Covid-19 caused dramatic changes in people's behaviour, which affected where, what and how much economic activity took place. In this box we examined the changes which appeared likely to outlast the pandemic, and the progress the economy had made in adjusting to them.

This box is based on ONS and Springboard data from October and September 2021 .

The successful rollout of highly effective vaccines, coupled with unprecedented fiscal support to households and businesses, has significantly reduced the collateral economic damage that could have resulted from the pandemic. However, coronavirus has also catalysed or accelerated a set of behavioural changes whose consequences may outlast the pandemic itself:

- The pandemic has prompted a sharp rise in the number of people regularly working from home, which rose from 12 per cent before the pandemic to a peak of 50 per cent in April 2020. Despite then falling back, it remained at 31 per cent in October. Moreover, 85 per cent of those who worked from home in May 2021 expected to continue to do so for at least part of the week even after they are able to return to their usual workplace, while in a more recent survey from October, 16 per cent of businesses intended to use increased homeworking as a permanent business model going forward.a

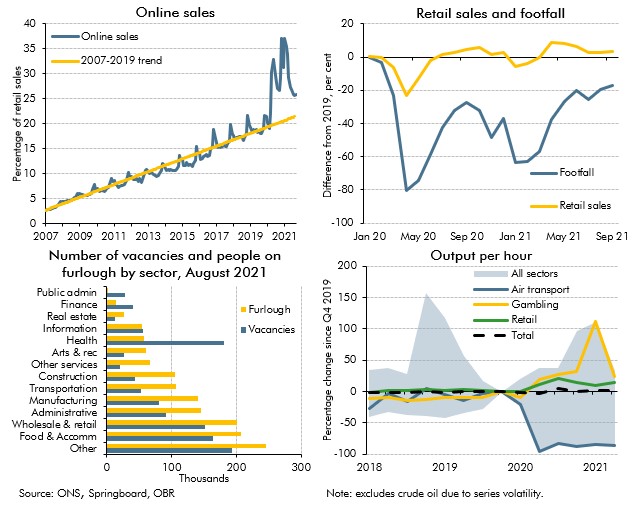

- The pandemic has accelerated the shift in the share of households’ retail spending taking place online. The share rose from below 3 per cent in 2006 to 20 per cent on the eve of the pandemic in 2019, then leapt to a peak of 37 per cent in January 2021. Despite the lifting of most restrictions on retail shops in mid-April, it remained above its pre-crisis trend at around 26 per cent in September (top-left panel of Chart A). A February 2021 survey found that 38 per cent of UK consumers said they will shop more online for products previously bought in stores.b

- The pandemic has seen a sharp reversal in the growth in international air travel. Having risen over three-fold between 1990 and 2019, UK international air passenger traffic fell by 86 per cent to three million a month on average from March to December 2020, compared to the same period in 2019, and remained 48 per cent below its 2019 level in August 2021. Airline analysts predict only a slow recovery in passenger numbers, with global air traffic not expected to return to 2019 levels until 2024.c The profitable business travel area may be more persistently affected: in a May 2021 survey of large global businesses, 72 per cent expected to maintain limits on business travel after social distancing measures end.d

- Both the pandemic and Brexit have prompted firms to consider building greater resilience into their supply chains, reversing a decades-long trend toward internationalisation of production and ‘just-in-time’ logistics. Having risen from 24 per cent in 1965 to 63 per cent in 2018, the trade intensity of UK output has fallen to a twelve-year low of 55 per cent in the second quarter of 2021. A survey of 353 companies across 77 countries found that, post-pandemic, two thirds of businesses were planning to source more locally and 20 per cent planned to hold more inventories.e

These behavioural changes, which surveys suggest will at least partially endure, have had a significant impact on the geographical distribution and sectoral composition of economic activity:

- Geographic distribution. Footfall in retail destinations across the UK was still 17 per cent below pre-pandemic levels in September, though retail sales were up 3 per cent in September, as visitors spend more per visit and sales have shifted online (top-right panel of Chart A). And since the start of the pandemic, house prices have risen 6 percentage points faster in the UK as a whole than in London, and over 3 percentage points faster for detached and semi-detached houses than flats, reflecting the ‘race for space’ as more people work from home.

- Sectoral composition. While total output was only 1.1 per cent below its pre-pandemic level in August, output in the transport sector was still down 9.1 per cent, and other services (including hairdressing and beauty treatments) down 18.7 per cent, while IT and communications output was up 3.1 per cent and health and social work was up 9.8 per cent on pre-pandemic levels.

Chart A: The impact on sectors from the behavioural legacy of the pandemic

Moreover, there are signs that some further adjustment to the composition and location of output and employment may be necessary to respond to these changes. In particular:

- Sectoral mismatch. Comparisons between the sectoral composition of the 1.3 million employees remaining on the furlough scheme in August (its penultimate month) and the 1.1 million vacancies posted in August suggest there may be some supply-demand mismatches in the labour market – especially in retail, transport, and food services (where furloughed staff exceed vacancies) and in health (where vacancies exceed furloughed staff) (bottom-left panel of Chart A). Further, the adoption of new modes of delivery of goods and services induced by the pandemic, for example in the retail sector, will necessitate a significant amount of reallocation within, as well as between, sectors.f

- Geographic mismatch. There is some evidence of geographic mismatch in the labour market, as online vacancies have risen fastest in the North East and Midlands since the start of the pandemic, while increases in unemployment and use of furlough have been most pronounced in London and the South East, which in turn have seen a smaller increase in vacancies.

- Productivity dispersion. Trends in productivity by sector highlight large and persistent differentials in output per hour worked (bottom-right panel of Chart A) – driven mainly by

underperformance in those sectors with relatively high fixed costs and/or greater exposure to the potential behavioural legacies of the pandemic, such as air and water transport,

and other services. The withdrawal of government support for these sectors could warrant a transition to new business models, involving reallocation of factor inputs, unless demand in these sectors makes a complete recovery. By contrast, in some sectors, such as retail, the pandemic has encouraged new approaches resulting in improved productivity. If businesses seek to hold on to these improvements, some of the changes to their business models will endure with potential consequences for their demand for labour.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2021