The Government carried out a number of reforms to the student finance support system, shifting funding from direct grants to loans to students. This box looked at the impact of student loans on public sector net debt.

This box is based on OBR data from July 2011 .

This box looks at the impact on public sector net debt of the current student finance support system in England for full-time students. This is based on Department of Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) projections for loans and repayments out to 2060, based on a number of stylised assumptions and the OBR’s long-term economic assumptions.

Over recent years successive governments have increased the fees that students can be charged for higher education, so shifting the funding of the system from direct grants to loans to students. Student loans are classified as a financial transaction so they are not included in net borrowing. But they are included in the government’s cash requirement in any year and add to the stock of government debt.

Our analysis shows that this increase in debt is expected to peak in the 2030s and then decline as loan repayments rise relative to the value of new loans. BIS calculate that the design of the student loan system is such that around 30 per cent (in net present value terms) of the overall cost to the government of issuing and financing the loans will not be repaid over the maximum 30 year repayment period.

There are three key assumptions needed to make these projections: the average tuition fee loan, the take-up rate of the loans and student numbers. Currently, the reaction of both universities and prospective students to the recent reforms is particularly uncertain:

- student numbers: are assumed to be flat at their current level. Because of a decline in the student age population over the next decade, this implies a rise in the higher education participation rate. The extent to which higher tuition fees discourage students from attending university remains the key uncertainty. There is currently excess demand for places, but if there was a big effect on participation from higher fees, it is possible that universities would need to reconsider fee levels to maintain demand;

- the average tuition fee loan: we have kept the assumption used in the March forecast of an average tuition fee of £7,500 in 2012-13. Since March, many universities have announced their intention to charge a headline rate of £9,000. However, they still need to have access agreements approved by the Office of Fair Access (OFFA) to charge above £6,000. Also it is not clear by how much fee waivers and bursaries will reduce the headline figure, and whether students will take out the maximum loan available to them. We will revise the average tuition fee estimate on the basis of additional information which will become available later in the year; and

- the loan take-up rate: around 90 per cent of students are assumed to take up loans, a slight rise from the current level. Higher fee rates would suggest that more students will need a loan, but the introduction of a real interest rate on the loan could discourage take-up.

The Government has not set a long term policy for the uprating of the tuition fee cap and maintenance loans and grants from 2013-14. The medium-term forecast assumes these are uprated by inflation from 2013-14 to 2015-16. In our long-term projection we make the assumption that the cap is uprated by earnings growth from 2016-17. If we assumed that the cap was raised by inflation over the long term, then university income would steadily diminish relative to the size of the economy.

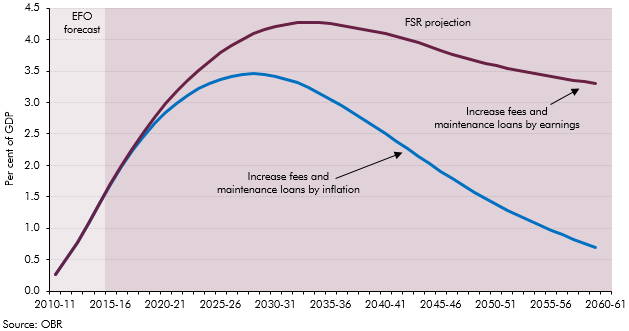

Chart A: Addition to public sector net debt due to student loans

Chart A looks at the impact on public sector net debt with the cap uprated by both earnings and prices. With loans being issued upfront, but repaid over a prolonged period, net debt as a proportion of GDP rises in the initial years of the projection. With tuition fees rising by inflation each year, the impact on net debt from student loans peaks in around 2030 at 3.4 per cent of GDP (£50bn in today’s terms) and then falls away. With tuition fees rising by earnings, the higher value of loans being issued means that the impact would peak at 4.3 per cent of GDP (£63bn in today’s terms). Assuming an average fee loan of £8,000, rather than £7,500, would raise the peak impact on net debt by only around 0.2 per cent of GDP (£3bn in today’s terms).

Over the longer term, the impact of the reform on net debt would diminish as more repayments come in. By the end of our projection horizon in 2060-61, the net addition to public sector net debt with our central assumption of earnings uprating is 3.3 per cent of GDP (£49bn in today’s terms). With fees and loans linked to inflation it would be 0.7 per cent of GDP (£10bn in today’s terms).