On 7 September 2021, the government announced a reform to the funding of adult social care in England. In this box, we described how this reform compares with the 2011 Dilnot Commission proposals and the reforms from the Care Act 2014 that were planned for April 2016 and then abandoned.

This box is based on OBR and DHSC data from October 2021 .

On 7 September 2021, the Government announced a package of reforms to the funding of social care, including a cap on the amount that anyone in England has to spend on adult social care over their lifetime. The cap will be set at £86,000 and take effect from October 2023.a The cap operates in a similar way to that proposed by the Dilnot Commission in 2011, though it is higher than the original £35,000 proposal (around £46,000 in 2023-24 prices).b It is, however, similar (after accounting for inflation) to the £72,000 cap set in the Care Act 2014, which was meant to apply from April 2016 but was dropped before it had been implemented.c

The reforms also include a means-test on local authority contributions to care costs for individuals with assets below £100,000 (known as the ‘upper capital limit’), with no requirement to contribute to costs at all for those with assets below £20,000 (the ‘lower capital limit’). This is a large increase relative to the current system, in which the lower and upper capital limits are £14,250 and £23,250 respectively,d but the reforms retain the single upper capital limit structure already in place. By contrast, the 2014 reform would have introduced a differential system, with upper capital limits set at £27,000 (£32,000 in 2023-24 prices) for those in domiciliary care and £118,000 (£139,000 in 2023-24 prices) for those in residential care.

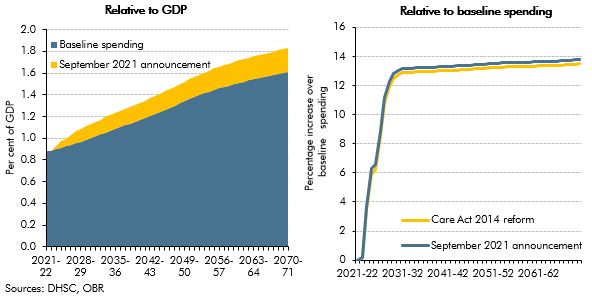

Our 2013 and 2018 Fiscal sustainability reports showed how the costs of these reforms rise steadily over the longer term. They start relatively low because few individuals reach the lifetime costs cap in the initial years of implementation. It takes several years for the system to reach steady state in terms of numbers of people having their costs covered by the state. The left panel of Chart A presents a provisional long-term profile of the cost of the latest reforms relative to a baseline long-term projection of social care spending, which suggests these reforms will cost around ¼ per cent of GDP a year in the long term, little changed from the 2014 reform.

At the margin, the September 2021 announcement is slightly more expensive than the 2014 reform, adding 13.8 per cent to baseline spending in steady state, compared to 13.5 per cent under the 2014 Act (right-hand panel of Chart A). This is due to the single upper capital limit, which entails slightly more people being entitled to means-tested support (and people with modest assets above the limit receiving means-tested support at an earlier point of asset depletion). But there are still some details of the reforms to be finalised, and so we will consider their long-term implications more closely in our next Fiscal sustainability report.

Chart A: Long-term cost estimate of social care funding reforms as a share of GDP and relative to baseline spending

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2021