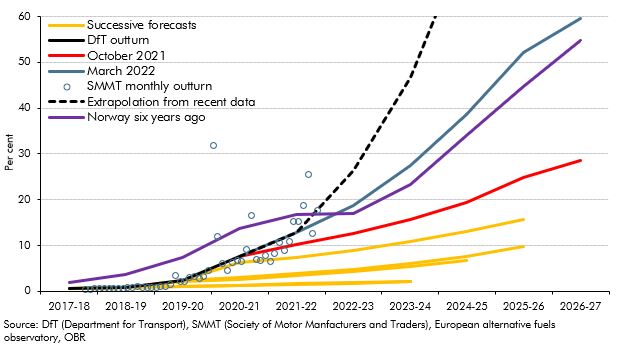

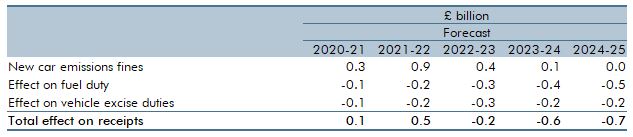

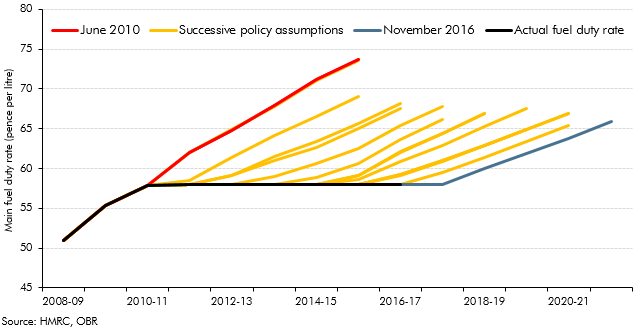

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) has direct fiscal implications for fuel duty revenues (and, to a lesser extent, vehicle excise duty). In this box we explained why we have revised down our EV assumptions and the impact of this revision on fuel duty and VED revenues.

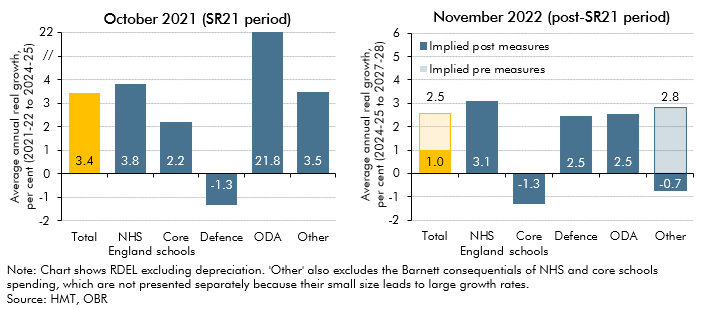

In the final four years of our November 2023 , departmental spending follows an overall envelope set by the Government because the detailed, department-by-department plans set at the last Spending Review only extend to 2024-25. In this box, we explored the implications of these plans for different departments.

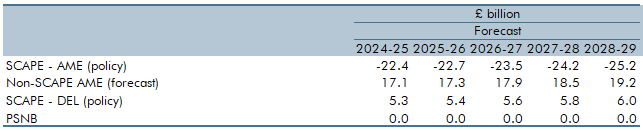

The new SCAPE discount rate, to be implemented in April 2024, increases the present value of future pensions payments and in turn causes employer contributions to rise. Box 4.4 explained the SCAPE rate change and its overall impact on the public finances.

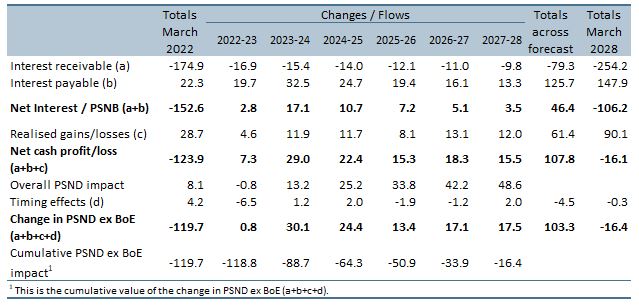

The Bank of England's Asset Purchase Facility (APF) conducts the Bank's operations for quantitative easing and tightening. Since the sharp rise in interest rates in 2022, historic profits from the APF have turned to losses. This box looked at the impact of these losses on fiscal aggregates and the lifetime direct cost of QE.

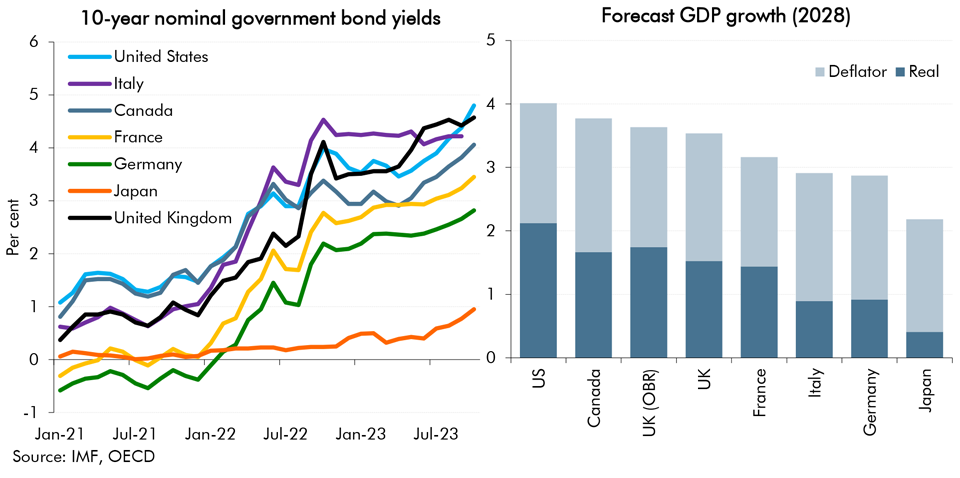

In our November 2023 forecast, alongside higher interest rates, we revised down our estimates for medium term growth. This box explored the challenging fiscal implications of the deterioration in the UK's growth-corrected interest rate, with comparison to other G7 economies.

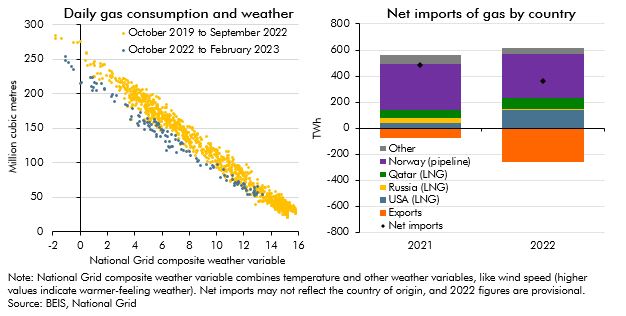

In response to the largest rise in energy prices in around 50 years, an immediate reduction in energy demand, and more gradual change in the composition of energy supply, might be expected. In this box we look at how the sharp rise in the household price of gas has changed households consumption of gas this winter as well as how the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the rise in wholesale gas prices has changed the UK's energy supply over the last year and how it may change further in the future. We then briefly outline how we forecast gas prices and why we do so.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our forecast to account for the loosening of fiscal policy, including a temporary capital allowance. And, we considered the effects of policy to boost employment on our potential output forecast.

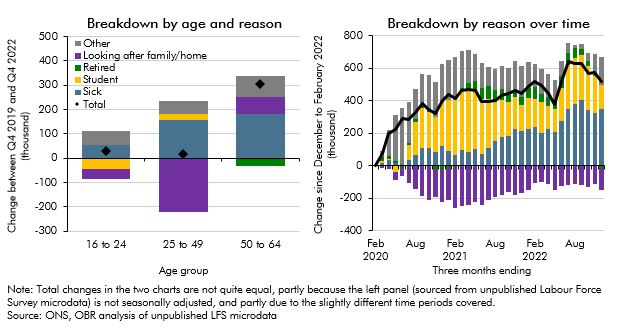

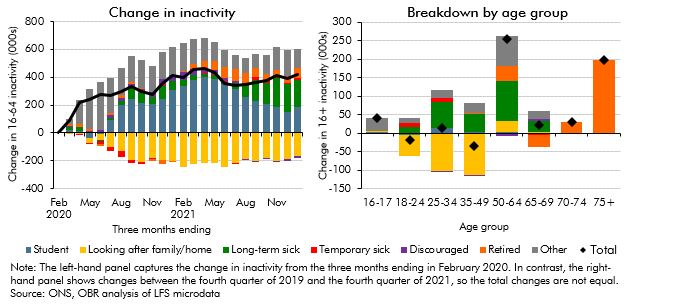

Economic inactivity rose significantly following the pandemic. This box explored the factors behind this rise, including decomposing it into different age brackets and considering the reasons behind it, as well as analysing the flows into and out of inactivity.

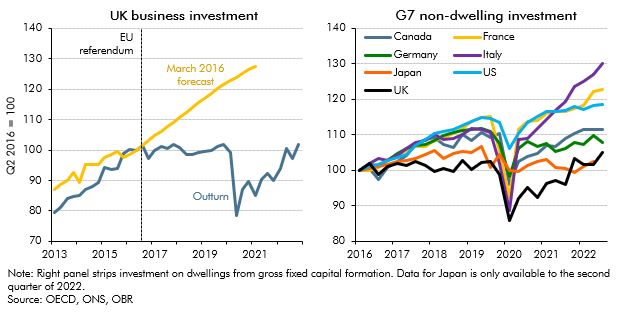

Since the June 2016 EU referendum, our forecasts have incorporated a set of assumptions about the economic impact of Brexit on trade, productivity, investment, and migration. In this box, we assessed our current assumptions against the latest evidence.

In the March 2023 EFO we estimated that the policy package in response to the rise in energy prices would cost £78 billion in 2022-23 and 2023-24. This box assessed how the cost of the UK Government's response compares internationally.

In November 2021 the Government appointed administrators for Bulb Energy Limited and provided facilities to cover Bulb's financing needs. This box described how we accounted for transactions with Bulb in our March 2023 forecast.

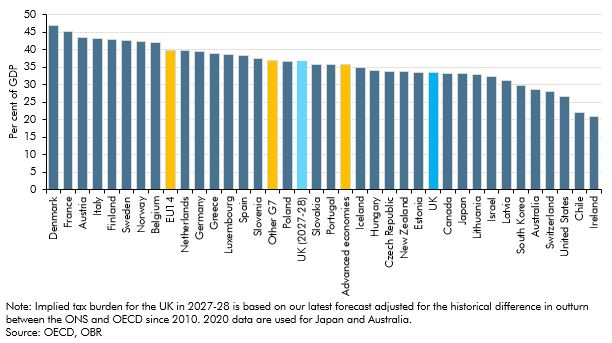

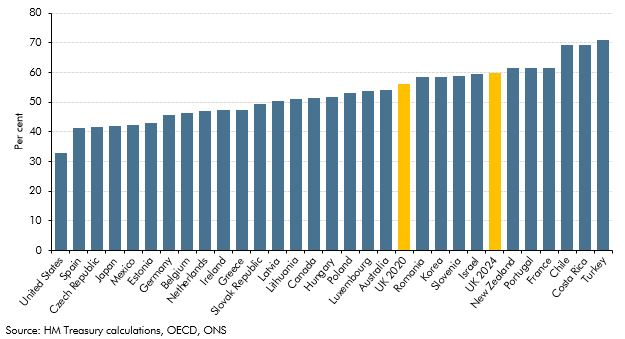

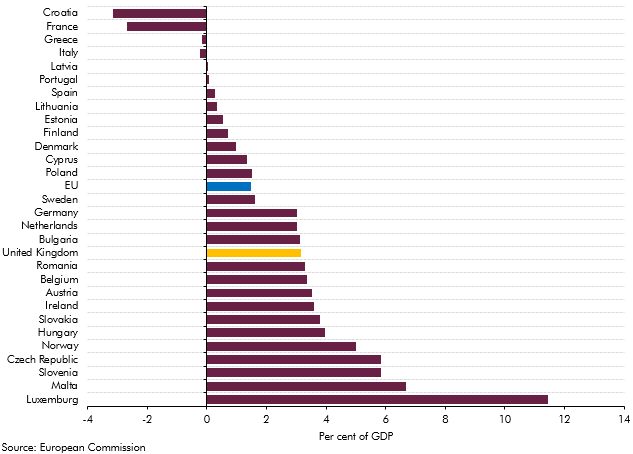

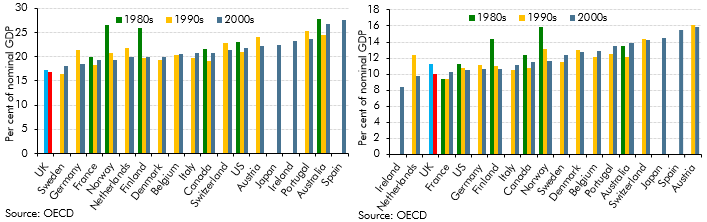

In our March 2023 Economic and fiscal outlook, we forecast that the UK's tax burden was set to rise to a post-war high. This box considered the UK's tax burden in international and historical context.

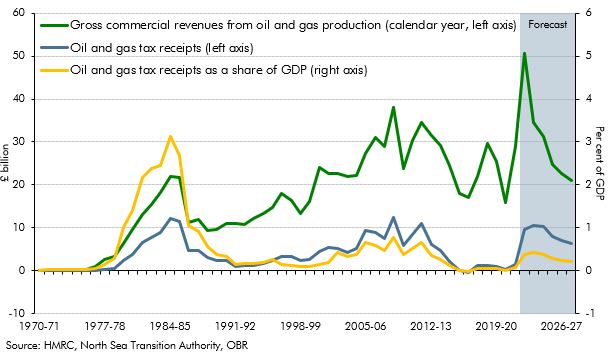

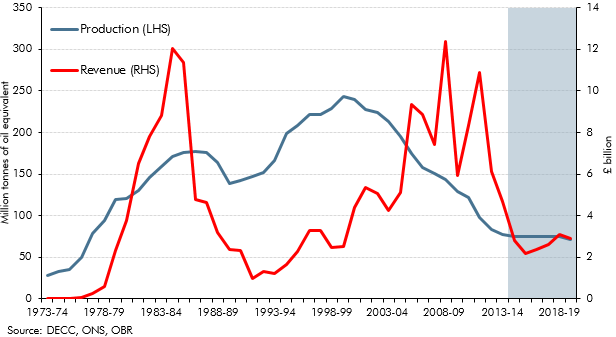

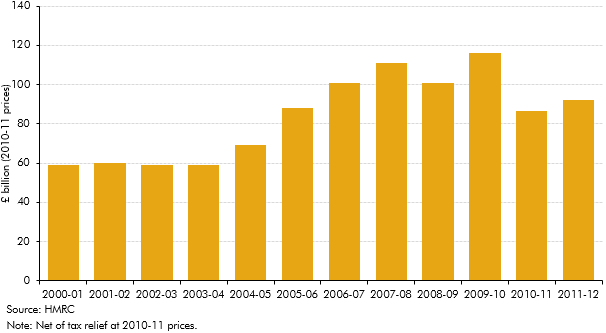

In our March 2023 Economic and fiscal outlook, we forecast that North Sea oil and gas receipts would rise sharply in the near-term to close to their all-time high in cash terms. This box explored the evolution of receipts since the discovery of North Sea oil and gas.

The Bank of England's Asset Purchase Facility (APF) conducts the Bank's operations for quantitative easing and tightening. Following sharp rises in interest rates in 2022 the APF has started to make large cash losses. This box looked at the causes of those losses and how they feed through to fiscal aggregates.

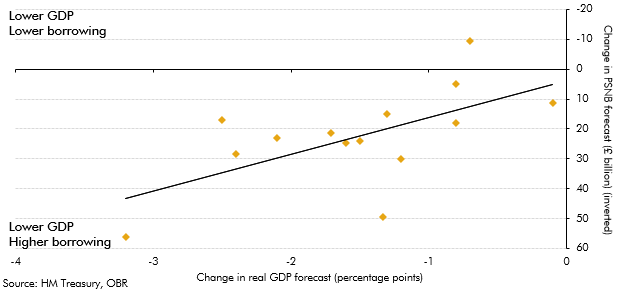

Since the financial crisis successive Chancellors have aimed to reduce debt as a share of GDP. This box looked at why that goal had proved difficult to achieve and in particular the challenges in our most recent forecasts.

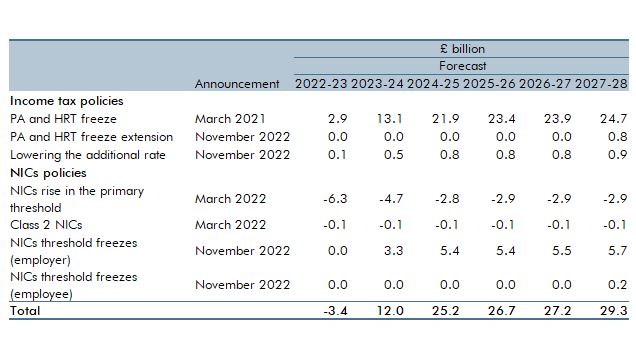

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast to take into account plans for the energy price guarantee (EPG) and consider the impact of tax and spending measures on the supply side of the economy.

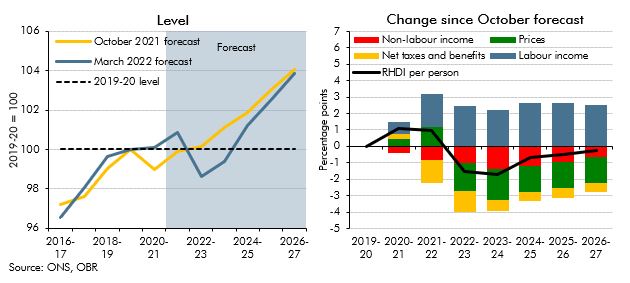

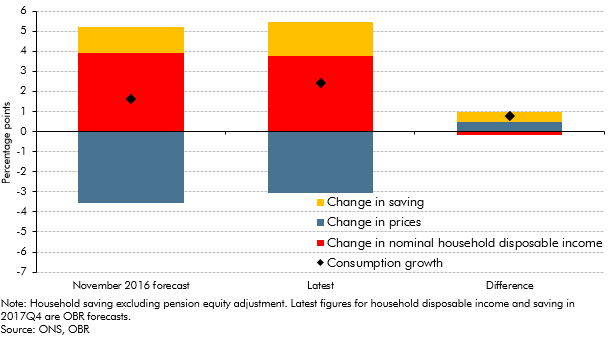

In 2022-23 and 2023-24, living standards are set for the largest fall on record. This box set out our forecast for real household income, the impact of government policy in buffering the income shock, and its implications for our consumption forecast.

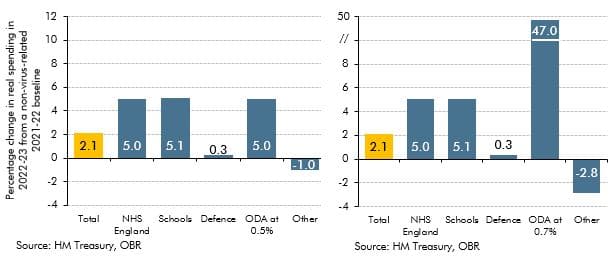

In November 2022 the government reduced its departmental (DEL) spending assumptions for the final three years of the forecast period. This box discussed the implications of the government's day-to-day and capital spending plans for various departments and public services during and after the 2021 Spending Review.

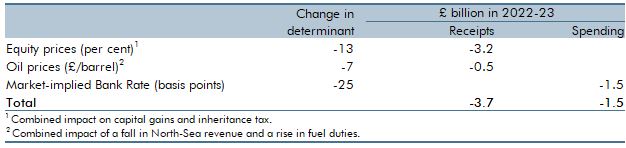

In 2022-23 we have seen sharp rises in gas prices and interest rates, both of which are forecast to remain elevated in 2023-24. This box presented the potential fiscal impacts of a higher-than forecast path for gas prices and two scenarios where Bank Rate is either a percentage point higher or lower than in our central forecast.

The possibility of a new vaccine-escaping Coronavirus variant cannot be ruled out. In this box we explored the possibility of such an escape and investigated the potential economic and fiscal consequences.

