The tax gap is the difference between taxes collected by HMRC and the theoretical liability, or what, in theory, should be collected. As a share of GDP, it has reduced from 2.3 per cent in 2005-06 to 1.5 per cent in 2021-22, two-thirds of which is explained by reductions in the VAT gap. In this box, we explored the recent drivers of changes in tax gaps, explained what assumptions we make about tax gaps in our forecast and outlined the associated uncertainties.

This box is based on HMRC data from June 2023 .

The tax gap is the difference between tax collected and total theoretical tax liabilities (the amount of tax that should, in theory, be collected if individuals and businesses paid all tax due).a In 2021-22, HMRC estimated the tax gap to be £35.8 billion, or 4.8 per cent of total theoretical tax liabilities (equivalent to 1.5 per cent of GDP), meaning that HMRC collected 95.2 per cent of all tax due. Changes in the tax gap represent a risk to our forecast: all else equal, a smaller tax gap will increase receipts, whereas a higher gap reduces receipts. This box explores how the tax gap has evolved since 2005-06, the main drivers of the changes, the assumptions we make about the tax gap in our forecast, and the associated uncertainties.

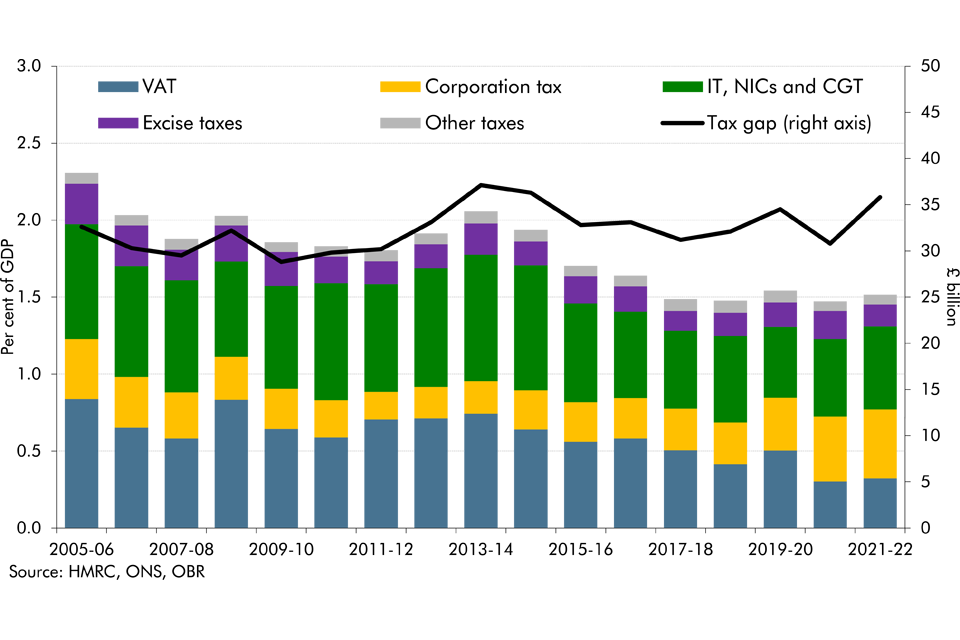

As shown in Chart A, as a share of GDP the tax gap fell from 2.3 per cent in 2005-06 to 1.5 per cent in 2021-22 (equivalent to a fall from 7.5 per cent to 4.8 per cent of tax liabilities). The main drivers of this reduction were:

- The VAT gap has reduced from 0.8 per cent of GDP in 2005-06 to 0.3 per cent in 2021-22 (equivalent to a fall from 14.0 per cent to 5.4 per cent of tax liabilities), explaining about two-thirds of the reduction in the overall tax gap. Much of this fall has occurred since 2013-14. HMRC have introduced several measures in recent years aimed at closing the VAT gap, and the reduction in the use of cash, especially since the pandemic, is also likely to have contributed.

- The tax gap related to personal income taxes has reduced from 0.7 per cent of GDP in 2005-06 to 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2021-22 (the equivalent of 4.5 per cent and 3.0 per cent of tax liabilities, respectively), which is likely to reflect HMRC activity to drive better compliance around business payroll. There has also been a reduction in the excise tax gap from 0.3 per cent of GDP in 2005-06 to 0.1 per cent in 2021-22 (the equivalent of a fall from 8.3 per cent to 6.1 per cent of tax liabilities).

- The corporation tax gap has increased from a low of 0.2 per cent of GDP in 2011-12 to 0.4 per cent in 2021-22 driven by the small business corporation tax gap, which increased from 8.8 per cent of tax liabilities in 2011-12 to 29.3 per cent of tax liabilities in 2021-22. The tax gap (across all taxes) attributable to small businesses has increased to 56 per cent of the overall tax gap in 2021-22. Aiming to address this, HMRC has introduced new small business support activity and in March 2023 announced a review of small business guidance and forms.

Chart A: Tax gap as a share of GDP

Comparisons with other countries are difficult because of limited availability of data and methodological differences, but where these are available the UK generally compares favourably. National Audit Office reporting of tax gaps from the US, Canada, Australia and Italy between 2011 and 2016 ranged from 7.4 to 19 per cent of tax liabilities, compared to between 5.5 and 7.0 per cent of tax liabilities in the UK during the same period.b

In our baseline forecast we assume that the tax gap remains flat as a proportion of tax liabilities. This is consistent with the broadly flat overall trend seen since 2017-18. There are upside and downside risks to this assumption. Factors such as the ongoing digitalisation of the tax collection system and a further reduction in the use of cash in the economy could push down on the tax gap. On the other hand, subdued economic growth and cost of living pressures could lead to wider non-compliance. We do adjust our baseline forecast to account for specific measures directly targeted at reducing the tax gap. We scrutinise such measures to ensure the estimated yield is reasonable and accounts for behavioural responses, for example that some individuals or businesses will find alternative ways to avoid complying with new measures. As an illustration of the risk to our forecast, if the tax gap, as a share of GDP, fell by a further 0.3 per cent, roughly half of the decrease in the four years between 2013-14 and 2017-18, that would increase receipts by £8.4 billion a year, on average.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2024

a The tax gap estimates only cover the taxes administered by HMRC, so they exclude any taxes and duties administered elsewhere, such as council tax, business rates and vehicle excise duty, as well as charges such as the congestion charge.

b In Tackling the tax gap the NAO notes that these figures are not always directly comparable due to the different measurement methods and tax regimes included.