This box discussed the risks to our medium-term forecast of day-to-day departmental (RDEL) spending, particularly in relation to the impact of the pandemic.

This box is based on HM Treasury and OBR data from .

The remit set for the OBR by Parliament requires us to base our forecasts on the current policy of the Government, and not to consider alternative policies. But we are also tasked with producing a central forecast and assessing risks to that forecast. One of the most significant risks to the medium-term fiscal outlook relates to the potential legacy of the pandemic for spending on public services. The huge sums allocated to fight the virus mean that departmental resource spending (RDEL) is expected to have risen by 36 per cent or £122 billion in 2020-21. However, only £56 billion (equivalent to a 15 per cent increase on pre-pandemic RDEL plans) has been added to fund virus-related activities in 2021-22 and no provision for virus-related spending has been added to pre-pandemic plans thereafter. As a result, RDEL spending rises from 14.4 to 21.2 per cent of GDP in 2020-21, but then falls back to 15.3 per cent of GDP in 2022-23. The resulting increase between 2019-20 and 2022-23 is a slightly smaller rise than the Government had planned in its pre-pandemic Budget in March 2020.

Historical experience suggests that it is easier to increase public spending during a crisis than it is to reduce it once the crisis has abated. RDEL rose from 16.3 to 18.3 per cent of GDP during the two peak years of the financial crisis in 2009-10, but fell back by only half as much, to 17.2 per cent, over the subsequent two. Overall public spending five years after the first and second world wars was respectively 11 and 9 per cent of GDP higher than it had been on the eve of those conflicts, with the tax-to-GDP ratio also significantly higher to pay for a state whose scope of activities had significantly expanded.

Given this context, this box considers the potential upward pressures that could impinge upon RDEL spending in the 2021 Spending Review and beyond. These pressures come from a combination of the direct legacy costs of the pandemic itself on public services, the backlog of non-virus-related public service activities that have been postponed as a result of the pandemic, and the wider economic disruption brought about by coronavirus. Several of these likely future pressures were discussed in the Government’s Roadmap out of the pandemic.a

The extent to which any additional spending in these areas leads to higher RDEL spending overall would depend on choices made at future Spending Reviews. The Government might, for example, choose to allocate less than it otherwise would have done to its pre-pandemic priorities given the changed circumstances. And if the Government did choose to increase overall RDEL spending to accommodate higher spending in some areas without reducing it in others, the extent to which it would represent a risk to medium-term borrowing would depend on choices about cuts to other spending and/or further tax rises.

The most direct virus-related costs that could persist longer than currently factored into the Government’s plans are the direct health costs of coronavirus. So long as the virus continues to

circulate in the UK, there could be ongoing costs from NHS Test and Trace, which have been running at several billion pounds a month so far this year. Similarly, the Government noted in the Roadmap that “vaccinations – including revaccination… is likely to become a regular part of managing COVID-19”. There could also be greater-than-assumed medium-term implications for spending as a result of ‘long Covid’ cases and the consequences for mental health arising from the pandemic and the lockdowns. The Health Foundation estimates that just the mental ill-health legacy of the pandemic could cost at least £1 billion a year over the next few years.b

In addition to these direct demands on the health service, the Government stated in the Roadmap that it is “committed to building resilience for any future pandemics, both domestically and on the international stage.” This could require building greater spare capacity in the health service so that it is more resilient to sudden surges in demand of the type experienced over the past year. The OECD reports that, internationally, the UK entered the pandemic with relatively high levels of bed occupancy and relatively low average per capita numbers of critical care beds.c The NHS estate might also need to be reconfigured so that managing large numbers of infectious patients and segregating them from the non-infected population does not routinely disrupt other treatments – something that is made more challenging in the UK by the relatively old NHS hospital estate.d The Health Foundation notes that continued social distancing and infection control measures could reduce NHS productivity relative to pre-crisis assumptions, calculating that every percentage point of productivity lost could generate £1.4 to £1.7 billion a year of spending pressure.e

In addition to these virus-related pressures, there are likely to be costs associated with clearing the backlog of non-virus-related activity in the NHS. Between April and December 2020, there were 5.3 million fewer referrals for hospital care in England than over the same period in 2019. At least some of these people not seen last year will need treatment eventually, which can be expected to add to the 4.5 million already on a waiting list for NHS care. Waiting times have already risen: the latest figures show that 224,000 people have been on NHS waiting lists for more than a year, compared to just over 1,500 a year ago.f In November, the Health Foundation estimated that clearing the backlogs and reducing waiting times would cost around £2 billion a year over the next three years, but also warned that the level of increased activity required to do so might not be achievable due to staffing constraints.b

The Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC’s) ‘core’ non-virus budget in 2021-22 was set at £147.1 billion in the last Spending Review. While an additional £50.1 billion was added in 2020-21 and £20.3 billion was added in 2021-22, no additional resources beyond those in its multi-year settlement have been provided to deal with the above pressures in future years.