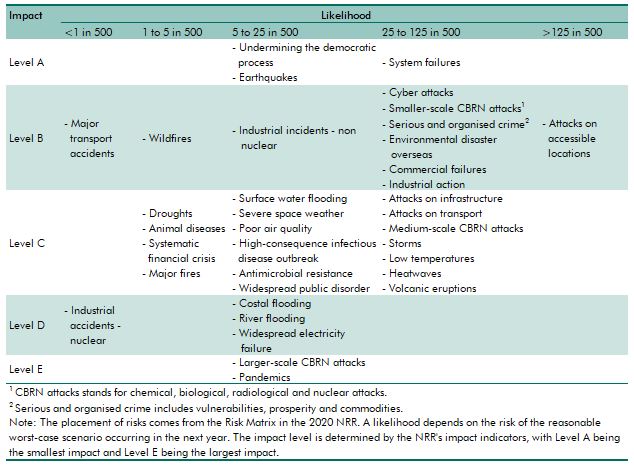

The National Risk Register (NRR) provides the Government's assessment of the likelihood and potential impacts of a range of risks to the safety and security of the UK. In this box box we compared the topics covered by the NRR and those we have focussed on in our risk analysis.

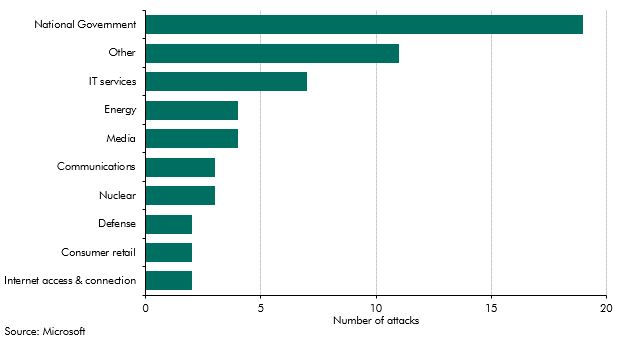

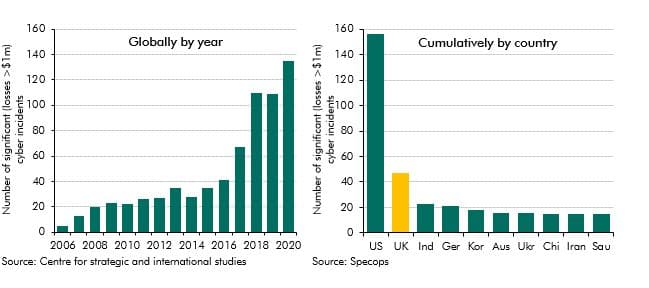

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 led to questions over the impact that cyber attacks were likely to have during the conflict. This box looked at the history of cyber-related activity in the region, and the evidence available for cyber impacts of the conflict to date.

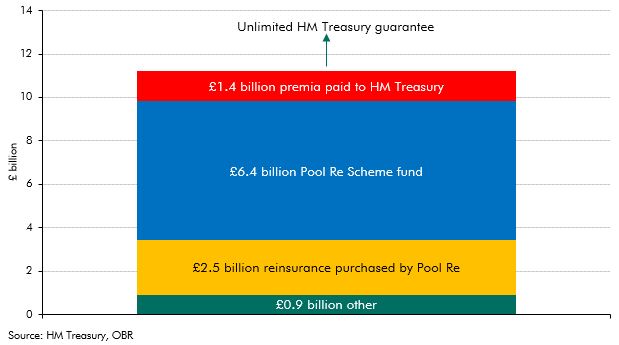

Given signs of pressure in the cyber insurance market, this box considered previous precedent of government intervention to help private insurers provide cover for large and uncertain risks. This included a detailed look at Pool Re, one of the longest running government-guaranteed reinsurance schemes, for terrorism risk.

There are signs that global economic integration has stalled in recent years on some measures and reversed on others. This box discussed the implications of integration for the economy and public finances.

The recent surge in energy prices and its associated effects on inflation has led to comparisons with the last major global energy crisis in the 1970s. This box examined the ways in which the shocks are similar and how they are different, with a focus on how the UK economy in some ways has become more resistent to energy price shocks.

Persistently higher energy prices can reduce the supply capacity of the economy. In this box, we use a production function to estimate the impact of higher fossil fuel prices on potential output.

In May 2022, the Government announced a package of measures to support households with the cost of living. In this box, we explained how we had adjusted our March 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook forecast for these policies.

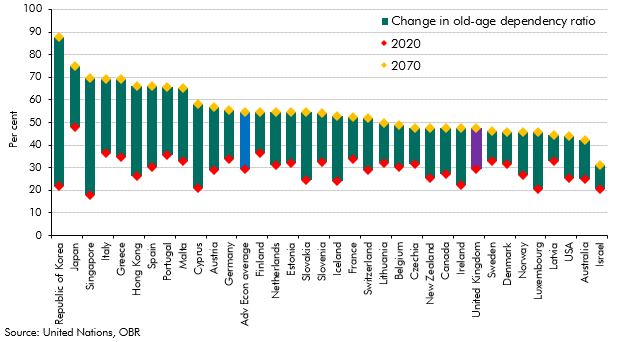

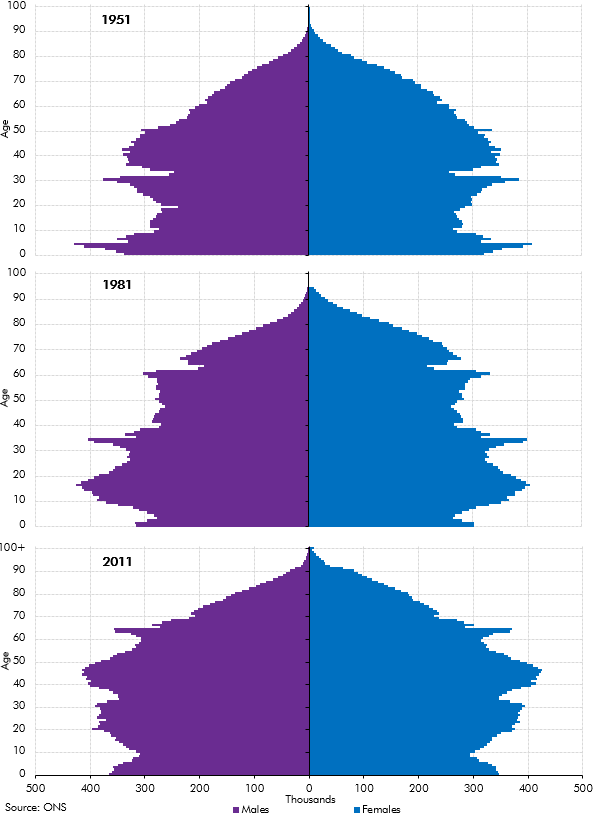

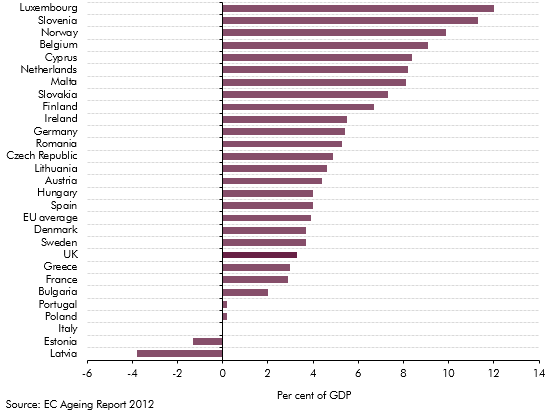

The populations of most advanced economies are ageing, placing new demands on these countries' public finances. This box explored why the UK population is forecast to age slower than most advanced economies over the next fifty years.

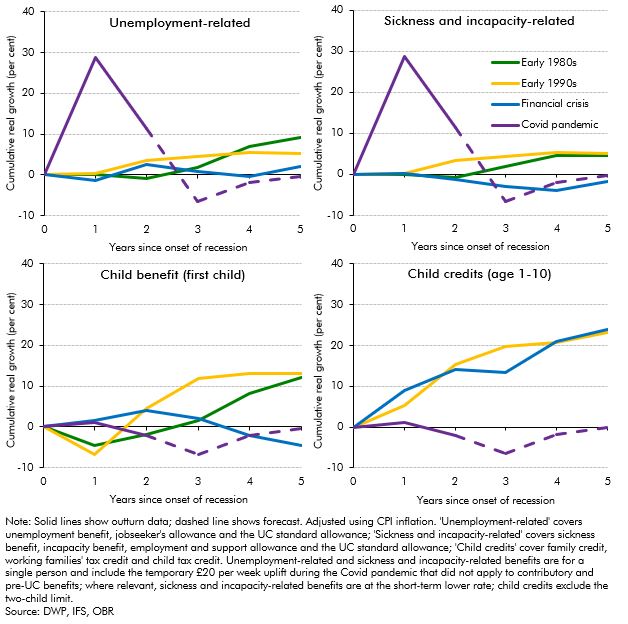

The real-terms value of benefits was forecast to fall by around 5 per cent in 2022-23 (£12 billion in total) before catching up the year after, largely due to the significant rise in inflation and the lag in benefit uprating. In this box we compared these post-pandemic uprating dynamics to the real value of non-pensioner benefit rates following the previous three recessions. This showed that the forecast trough in the real value of benefits was deeper in the wake of the pandemic than for any of the previous three recessions.

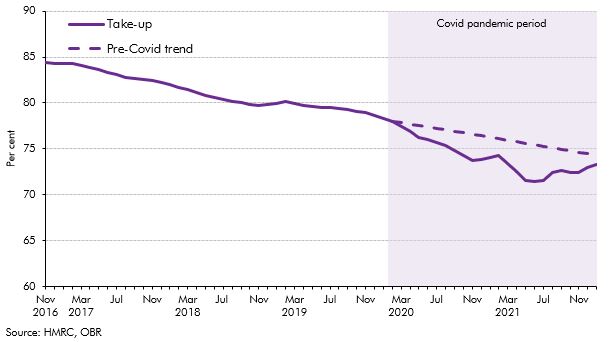

Take-up of child benefit had been declining since 2012-13, but this downwards trend accelerated at the onset of the Covid pandemic in March 2020, which resulted in a steep decline in take-up over the subsequent 18 months. In this box, we considered the main drivers of the child benefit caseload and the effect the pandemic had on each of them. We set out the reasons why the pandemic contributed to lower take-up, and then considered the medium-term impact of the pandemic-driven drop in take-up on our forecast.

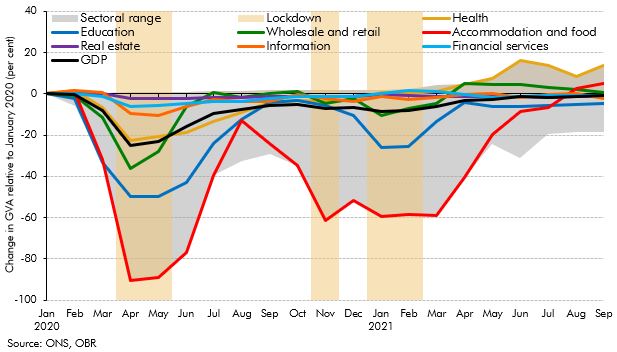

One of the unique features of the coronavirus shock was its extraordinary degree of sectoral differentiation. In this box, we explored the accuracy of our sectoral forecasts and considered the key drivers of forecast errors.

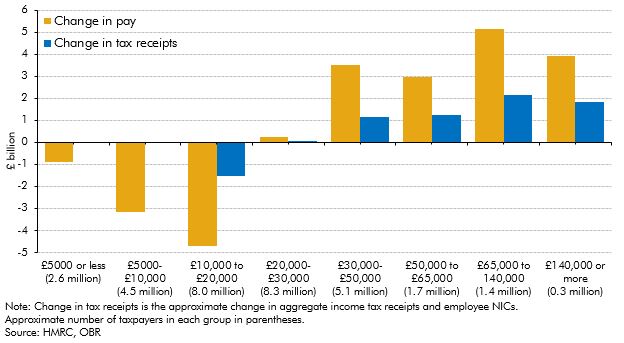

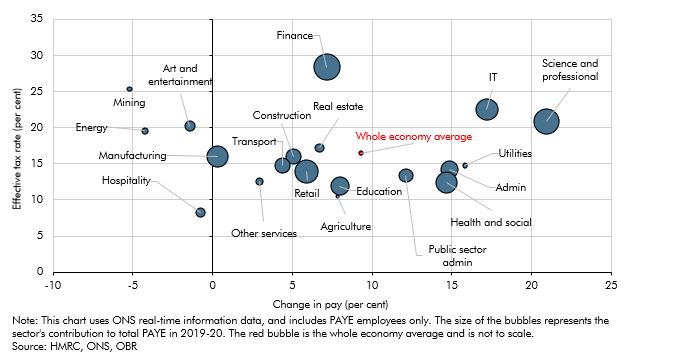

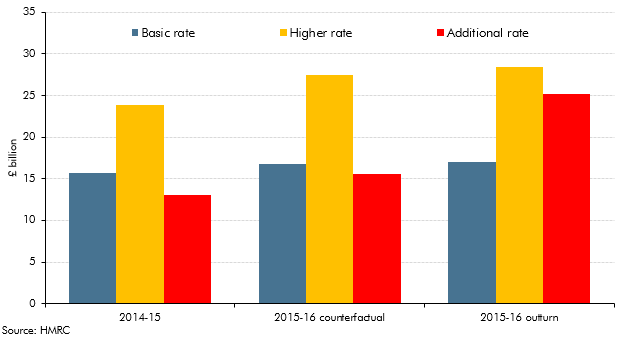

The impact of the pandemic and the national lockdowns has not been equal across the earnings distribution. While it was expected that income tax receipts would be significantly impacted, this box showed that the growth in receipts from higher earners has more than outweighed the fall in receipts from the lowest earners.

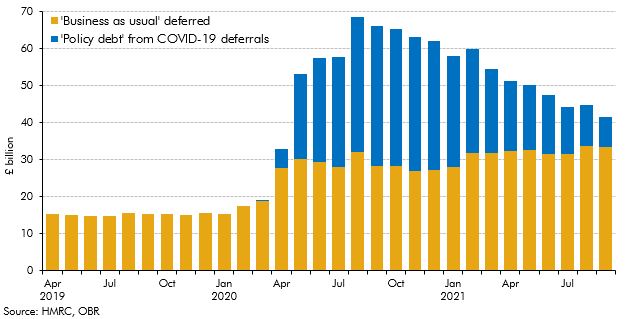

The Government introduced several tax deferral policies in response to the pandemic in an attempt to mitigate the strain on businesses. This box provided an update of the impact of those policies, and the level of tax debt still owed.

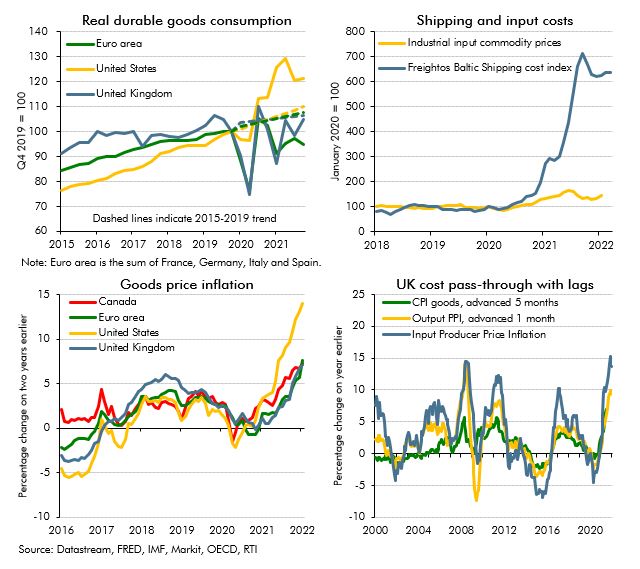

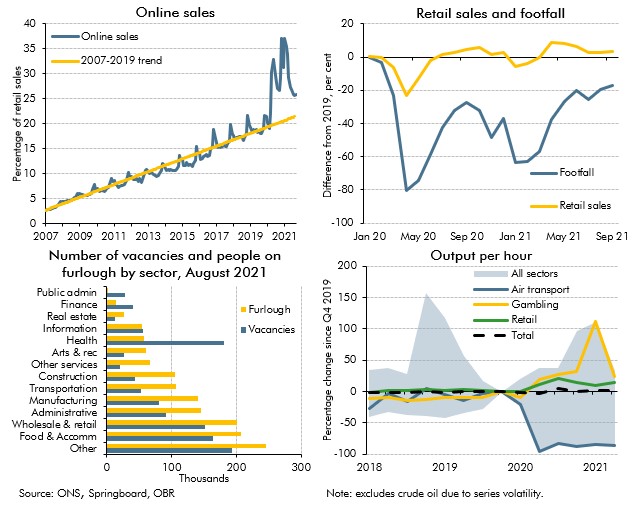

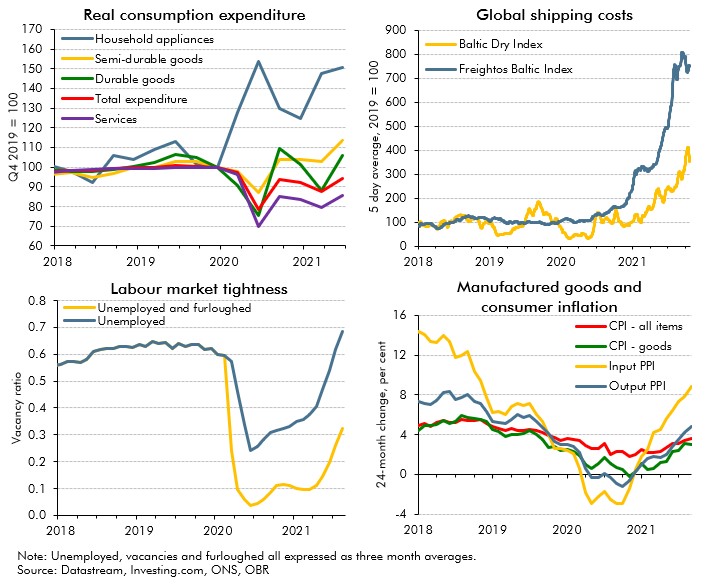

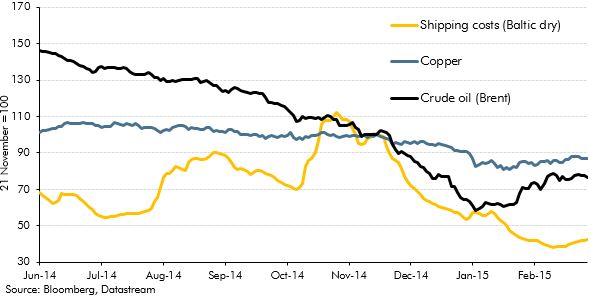

The recovery from Covid in the second half of 2021 was characterised by the emergence of imbalances between supply and demand in many markets. In this box we explored the impact of and outlook for these imbalances, or bottlenecks, in global product markets.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the run-up to our March 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook represented a significant adverse shock, primarily via a sharp rise in gas and oil prices. In this box, we considered where the UK gets its energy from and the channels through which higher energy prices raise inflation. We then set out how the economic shock from the invasion had been reflected in our forecast as well as several potential channels through which the invasion could affect the UK economy that our forecast did not explicitly capture.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast to take into account plans to loosen fiscal policy from 2022-23, to support households with the cost of living crisis, as well as for several specific measures, such as the cut in fuel duty and the freezing of the BBC liscence fee.

The labour market has seen mixed performance following the closure of the coronavirus job retention scheme. Low unemployment surprised to the upside whereas participation remained weaker than expected. In this box, we compared these weak participation outturns with two pre-pandemic counterfactuals, and explored the reasons why fewer people were active than we expected in previous forecasts, including by looking at the trends in different age groups. We also discussed whether we expected these trends to unwind over our forecast.

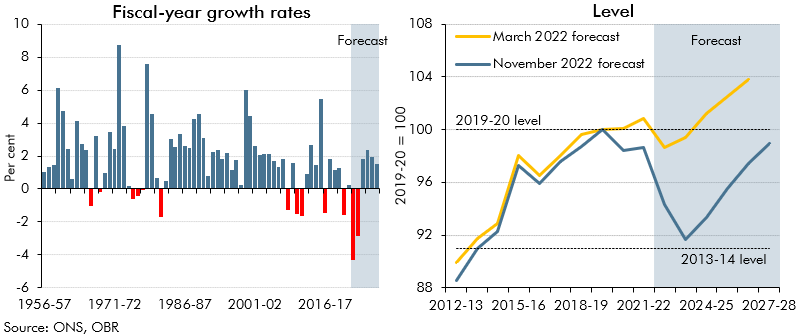

The cost of living has risen rapidly for households, with inflation reaching a 30-year high in January 2022 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine expected to increase inflation further. In this box we outlined our forecast for real household disposable incomes per person and explained that despite the Government's policy measures, 2022-23 is set to see the largest fall in living standards since ONS records began in 1956-57.

