We updated our July 2013 analysis of fiscal drag on income tax and NICs to reflect new data, our latest assumptions and the effect of measures announced over the past year. This box outlined how fiscal drag effects income tax and NICs receipts and the long-term assumptions used.

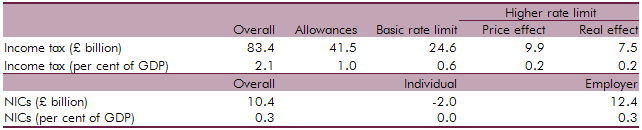

We have updated last year’s analysis of fiscal drag on income tax and NICs liabilities between 2019-20 and 2033-34. The analysis is based on the latest Survey of Personal Incomes, our latest long-term economic assumptions and the effect of measures announced over the past year such as the increase in the personal allowance. Table A shows that by 2033-34 fiscal drag would increase tax revenues by 2.1 per cent of GDP if tax thresholds and allowances were raised in line with inflation. As was the case last year:

- around half comes from people moving into paying tax and some taxpayers paying a higher proportion of their income at the basic rate;

- around a third comes from taxpayers moving into the higher rate band, and people paying the higher rate on a larger proportion of their income; and

- the remaining portion comes from the additional rate threshold and the personal allowance taper. The medium-term assumption is that these are fixed in cash terms, so there is fiscal drag relative to CPI inflation on top of the normal fiscal drag relative to incomes.

The effect on NICs is much smaller, as the marginal rate for employee NICs falls to 2 per cent on earnings above the upper earnings limit. Continued fiscal drag would therefore lead to lower receipts from employee NICs, offset by higher employer NICs where there is no upper limit.

Table A: Effect of fiscal drag on income tax and NICs receipts by 2033-34

Our long-term assumptions for uprating pensioner benefits are similar to the current medium-term policy settings. In both cases the basic state pension is subject to the ‘triple lock’ (rising by the maximum of earnings, prices or 2.5 per cent a year), and pension credit is uprated with earnings. The second state pension is uprated by CPI in payment, but earnings in accruals. The single-tier pension is legislated to rise at least in line with earnings. For the purposes of these projections, we assume it is also subject to the ‘triple lock’, which raises spending by 0.2 per cent of GDP by 2033-34.

Over the medium term, other smaller pension benefits and non-pension benefits to pensioners, including disability benefits, are due to be raised in line with inflation. If we assumed that this remained the case over the longer term then these would be 0.3 per cent of GDP lower in 2033-34 than under our central assumption that they rise in line with earnings.

Nearly all working-age benefits are due to be uprated by CPI in the final year of our medium-term forecast. Maintaining this over the longer term would reduce spending on these benefits by 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2033-34 relative to our central assumption of earnings uprating.