Between March 2021 and November 2022, almost all the main allowances and thresholds in income tax and national insurance contributions (NICs) were frozen rather than indexed to inflation, as is the default in nearly all cases, up to and including 2027-28. The Chancellor has subsequently announced personal tax cuts that are due to offset around a half of the resulting impact on the personal tax burden by 2028-29. In this box, we showed estimates for total effects of these policy decisions on work incentives, given high inflation, over the period from 2021-22 to 2028-29.

This box is based on OBR data from March 2024 .

Between March 2021 and November 2022, almost all the main allowances and thresholds in income tax and national insurance contributions (NICs) were frozen rather than indexed to inflation, as is the default in nearly all cases, up to and including 2027-28. The Chancellor has subsequently announced personal tax cuts that are due to offset around a half of the resulting impact on the personal tax burden by 2028-29. Since March 2021, the main policy changes have been:

- Freezing key income tax thresholds: the personal allowance (PA) and higher rate threshold (HRT) at £12,570 and £50,270 from 2022-23 to 2027-28.

- Lowering the additional rate threshold (ART) from £150,000 to £125,140, from April 2023, to align it with the PA taper.

- Various other changes to thresholds and allowances: the increase in the NICs primary threshold and lower profits limit to align with the PA and then freezing both to 2027-28. The NICs upper earnings limit, upper profits limit and employer secondary threshold were also frozen to 2027-28.

- November 2023 NICs cuts: a 2 percentage point cut in the main rate of employee NICs (effective from 6 January), a 1 percentage point cut in the main rate of NICs for the self-employed, and the removal of the requirement to pay Class 2 NICs (both effective from 6 April) announced in the Autumn Statement.

- March 2024 NICs cuts: a further 2 percentage point cut in the main rate of both employee and self-employed NICs (from 6 April) announced in this Budget.

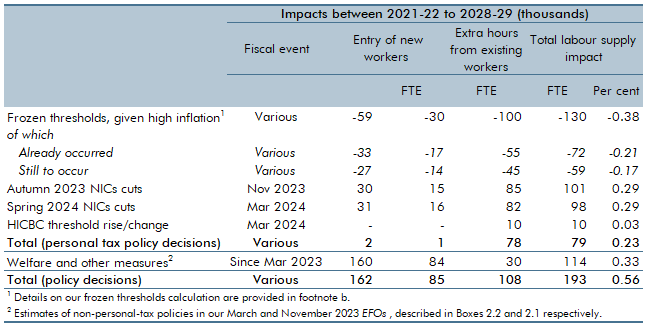

Table A shows our estimates for total effects of these policy decisions on work incentives, given high inflation, over the period from 2021-22 to 2028-29.a Some of these effects have already occurred while others will continue over the forecast period. The policies have both positive and negative effects on work incentives. But their net effect is to increase labour supply by an estimated 79,000 in full-time equivalent (FTE) terms (0.2 per cent) by 2028-29. Almost all of the increase comes from existing workers choosing to work longer hours (78,000 FTE), while the net impact from additional employment is 1,000 FTE. Including the impact of the government’s recent childcare expansion and welfare reforms, we estimate the overall net increase in total labour supply by 2028-29 is 193,000 people in full-time equivalent terms.

Table A: Labour supply impacts of major personal tax policies

Looking at the labour supply impacts of each of these policies in turn:

- Fiscal drag from frozen thresholds given high inflation will directly affect the work incentives of the 39 million taxpayers that will earn above the personal allowance by 2028-29. But the effect is driven by the 7 million subset of workers that will be newly taken into tax or into higher tax brackets, and so reduce their hours in response to facing significantly higher marginal tax rates than would otherwise be the case. This decreases labour supply by an estimated 130,000 in FTE terms by 2028-29, relative to a counterfactual in which thresholds rose in line with inflation from 2022-23 to the values shown in Table 3.6.b We judge that 55 per cent of this impact has already occurred, so the effect over our forecast period is less than half the total, whereas the positive NICs cuts’ effects are all to come.

- The cuts to NICs announced in this Budget change the work incentives of the 28 million employees and 2 million self-employed individuals that currently earn between the primary threshold and upper earnings / profits limit. As described above, this operates in a similar way to November’s announcement, generating a labour supply impact of 98,000 in FTE terms, with a combined impact across both measures of 199,000 FTEs.c

- The HICBC reform has very large effects on marginal post-tax earnings, but for relatively small numbers of people. The main beneficiaries are the 170,000 individuals with a lead household income between £50,000 and £60,000. As described above, this measure boosts labour supply by 10,000 in FTE terms.

Focusing just on the most recent tax changes (the November NICs cuts, the NICs cuts in this Budget and the changes to the HICBC), whose effects will be felt over the next five years, plus the remaining impact of the frozen tax thresholds, the net impact from now to 2028-29 is a positive 150,000 FTE workers.

These estimates are subject to considerable uncertainty, as are those for the welfare, childcare, and other measures announced in the last two fiscal events (as discussed in Box 2.1) that increase labour supply by 114,000 in FTE terms. These sources of uncertainty include:

- The responsiveness of individuals in different demographic subgroups and income bands to changes in financial incentives. Plausible alternate assumptions for the elasticities used in our modelling could substantially impact our estimates.

- Another source of uncertainty relates to our underlying economy forecast. This forecast reflects the increase in the size of the workforce that is implied by the latest labour force and population projection releases. As a result we have increased our previous estimate of the impact of the November 2023 NICs cuts from 94,000 to 101,000. Deteriorating economic conditions could also reduce our estimates, for instance, if spare capacity opens up over the coming years as labour demand fails to match supply.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2024

a These are derived by inputting our own assumptions about elasticities and other parameters into the Treasury’s labour supply model to assess the impacts of personal tax policy changes on work incentives. For further details on the methodology, see OBR, The labour supply effects of the Autumn 2023 National Insurance Contributions cut, February 2024.

b We use lagged, third-quarter CPI as a close proxy for the previous year’s September CPI figure with which most thresholds are uprated. This therefore essentially reflects the impact of not raising all the thresholds shown in Table A with inflation, as well as leaving frozen some thresholds that have been fixed for a longer period, like the Personal Allowance Taper. For the Additional Rate Threshold (ART) of Income Tax, which was lowered from £150,000 to £125,140 in 2023-24, we started assuming divergence from the counterfactual from that point, to focus on the impact of decisions to freeze tax thresholds (or, in some cases, implicit decisions to leave them frozen), and avoid conflation with other contemporaneous policy changes. We have adjusted changes in non-devolved taxes to the UK level by simple scaling, abstracting from some small differences in uprating policy in Scotland.

c As described below, we have made an upward adjustment to the labour supply effect estimate of the November 2023 NICs cut.