Our March 2022 EFO was published just over a year since the end of the transition period. In this box, we presented the latest evidence for the impact of Brexit on UK trade and considered the UK's recent trade performance relative to other advanced economies.

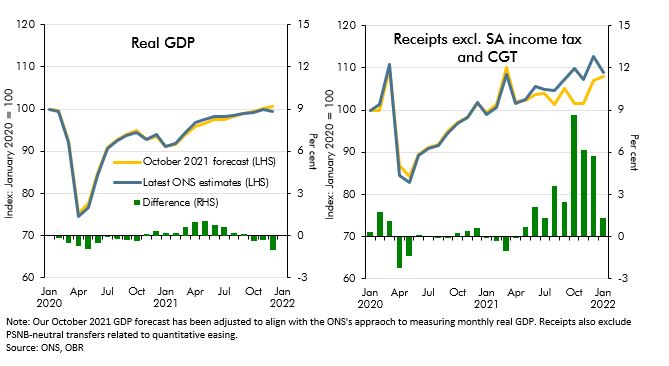

Since our October 2021 EFO the real economy has performed largely as expected in 21-22 but tax receipts have come in well above that forecast. In this box, we examined reasons why tax receipts have recovered so quickly particularly in comparison to economic data.

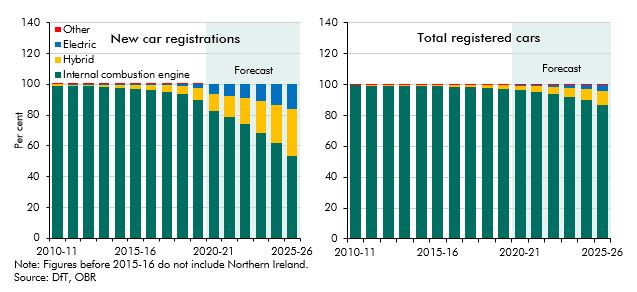

This box outlined the recent growth in electric vehicle sales and the fiscal implications of this and the role of policy in the transition.

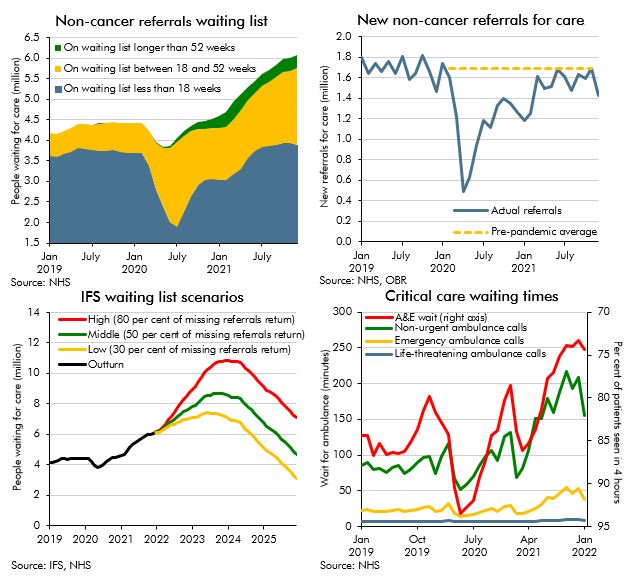

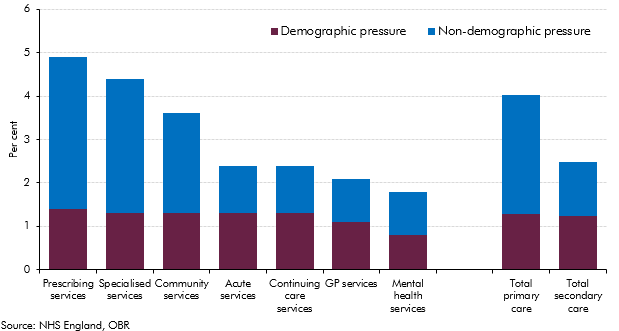

The NHS is the largest single item of public spending in the UK, and has been placed under extraordinary pressure as a result of the pandemic. Historically, some of the largest policy-related revisions have related to health spending, including the £13 billion a year announced at the 2021 Spending Review. This box explores indicators of pressure across the health service and the potential for these pressures to result in risks to our forecast.

In the final month of the coronavirus job retention scheme (September 2021), over 1 million people were still receiving payments from the scheme. In this box we explore the labour outcomes, up to January 20222, for this population after the closure of the scheme, compared to individuals in employment who were not on furlough in September 2021.

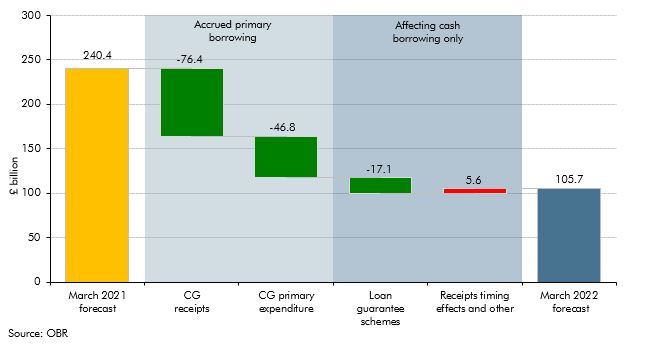

Forecasts for the government's cash borrowing in 2021-22 were revised significantly between the March 2022 and October 2021 forecast, with even larger revisions between March 2021 and March 2022. In this box we decomposed the sources of these revisions, and explained why cash borrowing outturn was much lower than forecast in March 2021, as well as why the revisions to cash borrowing were much higher than those for accrued borrowing.

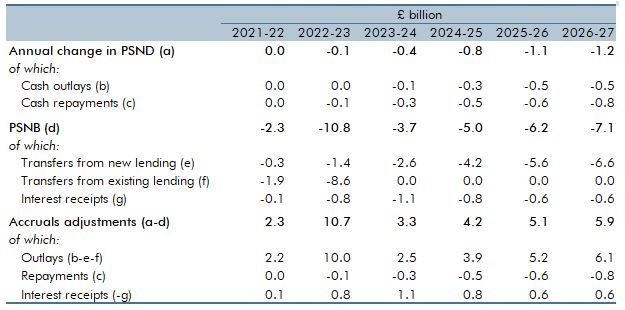

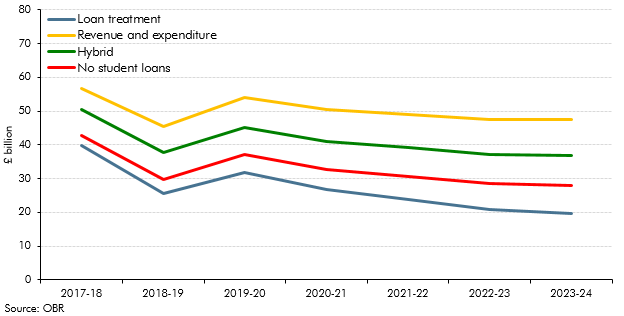

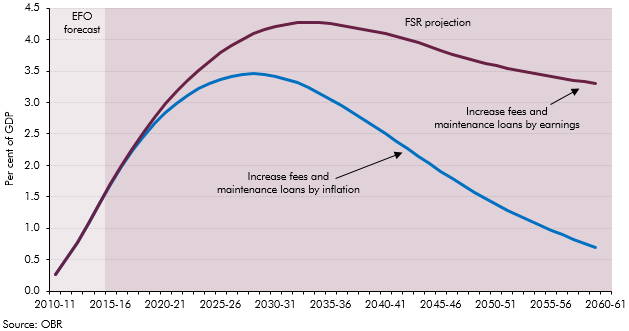

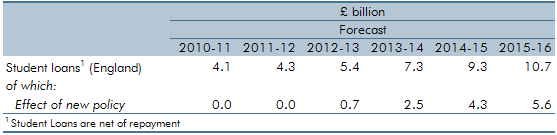

On 24 February 2022 the Government introduced a raft of changes to the working of the higher education student loans system in England. In this box we: summarised the reforms, explained their impacts on the complex accounting for student loans, and showed the overall impact on the latest forecast.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our October 2021 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast to take into account plans to loosen fiscal policy from 2022-23, as well as for several specific measures, including the impact of the HSC Levy on earnings.

Covid-19 caused dramatic changes in people's behaviour, which affected where, what and how much economic activity took place. In this box we examined the changes which appeared likely to outlast the pandemic, and the progress the economy had made in adjusting to them.

As we closed our pre-measures forecast earlier than usual at October Budget 2021, our forecast did not include the Quarterly National Accounts released on 30 September 2021, which contained Blue Book 2021 consistent revisions. This box examined the potential implications that including the latest data may have had on our forecast. We judged that the data revisions and other developments since we closed our forecast would have largely offset one another, leaving our economic forecast broadly unchanged.

In October 2021 commentators became increasingly concerned that the inability of supply to keep up with demand in specific areas of the economy would hold back the recovery. In this box we examined these 'supply bottlenecks' in energy, product and labour markets, discussing their consequences for wage and price inflation.

On 1 January 2021 some, but not all, of the provisions of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement came into effect following the UK's departure from the EU. In this box we looked at the initial impact of the new regime on UK trade patterns. We also considered whether the data was consistent with our assumption that Brexit will eventually reduce UK imports and exports by 15 per cent.

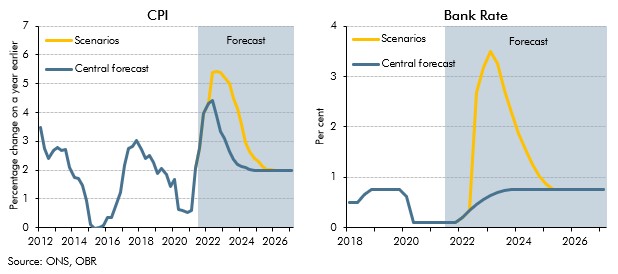

Inflation risks intensified after we closed our pre-measures forecast for the October 2021 Budget. This box showed two stylised scenarios embodying higher and more persistent inflation than in our central forecast to highlight the uncertainty surrounding the outlook. In one scenario inflation was driven mainly by pressures in the product market, and the other mainly pressures in the labour market, which had different implications for wages and consumption.

The pandemic generated only modest structural damage to the fiscal position but did still create a gap in what the Chancellor considered a sustainable fiscal position. This box compared the scale of fiscal consolidation facing the chancellor and his approach to repairing the public finances with the challenge that faced Chancellor George Osborne after the financial crisis.

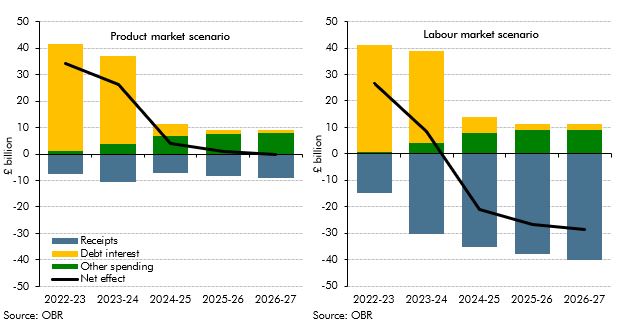

The level and nature of inflation has consequences for the public finances. This box explored the fiscal consequences of the sharp rise in inflation since our March 2021 forecast and examined the fiscal effects of the two scenarios described in Box 2.6 in our October 2021 EFO one where inflation is driven mainly by pressures in the product market, and the other mainly pressures in the labour market. The box concluded the labour market inflation scenario was significantly more beneficial for the public finances.

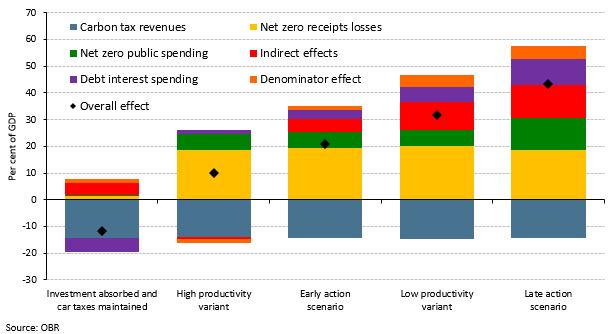

Our 2021 Fiscal risks report explored the fiscal risks posed by climate change and the Government’s commitment to reduce the UK’s net carbon emissions to zero by 2050. This box examined the policies announced in the Budget, Spending Review, and Net Zero Strategy in October 2021, and the significant rises in market prices for hydrocarbons since we completed our Fiscal risks report, and how they had changed the risks associated with climate change and decarbonisation.

Our pre-measures fiscal forecast was closed earlier than usual to give the Chancellor a stable base to make decisions for the Budget and Spending Review. This box described the impact of news since the forecast closed on headroom to the Government's fiscal targets.

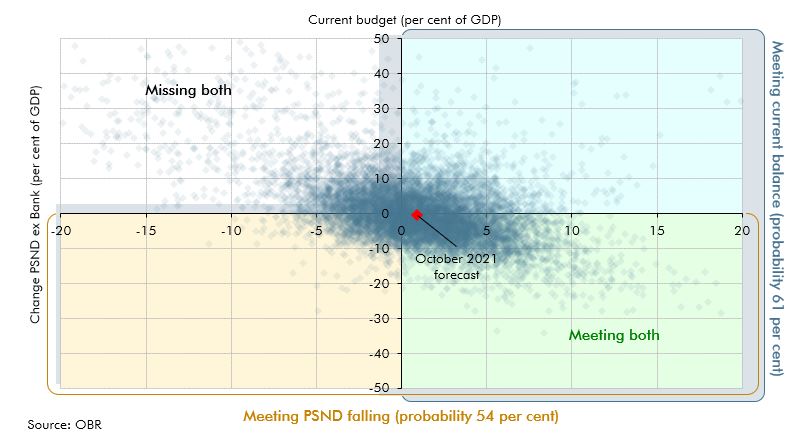

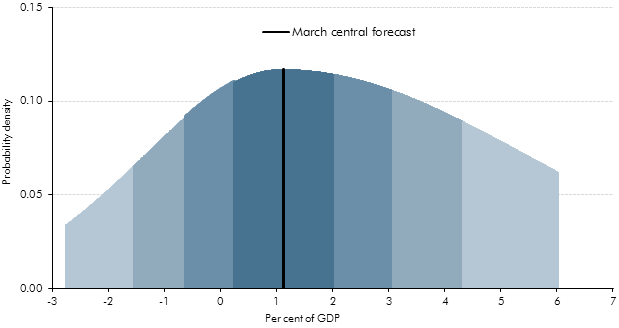

We illustrate the uncertainty around our forecasts using a variety of approaches. This box described using stochastic simulations to produce fan charts, which could be used to enhance presentation of uncertainty in future EFOs, and showed some experimental results.

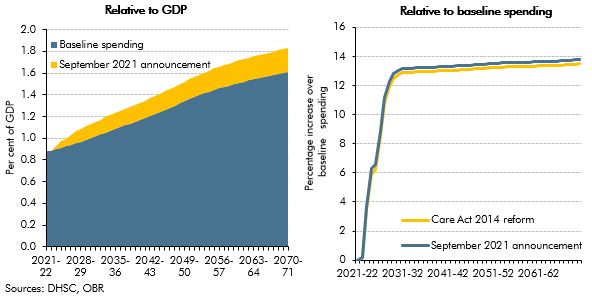

On 7 September 2021, the government announced a reform to the funding of adult social care in England. In this box, we described how this reform compares with the 2011 Dilnot Commission proposals and the reforms from the Care Act 2014 that were planned for April 2016 and then abandoned.

Fiscal space is an important consideration for how quickly and effectively a country's government can respond to a large shock. In this box, we explored different definitions of fiscal space over time, its multi-faceted nature and how the UK's position has evolved over the course of the coronavirus pandemic.

The Government announced in March 2021 that the coronavirus job retention scheme (CJRS) would be phased out completely by the end of September 2021. In this box, we looked at the latest evidence on the number of people on the scheme and their concentration in certain industries, as well as the latest data on vacancy rates. We also discussed how these data related to our labour market assumptions from March 2021.

Broader measures of the balance sheet are useful to consider when thinking about fiscal sustainability. However, under the national accounts framework even the broadest measures fail to recognise natural assets – the very assets affected by climate change. The box discussed the frameworks under which the ONS produces the environmental and natural capital accounts, and which bodies are working to address the gaps in these frameworks. The box also discussed key messages from the Dasgupta Review and Treasury’s response.

With the sale of new petrol and diesel cars to be banned from 2030, the transition to electric vehicles is a key element in the UK’s path to net zero emissions. This box outlined the recent growth in alternatively fuelled vehicle sales, the fiscal implications of this and the role of policy in the transition.

One of the greatest challenges in achieving net zero in terms of both cost and technical difficulty will be to decarbonise the more than 28 million homes in the UK that rely on fossil fuels for heating (typically gas central heating) and are, for the most part, poorly insulated. In this box we examined the similarities and differences between the future transition of domestic heating and one of the past, that of the switch to natural gas over the decade to 1977.

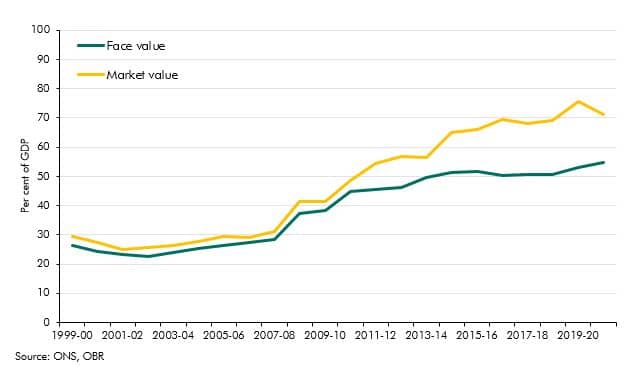

Government debt liabilities can be valued in various ways. In recent years market and face values have diverged sharply reaching 15% of GDP. In this box we explained why this has happened and why we use face value in our analysis.

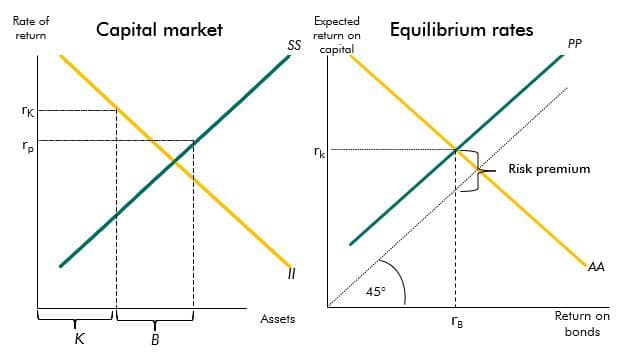

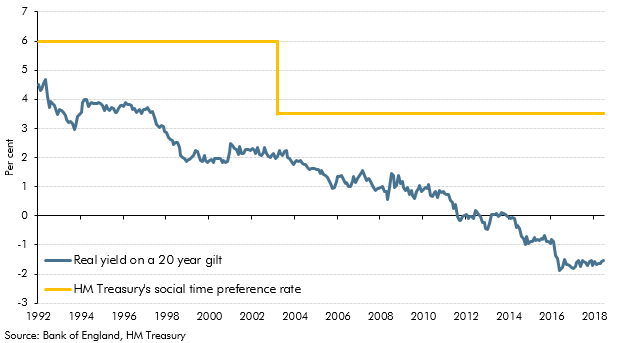

The yields on government debt have declined over recent decades. This box described a stylised model that provides a framework to explain the drivers of these changes.

