The level and nature of inflation has consequences for the public finances. This box explored the fiscal consequences of the sharp rise in inflation since our March 2021 forecast and examined the fiscal effects of the two scenarios described in Box 2.6 in our October 2021 EFO one where inflation is driven mainly by pressures in the product market, and the other mainly pressures in the labour market. The box concluded the labour market inflation scenario was significantly more beneficial for the public finances.

This box is based on OBR data from October 2021 .

Historically, bouts of unanticipated inflation have benefited the public finances, allowing successive governments to ‘inflate away’ much of the debt from World War 2. In our 2021 Fiscal risks report we showed that this historical experience may no longer be a good guide to the effect of higher inflation on the public finances today. This is because inflation raises the cost of servicing the government’s large stock of index-linked gilts, which has grown from nothing in 1980 to 24 per cent of all gilts in 2020-21. Assuming that higher inflation is associated with higher nominal interest rates, it also feeds through rapidly to the cost of central bank reserves, which have risen to 38 per cent of GDP over the past 13 years to finance the Bank of England’s quantitative easing. An inflation shock now feeds quickly into the cost of these instruments: instantly in the case of index-linked gilts and as Bank Rate is increased to bring inflation back to target in the case of central bank reserves. But it remains the case that the fiscal consequences of higher inflation depend crucially on the source of that inflation – imported inflation that reduces real wages is fiscally costly; domestically generated inflation driven by rising wages is beneficial.

The direct effect of higher inflation on our latest forecast

Inflation has picked up sharply this year. We have revised up our near-term forecasts materially since March. CPI inflation, which features in many parts of the tax and spending systems, now peaks at 4.4 per cent in the second quarter of 2022, rather than rising steadily back to the 2 per cent target from below it. RPI inflation, which determines the cost of servicing index-linked gilts, reaches 5.4 per cent in the first and second quarters of 2022. In terms of the price level, which determines the medium-term fiscal consequences of inflation on the public finances, CPI has been revised up by 3.8 per cent in 2025-26 relative to March, and RPI by 4.9 per cent.

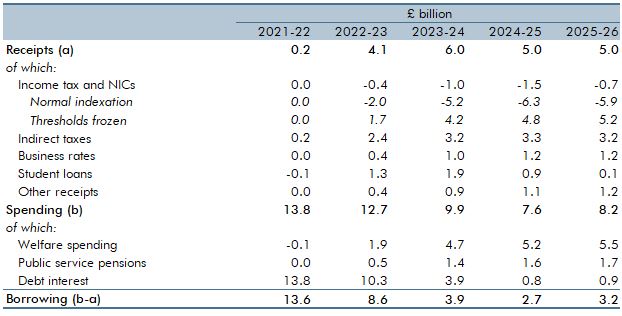

In isolation, these developments have raised borrowing, particularly in 2021-22 and 2022-23. The channels along which they manifest can be split into four groups:

- Income tax and NICs. On its own, inflation reduces income tax and NICs receipts by raising thresholds in the tax system and thereby reducing fiscal drag (where more income is taxed at higher rates as wages rise relative to thresholds). In normal circumstances, higher inflation would have reduced receipts by around £6 billion a year by 2025-26 relative to our March forecast. But in this forecast that is almost entirely offset by the March 2021 Budget threshold freezes raising correspondingly more than expected. Coupled with higher wage growth and other factors, our pre-measures income tax and NICs forecast in 2025-26 has been revised up £27.6 billion, illustrating the importance of understanding the interaction between the economic context and policy developments.

- Other taxes and accrued interest on student loans. For most excise duties, business rates, and interest on student loans, CPI or RPI determines the tax rate or interest rate charges.

Higher inflation since March adds £5.7 billion to these receipts in 2025-26. - Debt interest. With nearly £500 billion of index-linked gilts outstanding, higher near-term RPI inflation has added £13.8 billion to spending in 2021-22 and £10.3 billion in 2022-

23. The upward revisions diminish quickly thereafter as inflation subsides. - Welfare spending and public service pensions. Most working-age welfare payments and public service pensions in payment are linked to CPI inflation. Spending on these items is therefore ultimately linked to the price level, the upward revision to which has added £7.3 billion a year to spending by 2025-26.

Table A: Direct effects of higher inflation on borrowing since March

Alternative inflation scenarios

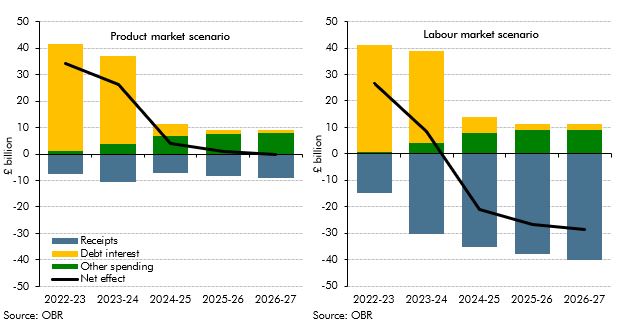

In Box 2.6 we set out two alternative inflation scenarios. In each, inflation is both higher and more persistent, but the underlying drivers differ. As a result, their fiscal consequences differ too:

- In the product market scenario (shown in the left-hand panel of Chart B), cost-driveninflation requires materially higher interest rates to return inflation to target, but with limited pass-through into higher wages and consumption (and therefore income tax, NICs, and VAT). This leaves borrowing higher in the short term thanks to higher debt interest spending (due to both higher Bank Rate and higher inflation). Welfare spending also rises materially. But as the initial inflation and associated Bank Rate rises pass, the debt interest impact falls away. By the end of the scenario, higher receipts almost exactly offset higher spending with no net effect on borrowing.

- In the labour market scenario (shown in the right-hand panel of Chart B), higher inflation is driven by stronger wage growth, raising both the price level and the labour share of national income. This lowers borrowing significantly over the medium term. While spending is broadly in line with the product market scenario, income tax and NICs receipts are much stronger thanks to higher wages. This feeds through into higher consumption (boosting VAT and excise duties) and higher houses prices (boosting stamp duty and CGT receipts). By the end of the scenario, higher receipts more than offset higher spending and borrowing is almost £30 billion lower.

These scenarios illustrate the importance of considering the underlying drivers of any economic news when assessing its likely fiscal consequences. For now, the energy and supply bottleneck-driven burst of inflation underway looks more like the product than the labour market scenario, entailing a net increase in pressures on the public finances in the near term. However, if this inflation pressure feeds through into wages, consumption, and house prices, on unchanged policies this could provide some offsetting benefit to the public finances in the medium term.

Chart B: Public sector net borrowing effects of our alternative inflation scenarios

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2021