While the health service faces the most direct set of costs from the legacy of the pandemic, the events of the past year could also generate spending pressures in other areas:

- Social care. The pandemic hit the old-age social care sector particularly hard. The combination of additional future pressures and the high proportion of coronavirus deaths that have occurred in care homes is likely to increase pressure on the Government to deliver the funding reform that it committed to in its 2019 Manifesto. In May 2020, the House of Lords Economic Affairs committee wrote to the Chancellor proposing a funding model that the Health Foundation and King’s Fund have estimated would cost an additional £7 billion a year.g In his response, the Chancellor noted that this proposal came “at a time when the vital work done by the sector is at the forefront of the public’s minds” and committed to “bring forward a plan for social care for the longer term.”h

- Education. The closure of schools for significant periods of the past year has significantly reduced the number of teaching hours received by the current cohort of school-aged children. The Prime Minister has stated that “no child will be left behind as a result of the pandemic” and an intention to “develop a long-term plan to make sure pupils have the chance to make up their learning over the course of this Parliament.”i The Roadmap highlights “studies suggesting the total loss in face-to-face learning could amount to around half a school year” and states that an Education Recovery Commissioner has been appointed “to oversee a comprehensive programme of recovery aimed at young people who have lost out on learning due to the pandemic”. In three successive announcements since the start of the pandemic, the Government has committed to an additional £1.7 billion to funding catch-up schooling in England. This includes £0.4 billion in this Budget, which has been allocated from the 2021-22 Covid reserve that was set aside at the Spending Review.

- Local authorities. Central government support for local authorities makes up £7 billion of the overall cost of virus-related measures the Government has announced so far. Since the start of the pandemic, one local authority has issued a ‘Section 114 notice’ (in effect, declaring itself bankrupt), while five have received special access to borrowing to cover day-to-day spending in this Budget. There is potential for further significant calls on central government to maintain local services in some scenarios.

- Transport. The pandemic has also significantly disrupted domestic and international transport and generated calls for substantial and lasting fiscal support. The Government has already intervened this year with direct support to the railways and to Transport for London at a cost of £12.8 billion. With restrictions on international travel and new quarantine measures in place, the Government may also face calls for support from airports, airlines, and other transport providers.

Because of the Government’s decision to suspend multi-year budget planning and revert to annual spending rounds for most departments, whether and how the Government plans to respond to these pressures is not yet known. However, since the start of the pandemic, the Government has actually reduced planned RDEL spending in 2022-23 by £14.3 billion (0.6 per cent of GDP) rising to £16.5 billion (0.6 per cent of GDP) relative to the totals that it set out in Budget 2020. That includes cuts to plans announced in this Budget ranging from £3.3 billion in 2022-23 up to £3.9 billion in 2025-26 (described in paragraph 3.78).

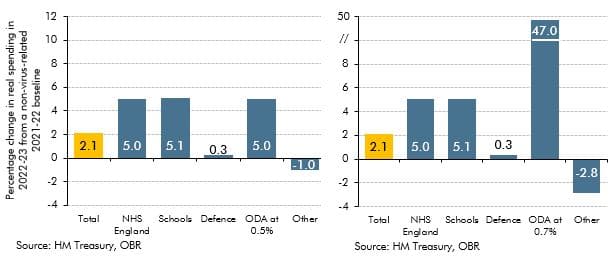

This implies increasingly tight budgets for non-protected departments (i.e. those outside health, education, defence and overseas aid) going into the next Spending Review this autumn, especially given the Government’s stated intention to return the aid budget to 0.7 per cent of national income “when the fiscal position allows”. As shown in Chart E, even before taking account of any of the legacy pressures of the pandemic discussed above, were the Government to stick to the RDEL totals set out in this Budget while retaining the multi-year settlements made in Spending Review 2020 and keeping aid spending at the 0.5 per cent of national income it was cut to in the Spending Review, RDEL budgets for unprotected departments would need to fall by 1 per cent in real terms between 2021-22 and 2022-23. If it deemed that the aid budget could return to 0.7 per cent of national income, that would require the RDEL budgets of unprotected departments to fall by 2.8 per cent in real terms between 2021-22 and 2022-23.

Chart E: Change in real RDEL spending in 2022-23

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2021