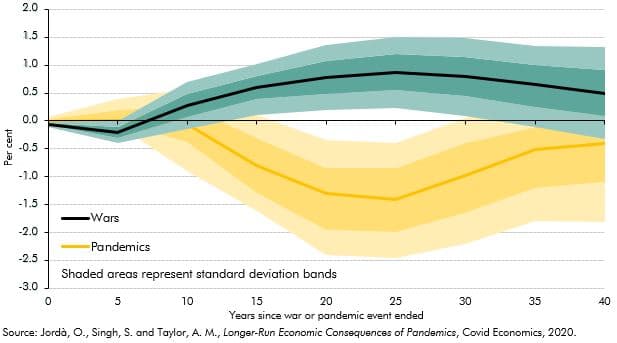

Past pandemics have had long-run impacts on real interest rates. A recent paper found that 20 years after a pandemic real rates fell by, on average, 1.5 percentage points (though less in the UK). This box examined the evidence for the current pandemic and suggested why this time it may be different.

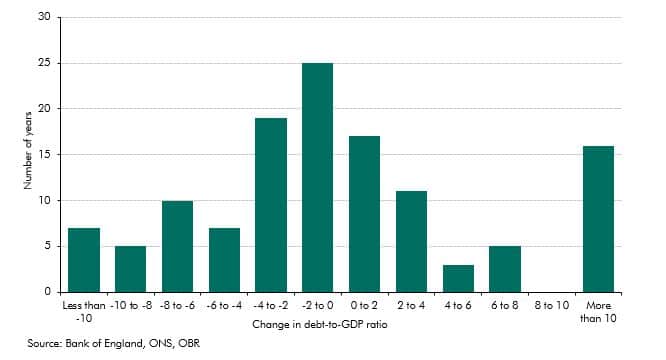

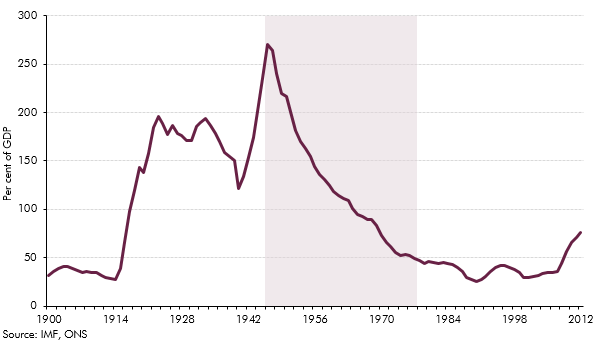

The history of UK government debt can be characterised as one of ‘punctuated equilibria’ in which long periods where the debt-to-GDP ratio is broadly stable or gradually falling are interspersed with occasional large increases in response to major shocks. This box looked at the instances of parge rises since 1900 and the long period of debt reduction after the second world war.

The Asset Purchase Facility (APF) houses the assets purchased by the Bank of England as part of its programme of quantitative easing. This box explained how this lowered interest rates benefitting the Treasury by £113 billion to date but it also increased the sensitivity of interest payments to future rate rises. The box showed how the cash flows to and from the APF change under various scenarios.

Cyberattacks are a growing global threat that, at the time of writing, had yet to cause sufficient disruption to national infrastructures to generate material economic and fiscal harm. We had not yet quantified the potential fiscal cost from cyberattacks, but included it in our Fiscal risk register for the first time. The box covered some of the potential types of cyberattack, their increasing prevalence and the mechanisms through which they might generate direct and indirect fiscal costs.

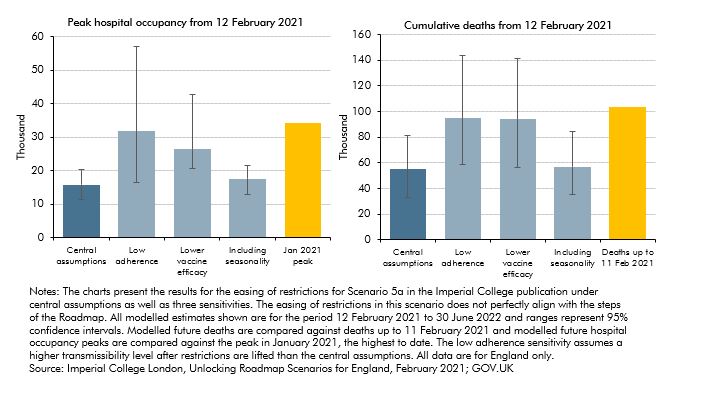

The path of the pandemic and the associated public health restrictions will be the most important near-term determinants of the UK’s economic and fiscal performance. Our March 2021 central forecast was conditioned on the Government’s ‘Roadmap’ for the lifting of restrictions and despite encouraging news regarding vaccines, there remains considerable uncertainty surrounding the future path of the pandemic and the economy. This box considered the uncertainties around key epidemiological assumptions on how the pandemic will unfold.

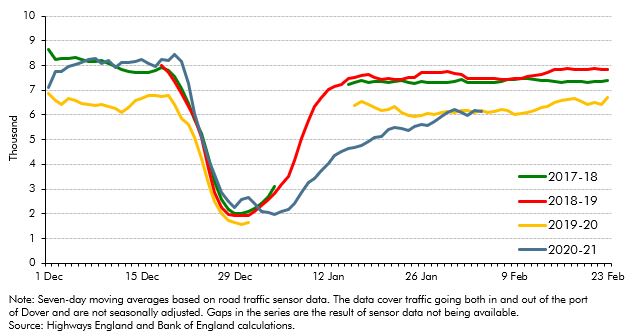

On 24 December, four and a half years after the EU referendum, the UK and the European Union concluded the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). This box compared the provisions of the TCA against our previous broad-brush assumption that UK-EU trade would take place under the terms of a ‘typical’ free-trade agreement. It also discusses the initial evidence regarding its short-term impact.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2021 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast to take into account plans to loosen fiscal policy in 2021-22, before tightening from 2023-24 onwards, as well as for several specific measures, including the impact on our business investment forecast of temporarily much more generous capital allowances.

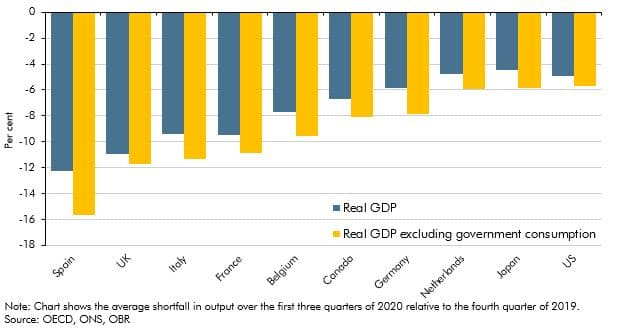

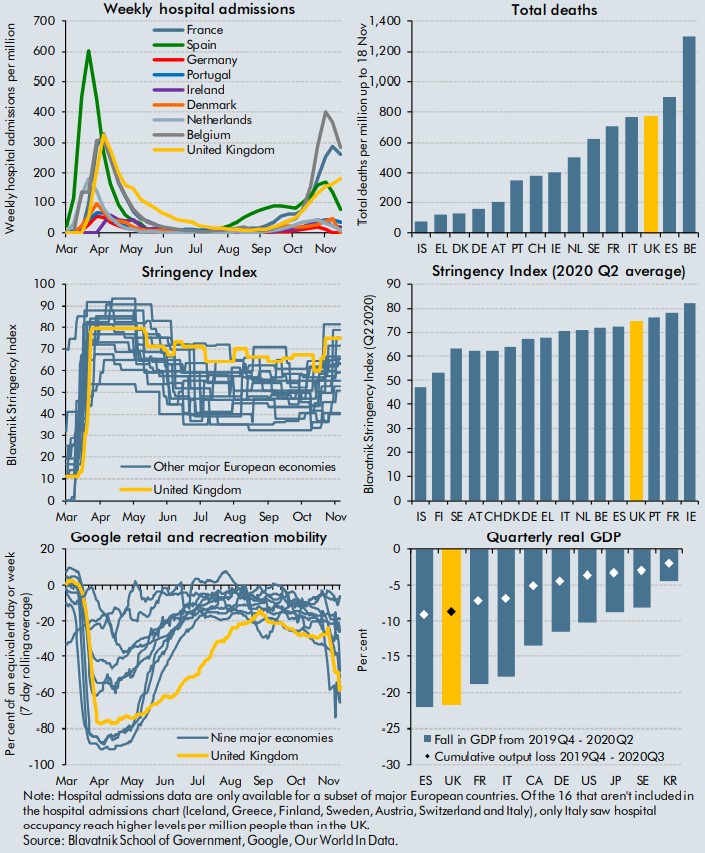

The coronavirus pandemic has affected economies of all countries around the world as a result of public health measures and voluntary social distancing. In this box we assessed how the UK had fared relative to other major advanced economics by examining the effect of using different measures of government output, the composition of these economies and the severity of the virus.

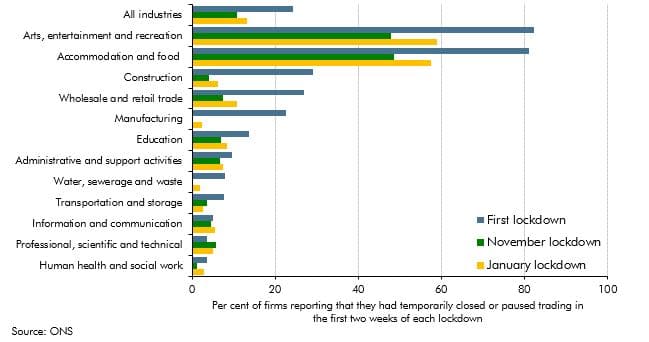

Output held up better in November 2020 than we had expected at the time of our November 2020 forecast. In light of this, this box considered whether the economy had become increasingly adapted to operating under lockdowns and other public health restrictions since the onset of the pandemic, and the implications that this might have had for the economy during the January 2021 lockdown.

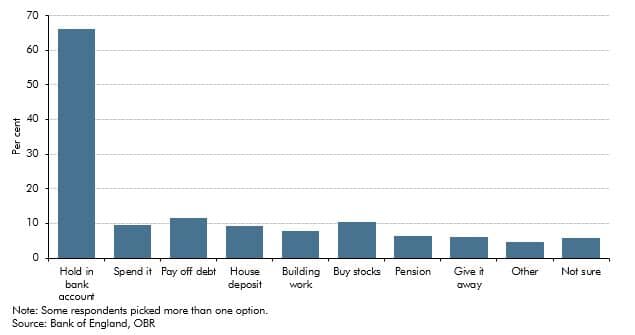

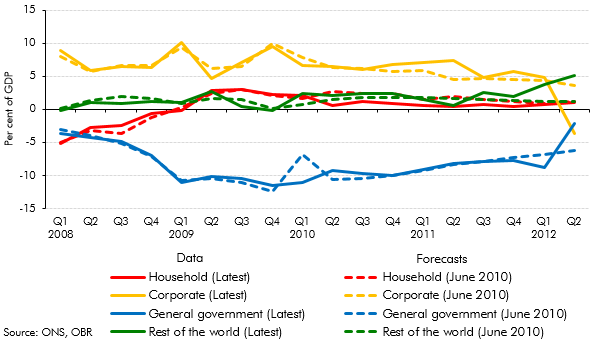

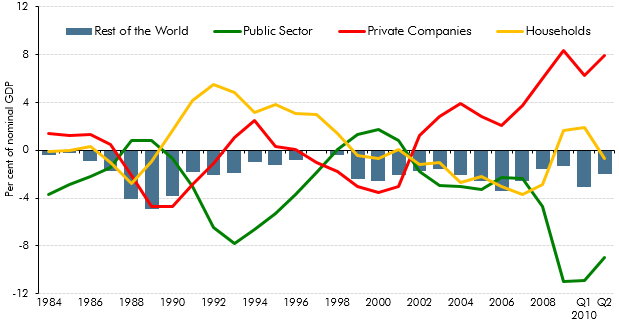

This box explored how the pandemic and associated policy response changed the flow of funds between the different sectors of the UK economy. It then considered the implications of how those flows unwind for the pace and sustainability of the recovery.

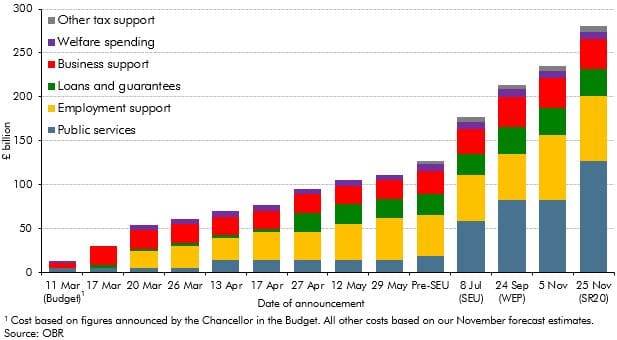

In the March 2021 EFO we estimated that policy measures responding to the coronavirus pandemic would add £344 billion to borrowing, with these policies announced across a number of statements beginning alongside the March Budget. This box updated on our estimate of this cost from November and the relative shares of support going to households, businesses and for public spending.

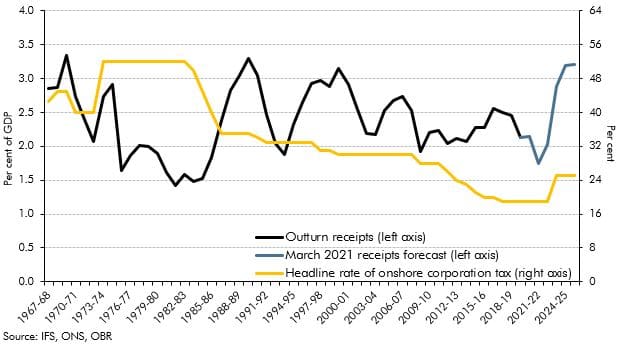

The rise in the main rate of corporation tax (CT) announced at Budget 2021, from 19% to 25% – from 2023-24, marks the first rise in the main rate of onshore CT since 1974. This box put this policy change in its historical and international context, by looking at onshore CT receipts as a share of GDP within the UK since its inception in 1965, and by looking at other corporate tax rates across OECD countries.

This box discussed the risks to our medium-term forecast of day-to-day departmental (RDEL) spending, particularly in relation to the impact of the pandemic.

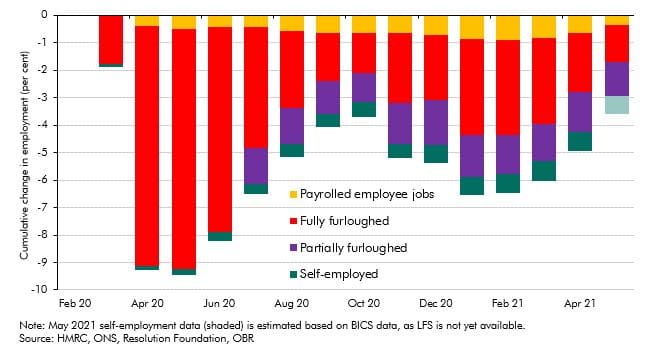

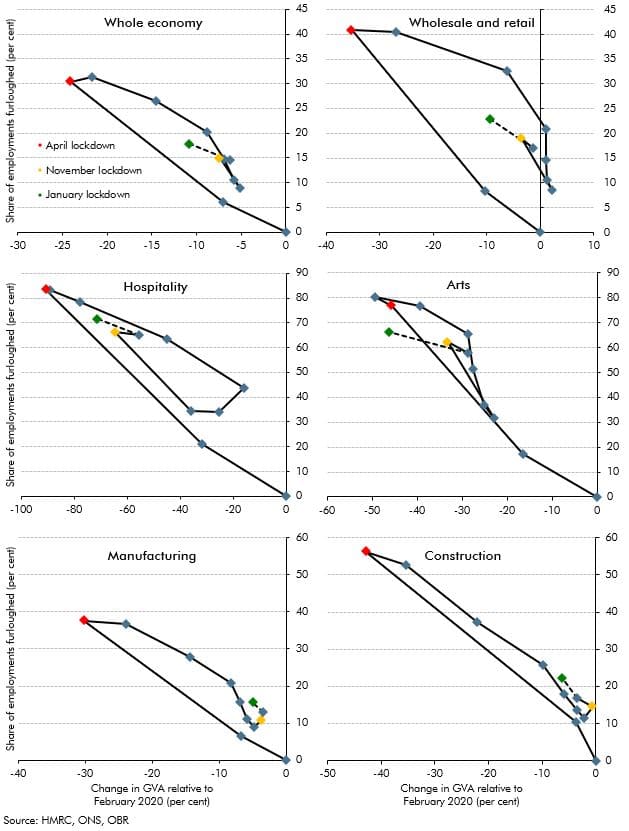

In this box, we discussed how the hospitality, wholesale and retail, arts, manufacturing and construction sectors, as well as the economy as a whole, adapted the usage of the furlough scheme in relation to output, and commented on the increased level of employees on furlough relative to the loss in output in the November 2020 and January 2021 lockdowns when compared with the April 2020 lockdown.

On 4 February 2021 the Government published its response to the December 2018 Court of Appeal ruling that the transitional protection arrangements in place across public service pension schemes based on years from retirement constituted a form of unlawful discrimination on the basis of age, commonly known as the ‘McCloud-Sargeant case’. This box explored the potential fiscal impacts of the Government’s remedy, as it was not possible to reflect the costs directly in our March 2021 EFO due to remaining uncertainty around the schemes’ implementation of the response.

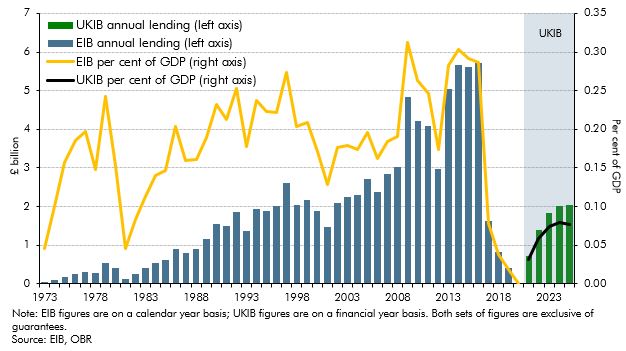

The Government announced the establishment of a new UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB) at Budget 2021 to tackle climate change and support regional and local economic growth. It does this in part by replacing some of the activity of the European Investment Bank (EIB). This box looked at how UKIB will operate and how this compares to the EIB, as well as briefly exploring potential fiscal and classification risks.

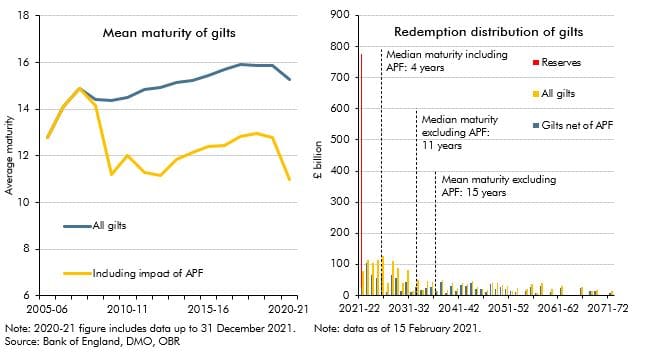

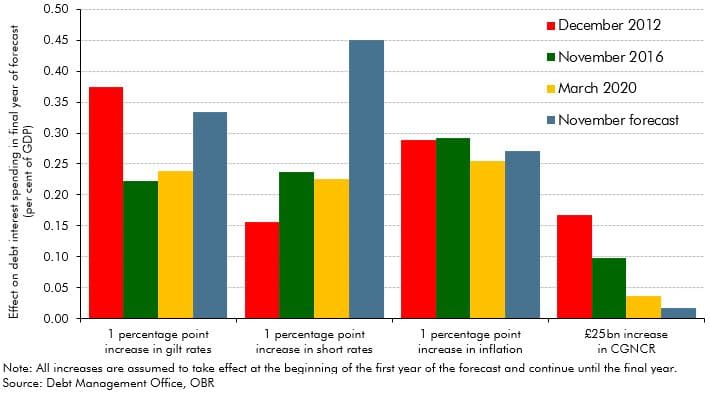

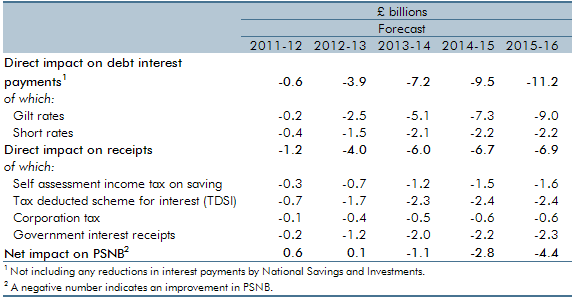

The average maturity of UK government bonds is longer than the average maturity of government debt in most other advanced economies. But the average maturity of the net debt of the public sector as a whole (including the Bank of England) has shortened considerably since the global financial crisis. In this box, we explored how the Bank of England's quantitative easing operations have shortened the maturity of public sector net debt, dramatically increasing the sensitivity of debt interest spending to changes in short-term interest rates.

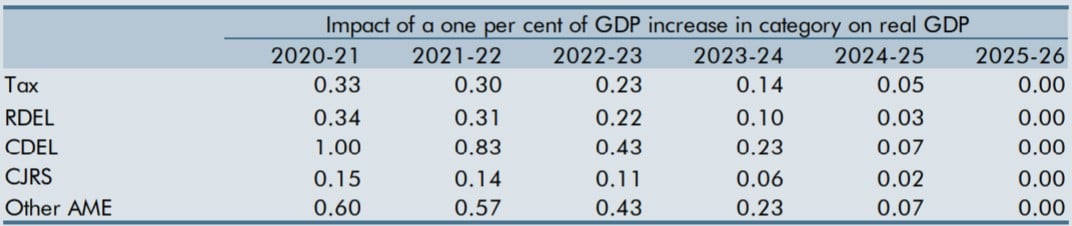

The unusual nature and size of the prevailing economic shock, and the Government’s fiscal response, raised the question of whether our usual fiscal multipliers were appropriate at the time. This box set out competing arguments for the multipliers being larger or smaller than those we usually employ and concluded that we would leave them largely unchanged.

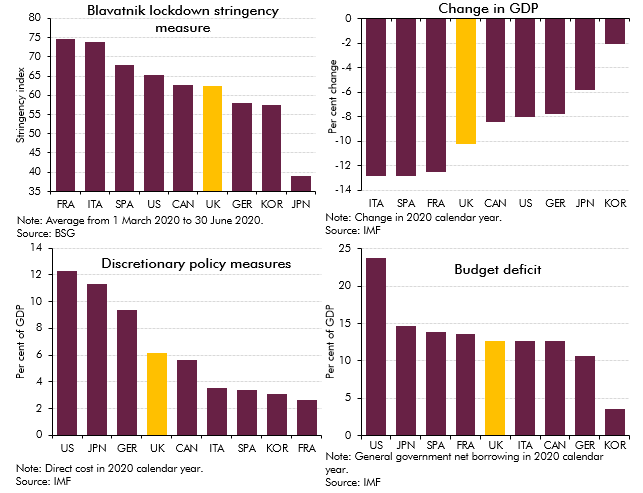

The coronavirus pandemic has forced governments around the World to introduce measures to curtail both the health, and economic impacts of the virus. This box aimed to compare the impacts on health and the economy of the virus with those of other selected countries, alongside the stringency of measures introduced by their respective governments.

In the November 2020 EFO we estimated that policy measures responding to the coronavirus pandemic would add £280 billion to borrowing in 2020-21, with these policies announced across a number of statements beginning alongside the March Budget. This box considered the main statements contributing to this cost and the nature of the support included in these announcements.

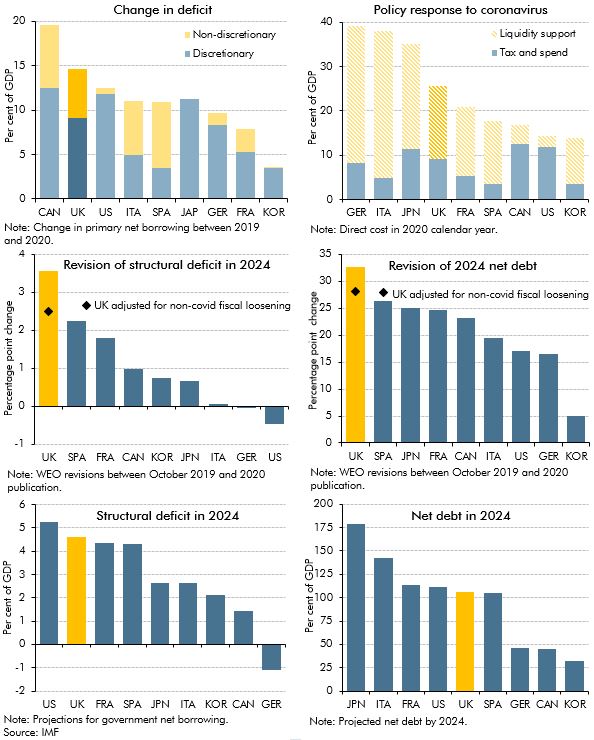

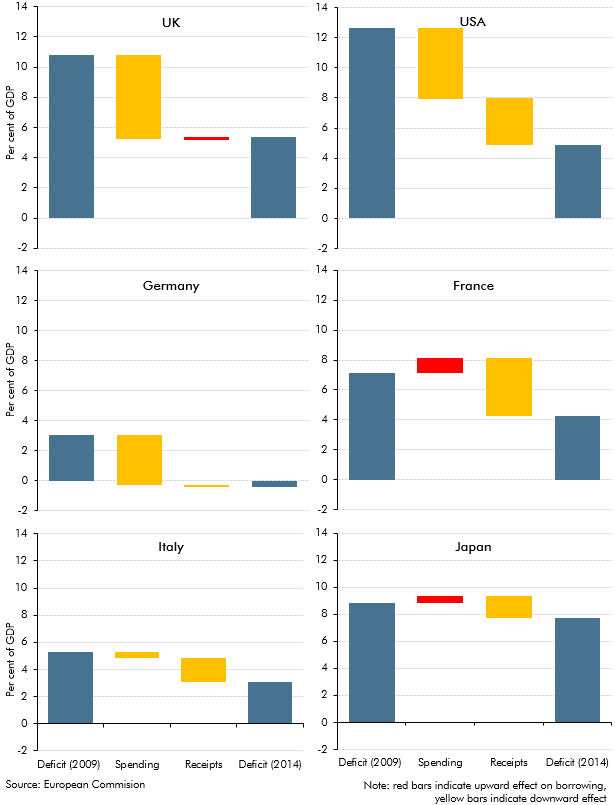

The pandemic has undoubtedly had a negative impact on public finances of countries around the world, but questions remain regarding the impact on the immediate and long-term fiscal positions of the UK relative to other major advanced economies. In this box, we considered the immediate term impact on primary deficits and the extent to which this reflected discretionary policy packages; the size of discretionary policy packages and the use of direct tax and spending policy versus liquidity support; and the impacts in the longer term on structural deficits and debt, including revisions between the IMF’s October 2019 and October 2020 WEO.

Despite debt rising as a share of GDP to a new post-war peak in our November 2020 forecast, government spending on debt interest was expected to fall to a new historic low as a share of total government revenue. This box explored how this had left the public finances more sensitive to future changes in the cost of servicing this higher debt burden.

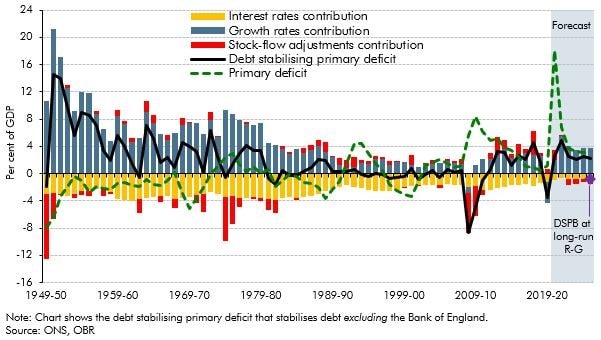

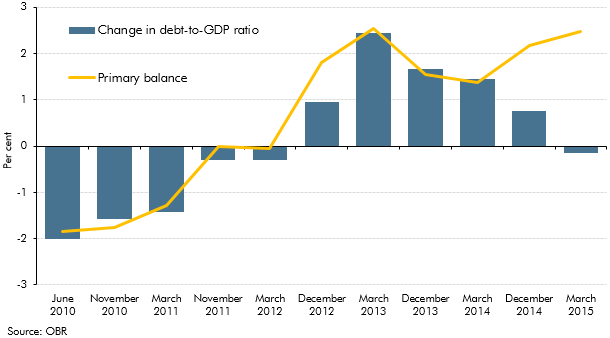

The debt-stabilising primary deficit depends on the level of debt, nominal growth rates, the effective nominal interest rate, and any 'stock-flow adjustments'. This box discussed the historical evolution of the debt stabilising primary balance, and also explained why it may appear to be ‘easier’ to stabilise debt the higher it rises, and the fiscal risks that such an interpretation entails.

On 8 July, the Chancellor announced further measures to support the economy as the lockdown is eased, which we were not notified of in sufficient time to incorporate into our scenarios. This box described the measures included in the package and the costs as estimated by the Treasury.

So far during the lockdown period, many businesses are struggling to meet their usual tax payment schedules and are seeking instead to delay those payments. In this box we considered the channels through which this might impact tax receipts and set out the key uncertainties in our medium-term scenario assumptions.

The coronavirus pandemic has hit the economic and public finances of all countries around the world as a result of lockdown measures imposed to control the outbreak and fiscal support provided to aid individuals and businesses. In this box we assessed how the UK had fared relative to other major advanced economics by looking at pandemic-related indicators and forecasts.

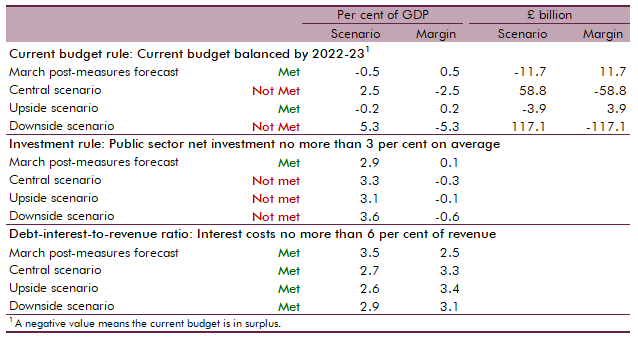

At Budget 2020 we assessed the Government's performance against the three proposed fiscal rules that featured in the Conservative Party's 2019 election manifesto. In this box we assessed whether the Government could meet these fiscal rules under our central, upside and downside scenarios.

On 31 January 2020, the UK left the EU and the transition period was set to finish at the end of 2020. This box set out our estimate of the effect of the EU referendum result on productivity to date. It also outlined the effect that leaving the EU and trading under the terms of a typical free trade agreement - which we assumed in this forecast - will have on productivity in the long run.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2020 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast to account for the material increase in departmental spending and tax policy changes on GDP and inflation. In addition to this, our business investment forecast incorporates the reversal of the planned cut in corporation tax, increases in the structures and buildings allowance and R&D tax credits.

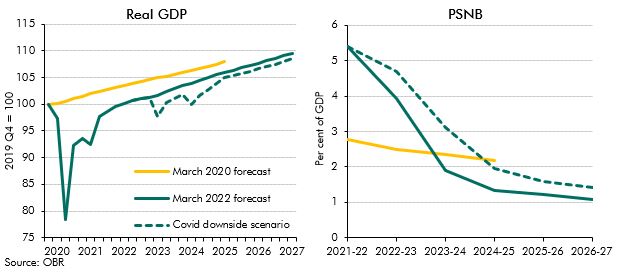

After we closed our March 2020 pre-measures forecast, it became clear that the spread of coronavirus would be far wider than assumed in our central forecast. This box described the effect we incorporated into the central forecast and explored the potential impacts the virus could have on the economy and public finances.

The Government announced plans for a new 'points based' immigration system set to come into place in 2021 that will align migration policy for EU and non-EU migrants. In this box, we considered the impacts of this new system on the outlook for potential output growth.

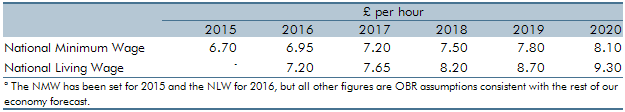

In March 2020, the Government introduced a new target for the National Living Wage (NLW) to reach two-thirds of median earnings (of the relevant population) by 2024, providing economic conditions allow. In this box we considered the effect of this policy change on the outlook for the economy and the public finances.

In April 2019, the European Parliament and Council adopted new regulations to set mandatory emissions targets for new cars. Ahead of our March 2020 EFO, the Government told us that all of these provisions transferred into UK law on 31 January 2020 under the terms of the EU Withdrawal Act. In this box we considered the effect of this change on the UK public finances.

The Government announced significant increases in departmental expenditure limits for capital spending. In this box we compared previous capital spending plans with outturn and our own capital underspend assumptions.

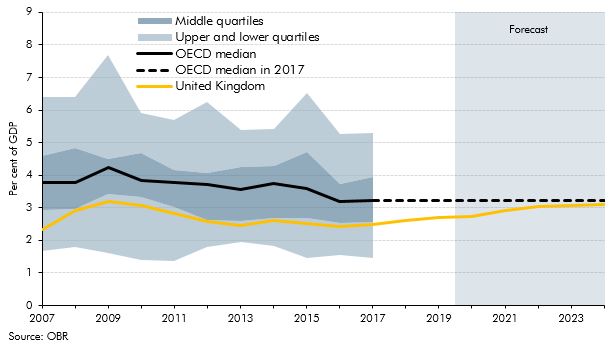

The Government committed to a significant boost to the path of capital spending. This box explored how UK government investment as a share of GDP has compared to other OECD countries and how our March 2020 forecast affects this picture.

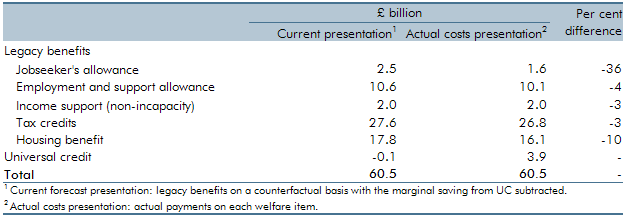

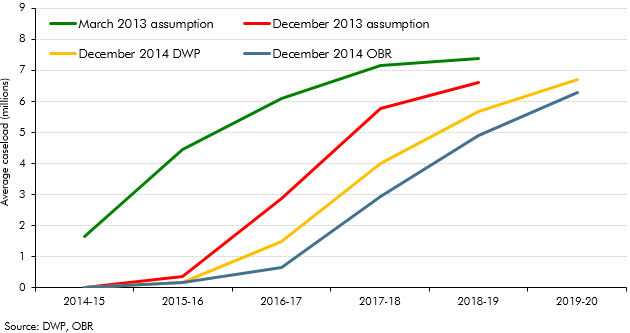

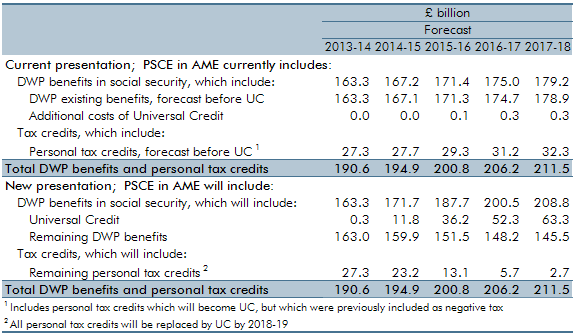

The transition to universal credit (UC) from legacy systems is a key component of our welfare spending forecast, as UC spending will represent 27% of total welfare spending by 2024-25. As detailed in our 2018 Welfare Trends report (WTR), we construct UC spending by forecasting the legacy system as though UC did not exist and then incorporate an estimate of the marginal cost of UC. This allows us to base as much of the forecast on as much administrative data as possible, but it does not directly reflect the real-world change in spending on legacy benefits as spending on UC rises. This approach is unavoidable at present but generates inevitable difficulties for our forecast. This box explored the challenges associated with this approach.

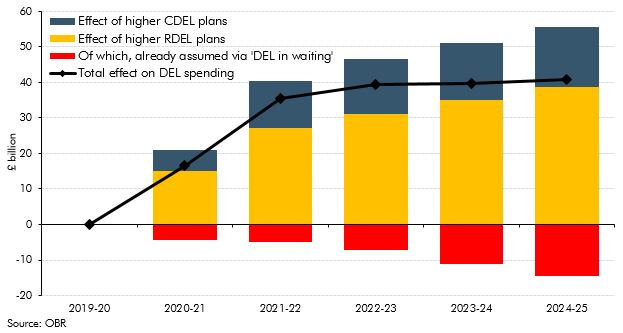

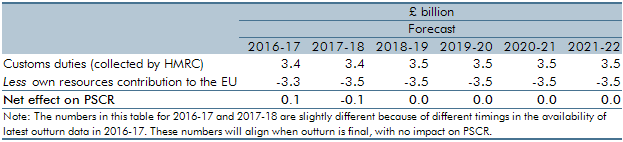

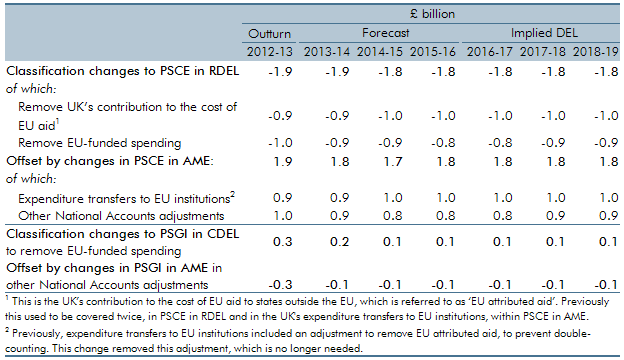

The UK’s exit from the EU presented fiscal savings to the Government in the form of transfers to EU institutions that featured in spending and retained customs duties. We assumed these would be fully recycled into substitute UK spending in previous forecasts. This box explained how we treated these flows as ‘DEL in waiting’ and how this related to the large increases in departmental spending.

In February 2020, the Government announced its intention to introduce a ‘points-based’ migration system from January 2021 that will align migration policy for EU and non-EU migrants. In this box we looked at the effect of the new migration regime on our borrowing forecast.

The Government used new fiscal rules to guide the policy decisions at this Budget. This box discussed the composition of two of these rules which had not previously been used in the UK.

Between our 2017 FRR and our 2019 FRR the Government undertook a number of initiatives to deepen its risk management. This box summarised these changes.

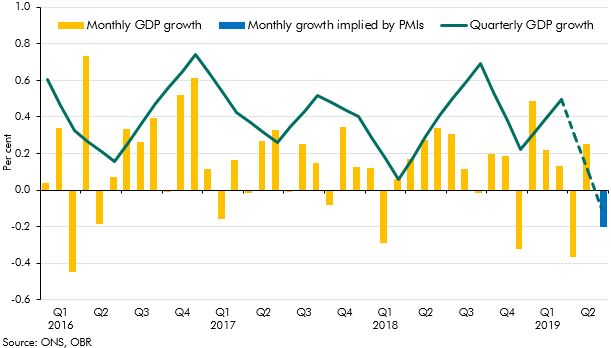

Monthly output data and the PMIs weakened in the second quarter of 2019, leading some commentators to suggest GDP would fall. This box considered what was behind the weaker data and whether it would persist into the third quarter, leading to a technical recession.

In June 2019 the BBC announced its decision to begin means-testing eligibility for Free TV licences for those aged 75 and over, based on households containing someone aged 75 or over and also claiming pension credit. This box explores the impact the BBC’s policy could have on pension credit take-up and welfare spending.

In recent years, local authorities have increased their 'prudential' borrowing to take advantage of the low interest rates offered by the Public Loans Work Board. In this box we discussed the example of Spelthorne Borough Council, looking at some of its riskier investments in commercial property and how those may pose a risk to the public finances in the event of an economic downturn.

Where the Government uses off-balance sheet financing to deliver public services this results in a 'fiscal illusion', where the recorded measures of debt and deficit do not reflect economic reality. In this box we looked at the case of housing associations (HAs). These came onto the balance sheet after the Government was given significant controls over them. The Government then legislated just enough to move HAs off-balance sheet. Neither movement made any fundamental change to fiscal sustainability.

The accounting treatment for student loans changed dramatically in 2019 adding more than £10 billion to the deficit. This box summarised the history of this change and a review into the design of post-18 education financing.

By issuing gilts linked to the Retail Prices Index (RPI) the Government exposes itself to inflation risks on interest payments. In this box, we looked at how changes to the formula for calculating RPI would affect our forecast.

The 2008 Climate Change Act requires the Government to assess the risks from climate change every five years. In this box, we looked at the most recent assessment published in 2017 and linked the six priority risk areas to how they are fiscal risks.

In 2016, the Office of Management and Budget and President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors produced a preliminary assessment of some of the fiscal risks associated with climate change. In this box, we describe the estimated potential costs of these fiscal risks, which could affect both expenditure and revenue.

In April 2019, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) issued a ‘call for action’ that sets out the next steps for assessing climate-related risks to financial stability. In this box, we looked at the scenario framework used by the NGFS, and the Green Finance Strategy – in which the UK Government set out how it will ensure the management of climate-related financial risks.

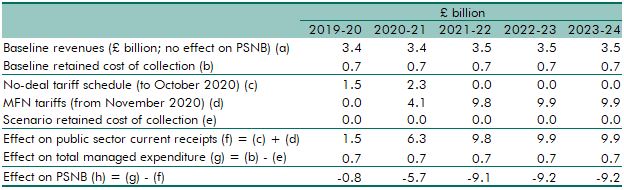

In the event of a 'no-deal' Brexit, the UK would be able to apply its own external tariff to goods imported. In this box, we explored the impacts of customs duties on borrowing, what a preliminary estimate of potential revenues would be and what else we would need to consider if this were to be our central forecast.

Survey evidence suggested that firms were building inventories ahead of the UK's exit from the EU. In this box we considered prospects for stockbuilding and the implications for GDP growth.

Presented with an improvement in the outlook for the public finances, the Government decided to loosen discretionary fiscal policy at this event. In this box we considered how Governments have responded to past pre-measures fiscal forecast changes.

Measures of reported disability prevalence are often subject to great variability and this can make drawing precise conclusions from them difficult. In this box, we considered two examples where measures varied. The first related to differences between Labour Force Survey and General Health Survey measures of working-age disability prevalence and the second to large changes in the former. We discussed differences in methodology and changes in attitudes as possible drivers.

Public financial support for disabled people extends beyond the extra-costs disability benefits and includes several other welfare payments. This box gave an overview of some of the most important interactions between disability and other benefits that provide support for disabled people.

Our ability to forecast accurately is heavily dependent on the quality of the data we can use. In this box we explained how statistical and expenditure data could be distorted by problems in delivery of the benefit, and the difficulties this creates in identifying emerging trends in the data.

There are several possible approaches to forecasting benefit spending. In this box we outlined the key issues the modelling of disability benefits needed to address, the three approaches we used to forecast spending, and the strengths and limitations of each, concluding that a combination of approaches was better than reliance on any single one.

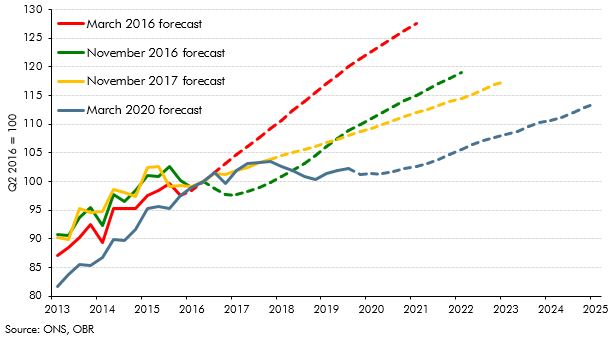

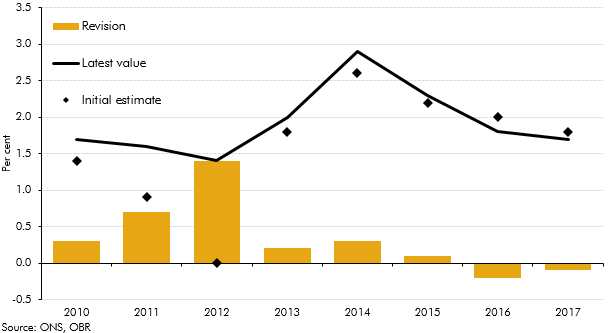

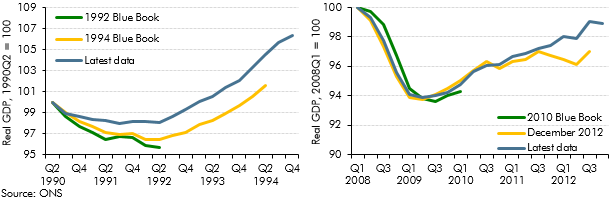

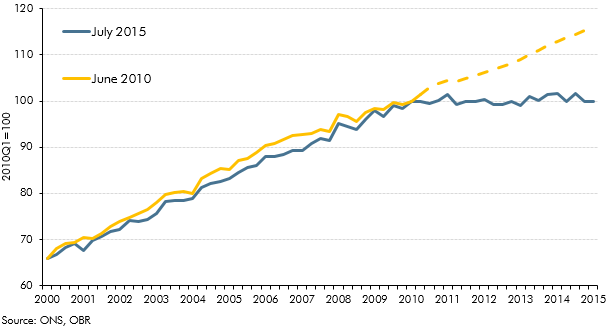

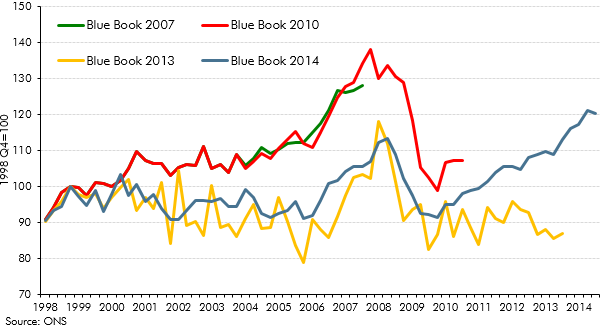

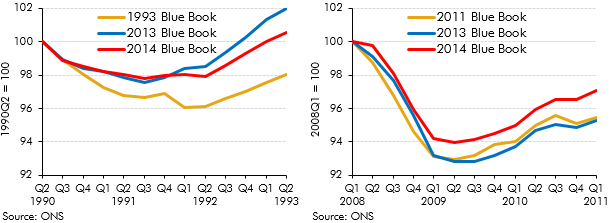

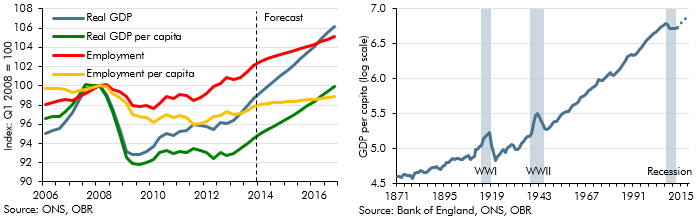

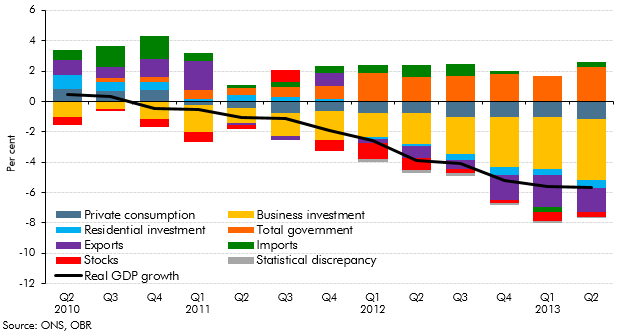

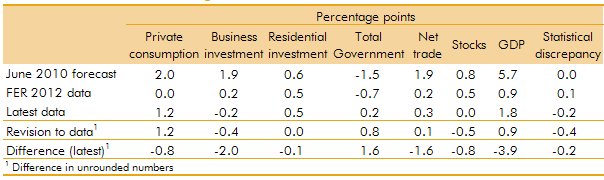

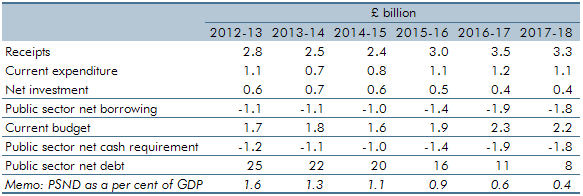

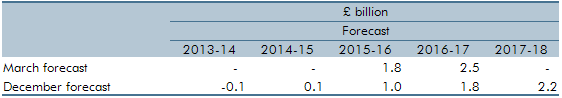

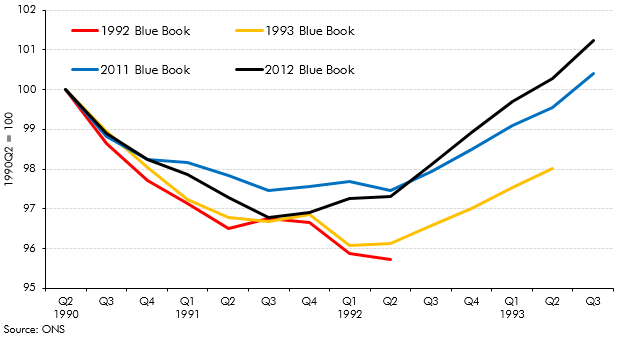

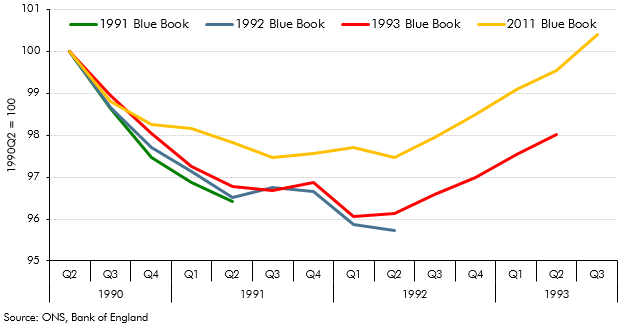

Revisions to National Accounts data are a normal part of the Blue Book process, which reconciles the different measures of GDP and incorporates information from annual data sources. This box explored how the estimated path of real GDP growth since 2010 has evolved over time, focusing in particular on revisions to GDP growth in 2012.

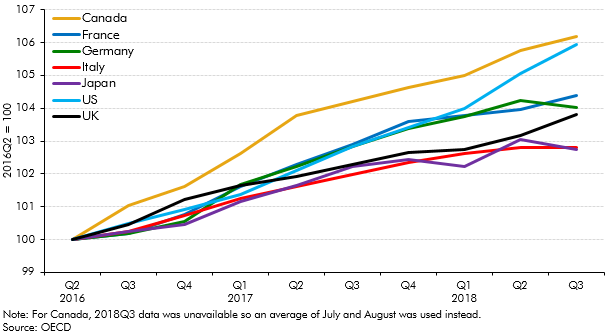

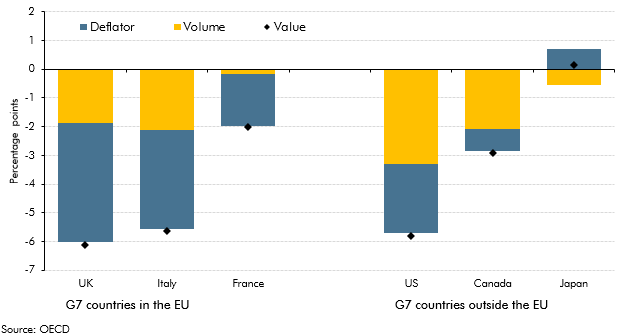

The vote to leave the EU had caused in a a slowdown in real GDP growth in the UK, with the main driver being weak investment growth. This box compared UK growth and investment since the referendum to that in the other major advanced countries in the G7.

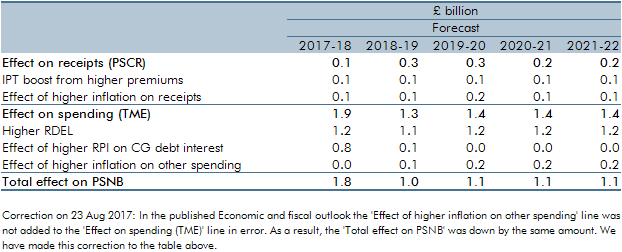

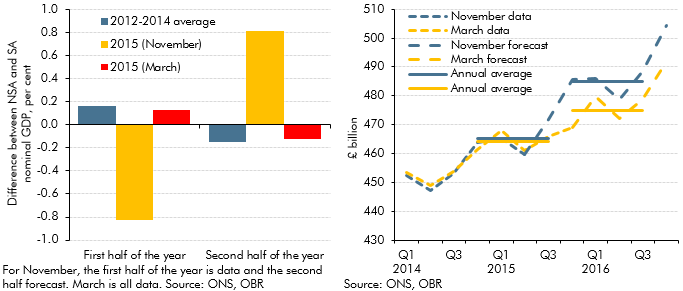

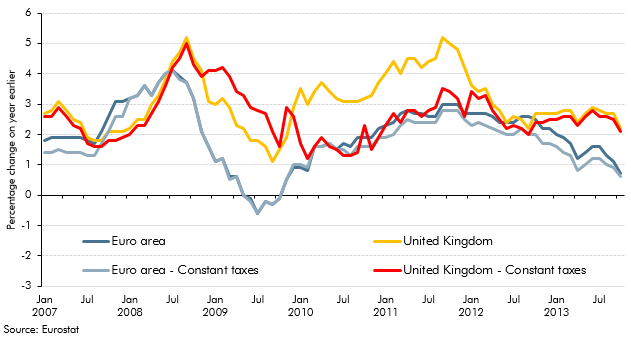

One unforeseen economic development affecting our March 2016 forecast was the upside surprise in inflation in 2017-18 as a result of the fall in the exchange rate. This box described the effect of that surprise on receipts, spending and borrowing.

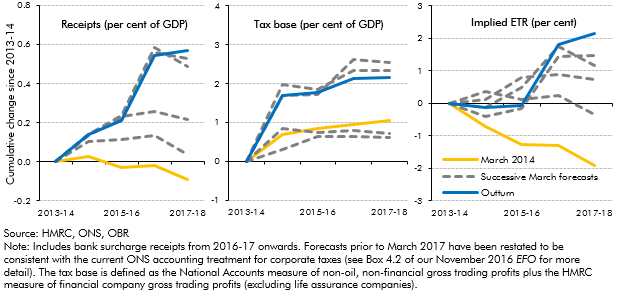

In recent years, onshore corporation tax receipts have repeatedly surprised on the upside. This box described the drivers behind that strength, in particular the contribution from a rising effective tax rate despite cuts to the headline rates.

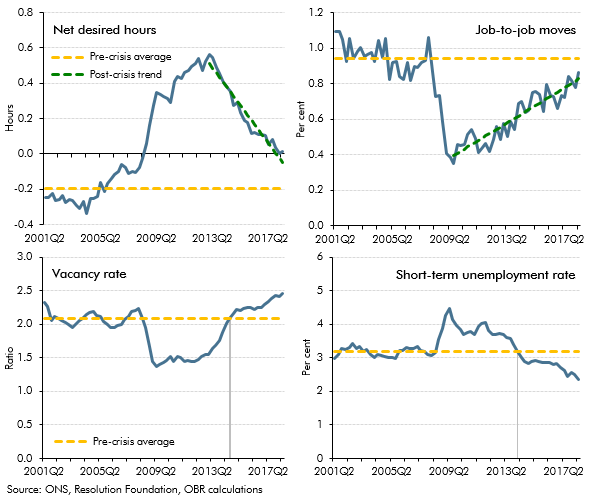

In the 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook we discussed how the unemployment rate – which had fallen to its lowest level since 1975 – may not necessarily give a complete picture of the extent of labour market slack. This box therefore looked at some other measures, some of which suggested there could be more spare capacity than was captured by the unemployment rate at that time and some of which could be used to argue that there was less.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our October 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook, economy forecast adjustments included the effects of looser fiscal policy on GDP and inflation, the effects of capital allowances on business investment, the effects of tax policy changes on inflation and the effects of the extension of the Help to Buy scheme on the housing market.

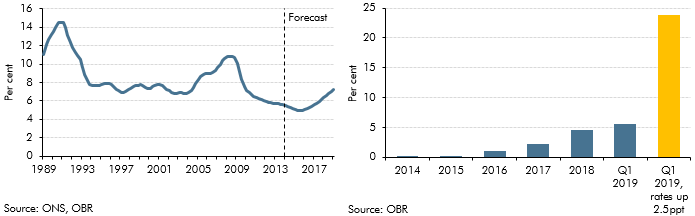

Alongside the October 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) the Government expressed its aspiration to end low pay, noting the definition used by the OECD, which corresponds to two-thirds of median earnings. This policy was not firm enough for us to incorporate into our central forecast. Nevertheless, in this box we drew on previous analysis from our July 2015 EFO – when the National Living Wage was first introduced – to illustrate the potential effect on the economy and public finances.

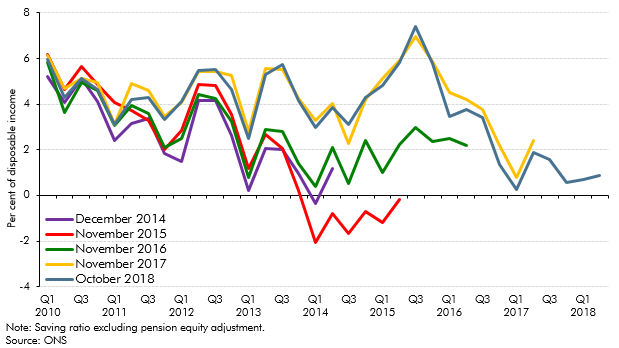

In our October 2018 forecast, the saving ratio – excluding pension contributions - was expected to turn negative, while unsecured debt was expected to rise steadily as a share of household income. In this box, we set out why this did not mean our growth forecast was dependent on a large and unsustainable increase in consumption, nor a significant expansion in consumer credit. Estimates of the saving ratio are subject to frequent revision, while only just over a third of unsecured debt relates to consumer credit, with a small and growing share made up by student loan debt. We also expect total interest payments on debt to remain subdued over the forecast period.

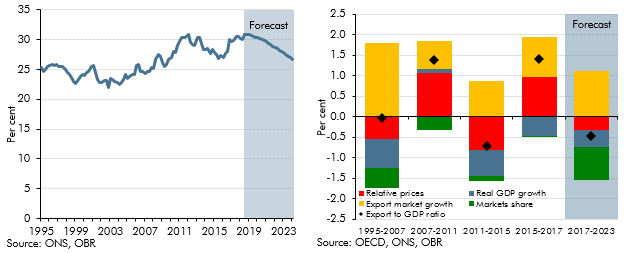

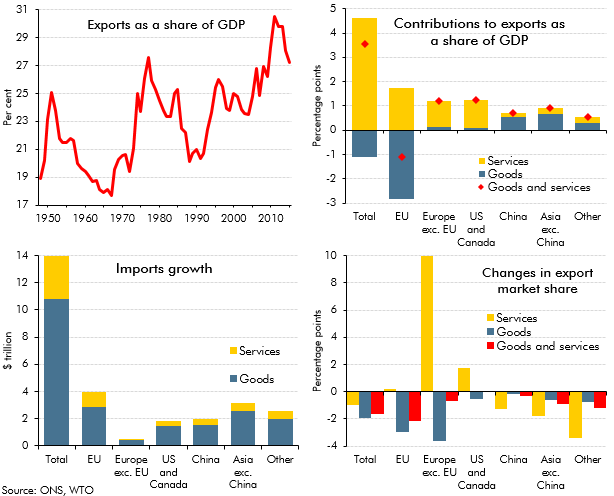

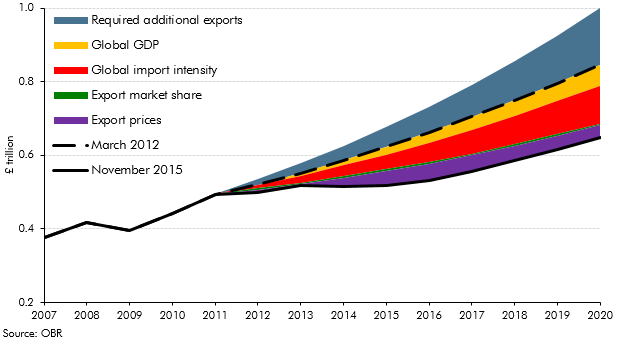

In August 2018 the Government announced an ambition to increase the UK's exports to 35 per cent of GDP. In this box we explored the drivers of previous changes in the exports-to-GDP ratio and how we expect it to change in our October 2018 forecast.

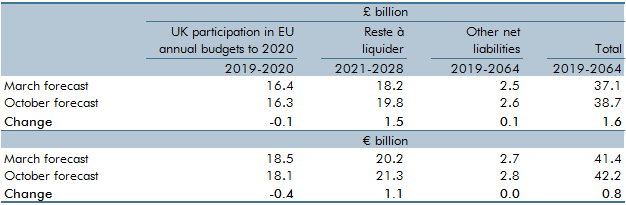

In the March 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) we set out in detail how we calculated the cost of the Government’s financial settlement with the EU. This box from our October 2018 EFO updated our estimate of the financial settlement’s cost and the reasons for the changes since March.

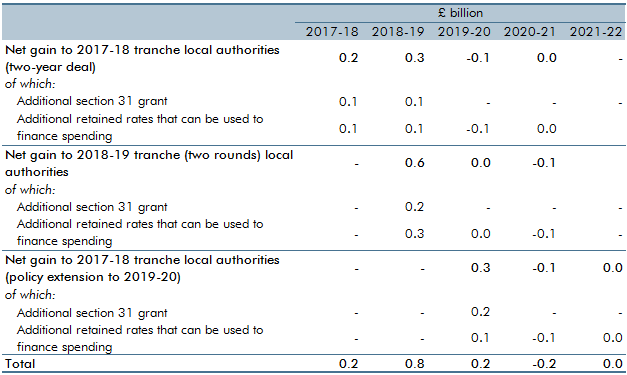

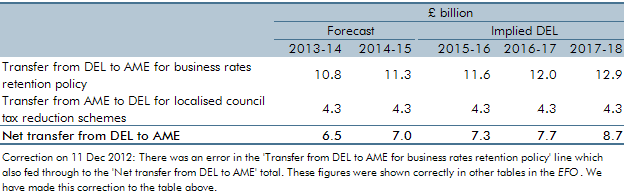

The Government has been piloting full business rates retention since 2017-18. These pilots featured in our forecasts from March 2017. This box reconsidered and re-estimated the fiscal effects of the 100 per cent local retention pilots scheme.

The accounting treatment applied to the burgeoning stock of student loans has been the subject of much interest over the past year, with reports from the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee and the Office for National Statistics. In July, we published our own contribution in Working Paper No. 12: Student loans and fiscal illusions. In this box we analysed the possible impacts of different accounting treatments on our estimate of the deficit.

We incorporate sales of financial assets in our forecasts when firm details are available that allow the effects to be quantified with reasonable accuracy and allocated to a specific year. In the case of the sale of student loans the government also considers whether a sale offers value for money. This box looked at the way in which the Government uses discount rates to evaluate value for money, how this does not mean the sales strengthen the public finances and whether future sales are likely to proceed.

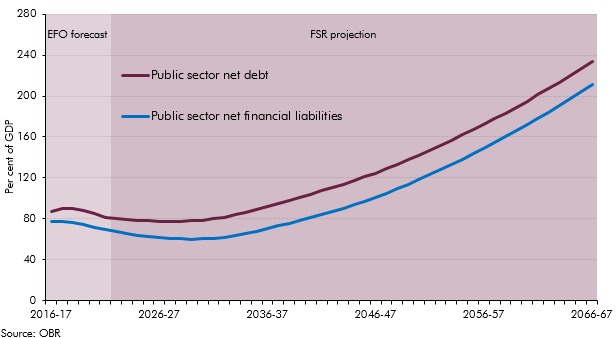

Public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL) is a wider measure of the balance sheet than public sector net debt (PSND) and includes all financial assets and liabilities recognised in the National Accounts. In this box we examined some of these differences and presented a projection of the components of PSNFL.

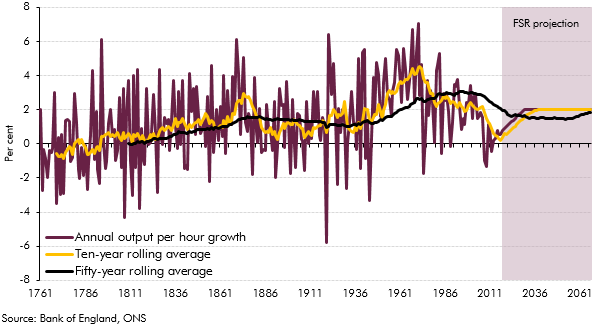

In our November 2017 EFO, we revised down our forecast for trend productivity growth so that it reached 1.2 per cent a year at the end of the medium-term horizon. For the purposes of the long-term projections in our 2018 FSR, we assumed that productivity growth would rise beyond the medium term to reach 2.0 per cent a year from 2030-31 onwards. In this box we provided context for our long-term assumption by exploring the rises and falls in UK productivity growth over the past two-and-a-half centuries.

The Government commissioned two reports published in 2017 to inform its review of the State Pension age (SPA): an independent review by John Cridland and a report by the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD). This box summarised the key findings from these two reports.

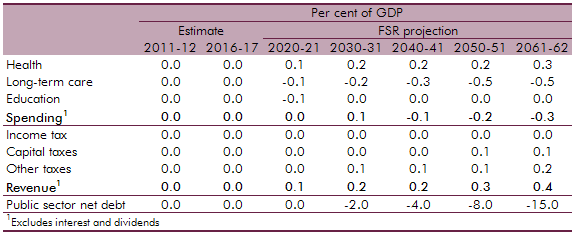

Our 2018 long-term fiscal projections suggested that, if left unaddressed, the public sector finances would come under increasing pressure over the next 50 years. This box compared our long-term age related spending projections over the period from 2025 to 2065 with those presented in the European Commission's 2018 Ageing Report.

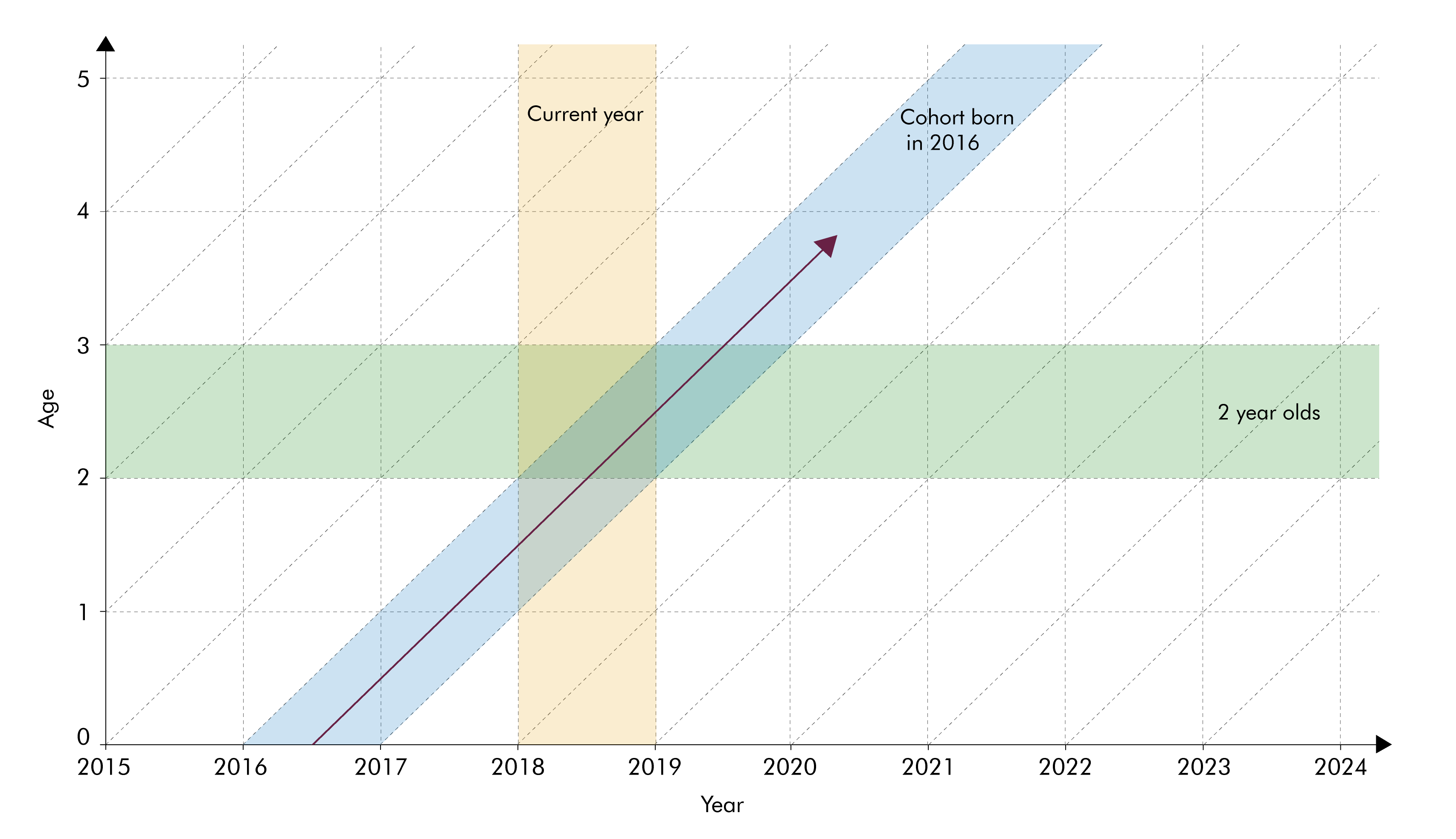

The population projections used to produce our long-term fiscal projections are underpinned by projections for age-specific fertility and mortality rates. In this box we considered two different ways of summarising trends in these rates - period and cohort metrics - and discussed their relative advantages.

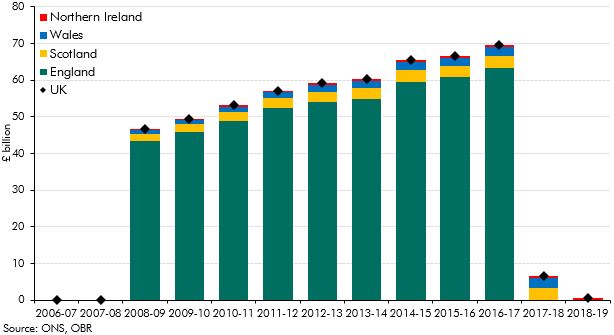

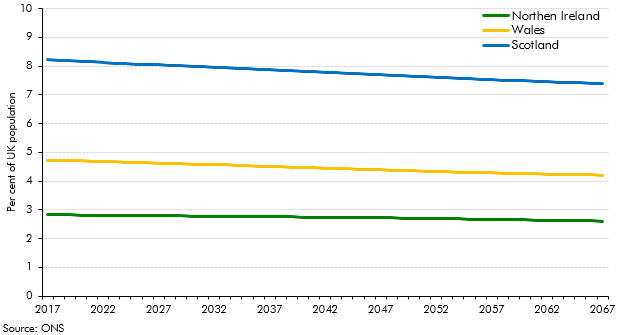

This box looked at differences in the Office for National Statistics’ population projections for the four constituent nations of the UK. It discussed the nations’ relative size and ageing, and possible implications for fiscal sustainability.

In the November 2016 EFO we made a number of judgements about how the vote to leave the EU would effect the economy in the near-term. This box from our March 2018 EFO compared these judgements against the outturn data that we had received since then, finding that most of these judgements were broadly on track.

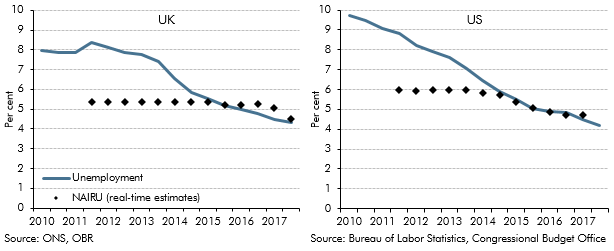

We revised down our estimate of the sustainable unemployment rate three times between 2015 and 2017, with unemployment falling faster than we had expected over that period but little evidence of rising wage pressure. This box from our March 2018 EFO compared the revisions we had made with those of the Congressional Budget Office in the US, which had faced similar issues when forecasting US unemployment.

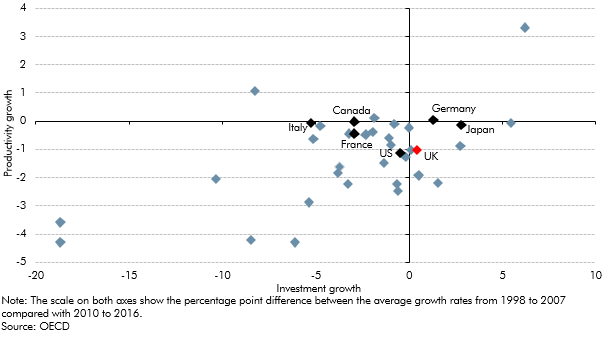

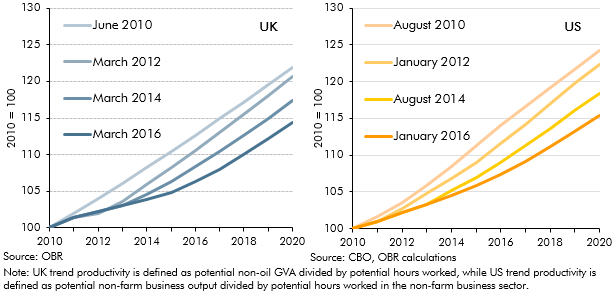

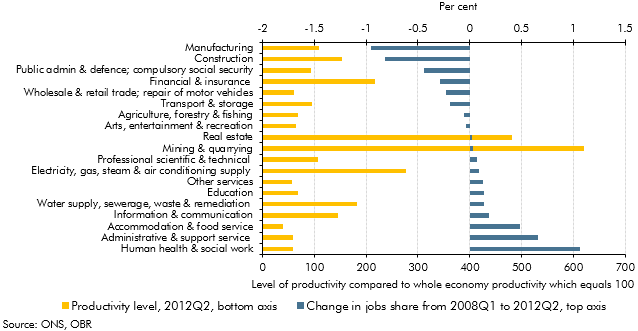

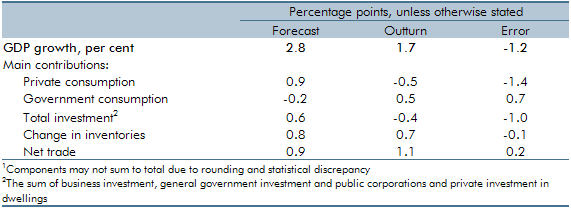

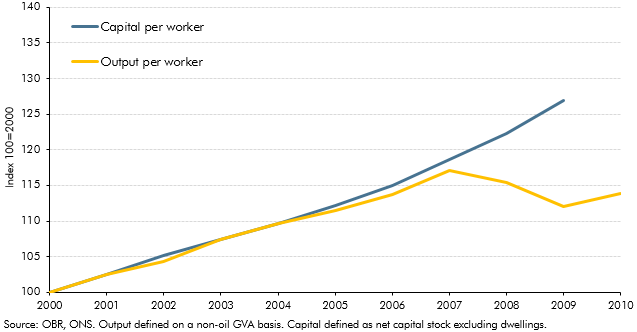

The outlook for productivity growth is one of the most important and yet uncertain areas of our economy forecast. In this box from our March 2018 EFO we looked at how actual productivity growth can be broken down into contributions from capital deepening and total factor productivity (TFP) growth and how differences in investment across countries could be related to post-crisis productivity performance.

Our first post-EU referendum forecast in November 2016 assumed that leaving the EU would result in a less open economy and lower productivity, but we did not incorporate an explicit link between the two over our medium-term forecast horizon. This box from our March 2018 EFO discusses why we did not include this link and what other forecasters have assumed.

The Pension Protection Fund is a significant part of the public sector, but as of March 2018 it did not appear in either outturn public finances data or in our forecasts. This box from our March 2018 EFO explained why that was the case, and why recent announcements from the Office for National Statistics meant that it represented a significant classification risk to our forecast.

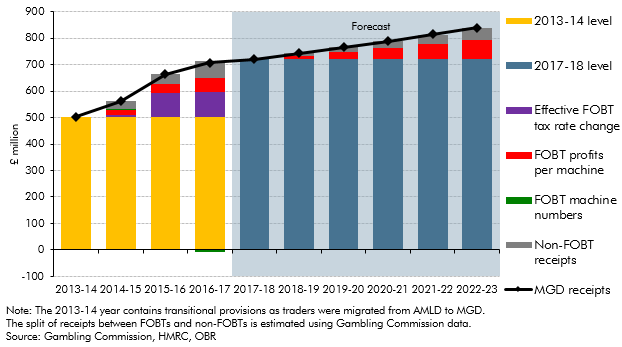

In 2017, the Government announced plans to reduce maximum permitted stakes on fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs) from £100 to between £50 and £2. This box from our March 2018 EFO explored recent trends in machine games duty (MGD) receipts and the contribution of FOBTs to them, illustrating the scale of receipts that might be affected by the planned policy change.

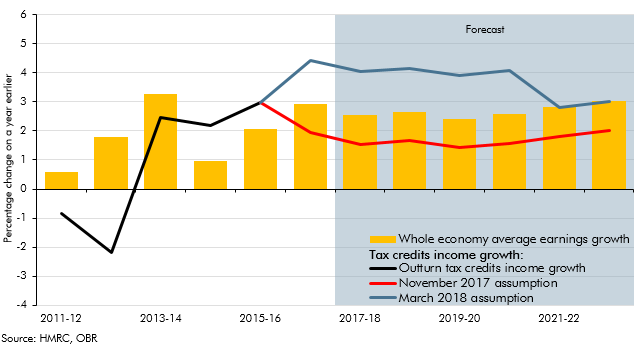

Spending on tax credits came in consistently lower than our forecasts from 2014-15 onwards. In our March 2018 EFO we increased our assumption for the growth in incomes of tax credits families relative to headline earnings growth, significantly lowering our tax spending forecast. This box set out the analysis that underpinned this change in forecasting assumption.

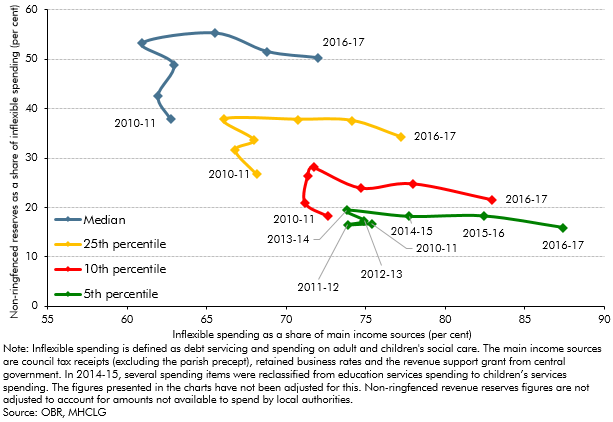

Local authorities’ net use of reserves (the amount they add to or drawdown from their stock of reserves) is a key judgement in our fiscal forecasts. This box from our March 2018 EFO examined two indicators of the general financial health of English local authorities over the period 2010-11 to 2016-17, assessing how these metrics might be used to inform our forecast judgements.

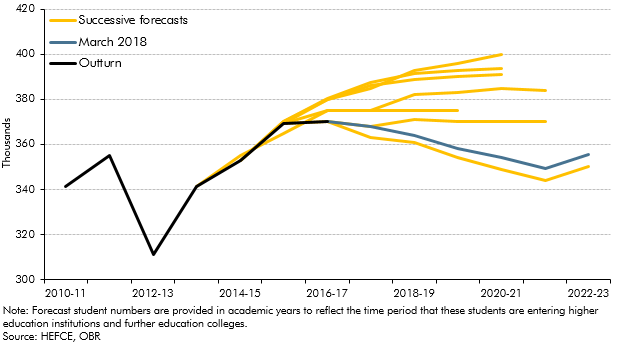

Student loans are the largest component of our financial transactions forecast, and even small changes to information about student numbers can have a significant impact on our public sector net debt forecast. This box from our March 2018 EFO discussed our previous and current student numbers forecasts and the factors that we take into account when producing them.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including how the 'work allowances' within it have been changed since the policy was first factored into our forecasts. This box looked at how our estimates of the net cost or saving from UC relative to the legacy benefits have evolved over time, and the important part played by Government decisions to reduce the UC work allowances.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including the role to be played by UC work coaches setting conditions and applying sanctions to encourage claimants to seek and progress in work. This box outlined the role, responsibilities and renumeration of work coaches, as set out in DWP's candidate information pack for applicants for the role.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). PSM is a static micro-simulation model that uses Family Resources Survey (FRS) data to analyse policy changes. This box detailed how the FRS is used in PSM and some of the issues that raises for our UC forecast.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). INFORM is a dynamic micro-simulation model that uses DWP administrative data to forecast the caseloads for different benefits. This box described how INFORM is used in our UC forecast and some of its limitations.

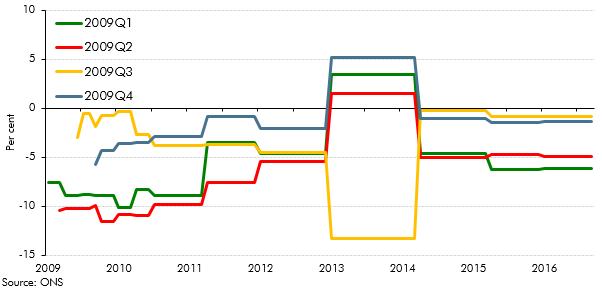

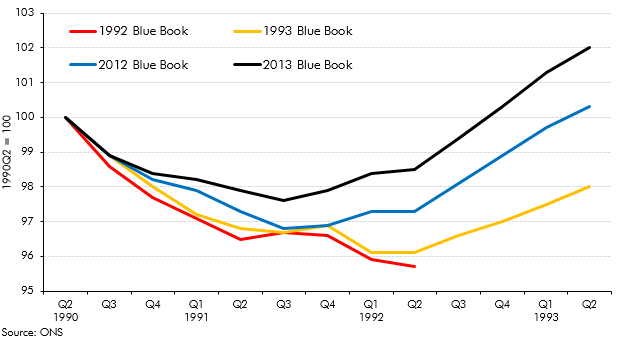

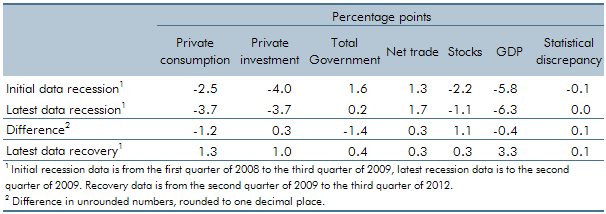

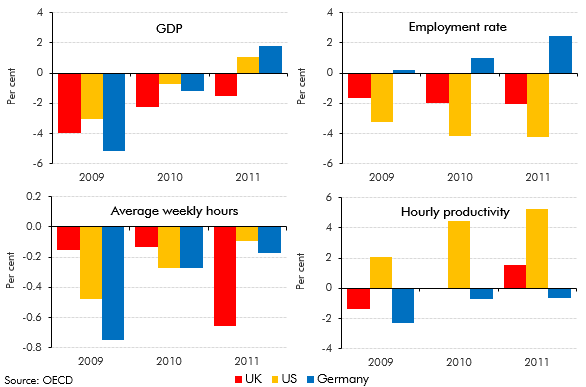

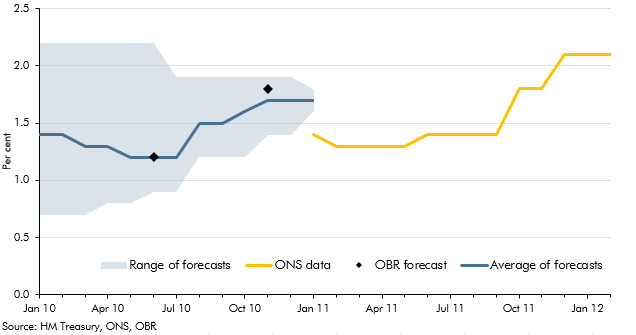

Revisions to National Accounts data are a normal part of the Blue Book process, which reconciles the different measures of GDP and incorporates information from annual data sources. This box explored how the estimated path of the 1990-92 and 2008-09 recessions and subsequent recoveries evolved over time, focusing in particular on revisions to GDP growth in 2011 and 2012.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook, economy forecast adjustments included the effects of looser fiscal policy on GDP, the effects of tax policy changes on inflation and the effects of stamp duty relief for first-time-buyers on house prices.

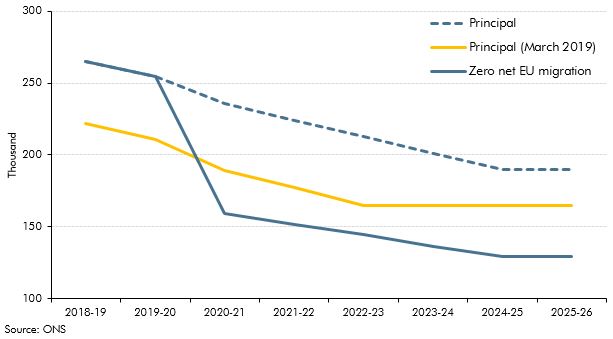

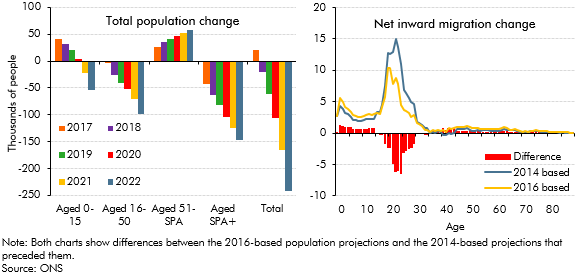

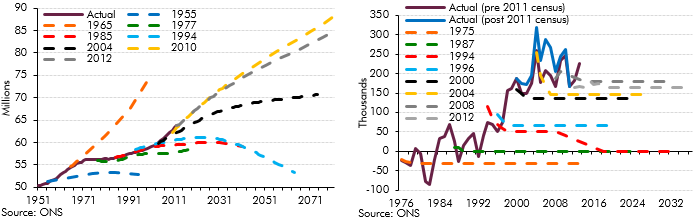

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published new UK population projections in October 2017, based on 2016 population estimates and updated assumptions for fertility, mortality and net migration. This box compared the latest projections with the previous 2014-based principal projections that underpinned our March 2017 forecast and summarised their effects on our November 2017 fiscal forecast.

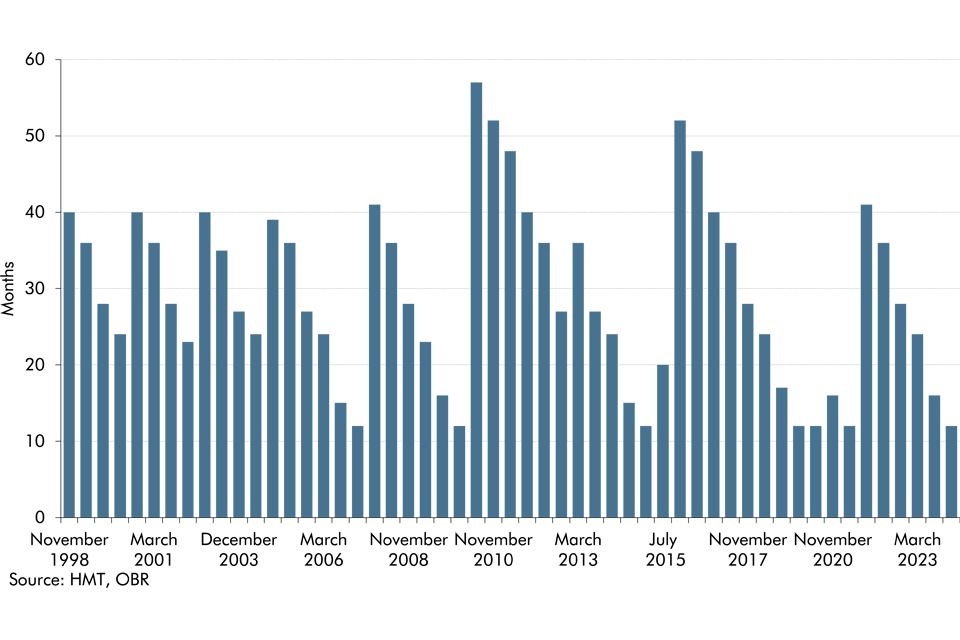

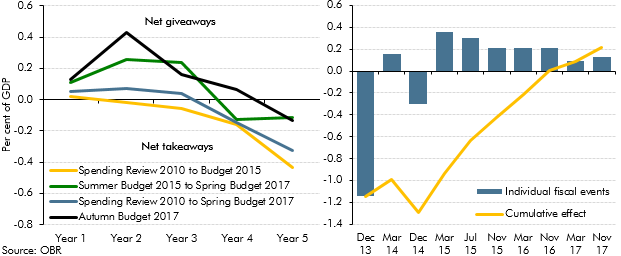

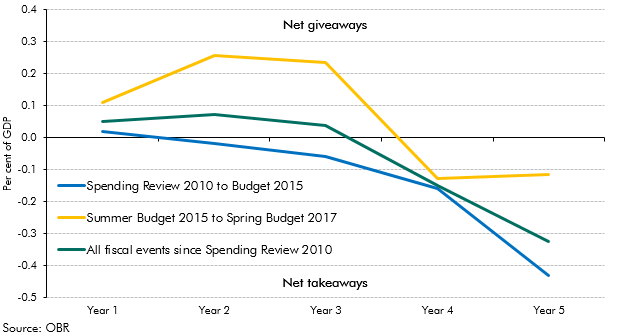

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we incorporate the impact of the policy decisions announced in the Chancellor’s Budget or other fiscal statement (the ‘fiscal event’). This box looked at how measures announced at the previous 16 fiscal events had tended to announce near-term giveaways but with the promise of takeaways in the later years. The Autumn Budget saw this pattern repeated.

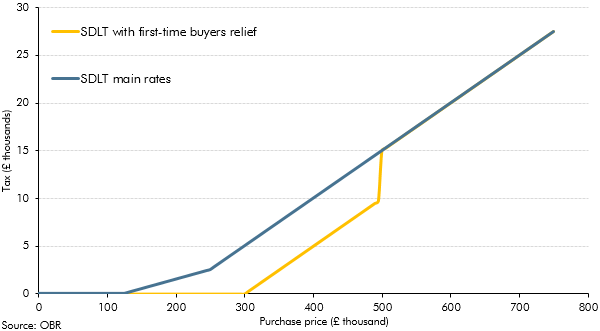

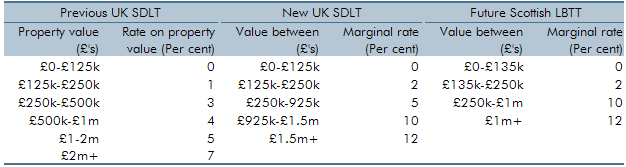

In Autumn Budget 2017, the Government announced the introduction of a permanent stamp duty land tax (SDLT) relief for first-time buyers. This box considered the effects of a previous temporary relief for first-time buyers and how the new permanent relief was expected to affect tax receipts and house prices.

Local authorities’ net use of reserves (the amount they add to or drawdown from their stock) is a key judgement in our local authority current spending forecasts as it directly affects borrowing. This box outlined recent trends in use of current reserves, split by English authorities with and without upper-tier responsibilities (such as education and social care), which underpinned our November 2017 forecast judgements.

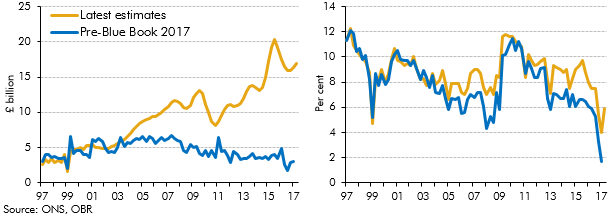

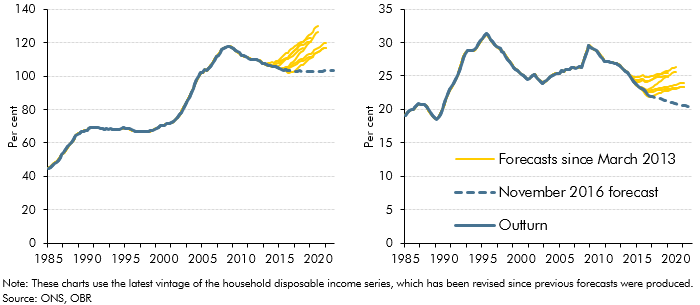

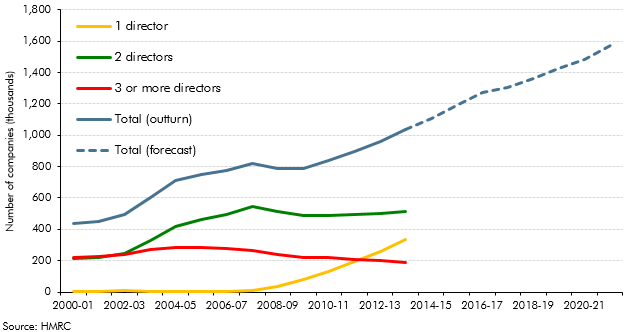

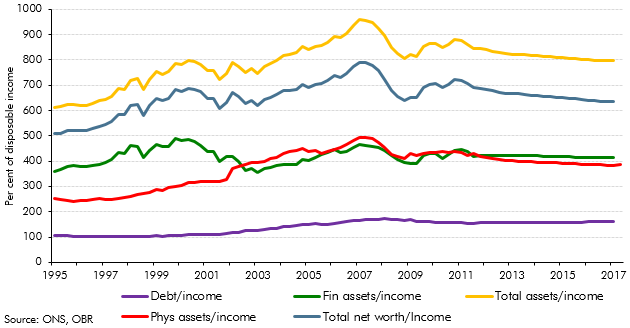

In recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of people setting themselves up as single-director companies (‘incorporations’), implying an increase in the share of household income received as dividends. ONS estimates of households dividend income were revised significantly as part of Blue Book 2017, and better capture this rise in incorporations. This box discussed the implications of these revisions, which implied a much higher level of household disposable income and household saving than previous estimates.

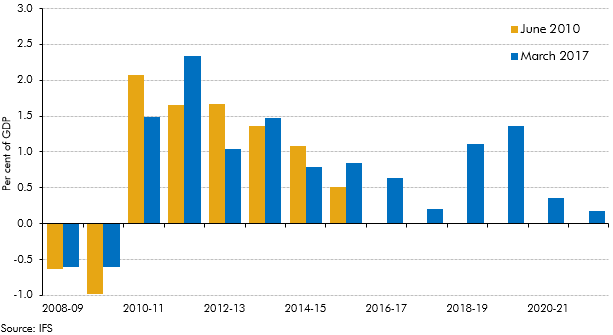

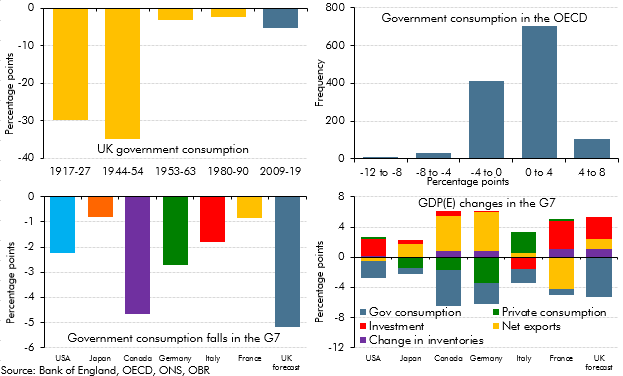

Over the past six years there has been a large discretionary fiscal tightening in the UK. This box set out estimates of the effect of fiscal policy changes on GDP growth, based on estimates of the consolidation produced by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) together with estimates of fiscal multipliers, which are drawn from the available empirical literature. The box also considered how changes in discretionary fiscal policy compared with our forecast errors for GDP growth.

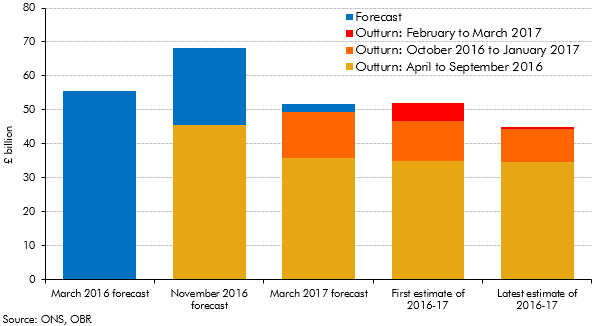

Initial estimates of the deficit can be revised significantly over subsequent months as more reliable data become available. This box set out how our forecasts during 2016 and 2017 evolved and how the outturns for 2016-17 were revised over time.

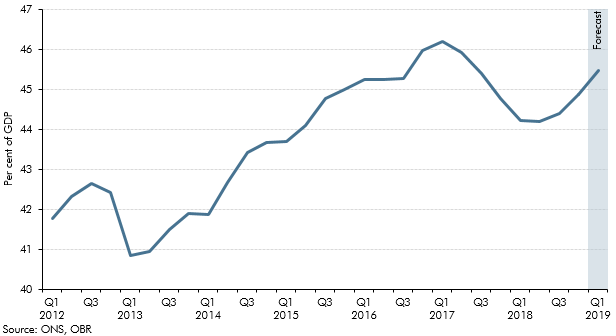

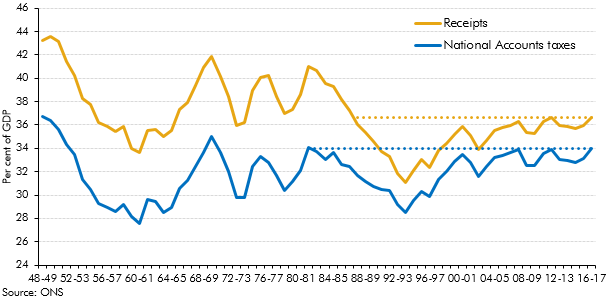

Strong overall receipts growth in 2016-17 took receipts as a share of GDP to their highest since 1986-87. This box explored how the composition of the public sector’s income has changed over the three decades since receipts were last at the latest share of GDP.

When discussing the potential impact of fiscal risks on the public sector balance sheet in our 2017 Fiscal risks report, we focused on the Government’s target measure of public sector net debt and its broader, but less-well-known counterpart, public sector net financial liabilities. In this box we considered some of the pros and cons of three even broader measures of the public sector balance sheet.

Our 2017 Fiscal risks report noted the historical and international evidence that financial crises have been a major source of risk to the public finances. Since the crisis of the late 2000s, the UK Government has reformed its regulation of the financial system. In this box we outlined key elements of those reforms, which aim to ensure that should a bank fail it can be managed in a way that protects the wider economy and financial system.

In each Budget or Autumn Statement, there are typically lots of policy giveaways (tax cuts or spending rises) and takeaways (tax rises or spending cuts). The net effect of these will be to raise or reduce borrowing in specific years and on average over the five years of the forecast – in other words to loosen or tighten fiscal policy. In this box from our 2017 Fiscal risks report we considered the pattern of those policy changes since 2010, noting that near-term giveaways are often financed by the promise of medium-term takeaways.

All elements of GDP data are subject to revision, which creates one source of uncertainty in our forecasts. Business investment data are particularly prone to revision. In this box from our March 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook we looked at past revisions in business investment data and compared the volatility and average revision of UK data with those produced by other countries.

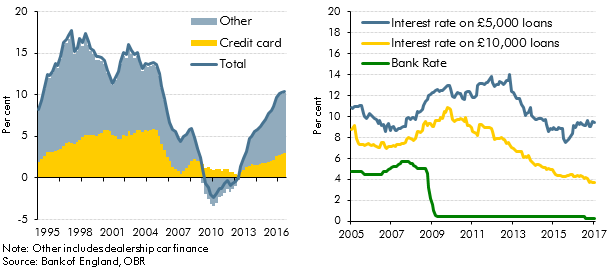

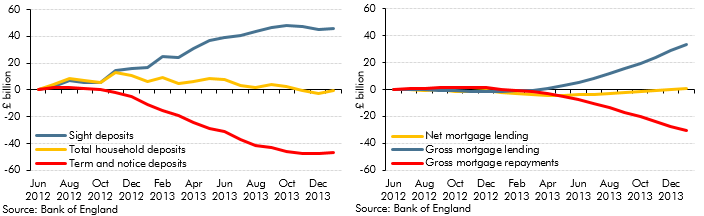

Strong growth in consumer credit in the run-up to our March 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook had prompted concerns among some commentators about its sustainability. In this box we considered the drivers of consumer credit growth, including the role of dealership car finance, and the extent to which it may have supported household consumption growth.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2017 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast for the effects of reducing the ‘personal injury discount rate’.