The possibility of a new vaccine-escaping Coronavirus variant cannot be ruled out. In this box we explored the possibility of such an escape and investigated the potential economic and fiscal consequences.

This box is based on OBR data from June 2022 .

The pandemic was the largest shock to the UK economy in a century. While successful vaccines have enabled much of our economic lives to return to normal, the emergence of new vaccine-escaping Covid variants remains a key downside risk. Over the past two years, the UK has seen four major waves of infections caused by different variants, and public health experts have warned that Omicron is unlikely to be the last.a

As of the middle of June, Covid infections in the UK had doubled on a month earlier, albeit from a low base, with the ONS estimating that over 2 per cent of the population had Covid. In common with other European countries, the US and South Africa, this has been caused by the growing prevalence of new Omicron variants (especially BA.4 and BA.5). Thankfully, as yet, deaths remain low though hospitalisations have risen, suggesting current vaccines remain effective in combating serious illness.

However, to illustrate the ongoing economic and fiscal risks associated with the potential emergence of a new, vaccine-escaping variant of covid, our March 2022 EFO included a Covid downside scenario that assumes:

- A new, vaccine-escaping Covid variant emerges in winter 2022-23 with a health impact broadly between the Alpha and Omicron waves.b

- The variant is as contagious as Omicron but causes more severe illness and requires existing vaccines to be adapted, then manufactured and rolled out.

- Adapting vaccines takes three-to-four months with rollout to the majority of the adult population taking another three months.c The first wave of infections peaks before the adapted vaccines can be rolled out, but they help to limit the health impact of the following winter’s second wave.

- A fall in mobility that is broadly between the Alpha and Omicron waves, due to a combination of additional public health restrictions and greater voluntary social distancing, that eases by the end of the first quarter of 2023 as infections fall.

- The GDP impact of this fall in mobility is calibrated to 2021 outturns rather than 2020, to reflect the adaptation of the economy to public health restrictions during the pandemic.d Greater adaptation would further lessen the economic impact.

- Government fiscal support is proportionate to the economic impact of previous waves of infections.

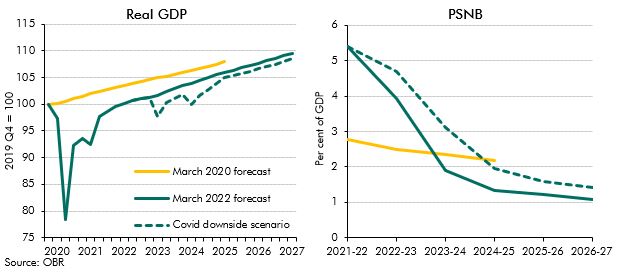

Under these assumptions, GDP falls 3.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2023, then recovers from the second quarter as infections fall and the vaccine is rolled out. The second wave of infections causes GDP to fall by 1.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2024, around half as bad as the first wave. Sectors most affected by previous waves, such as transport, travel and hospitality, drive the fall in GDP. In the medium term, there is an additional 1 percentage point scarring to potential output compared to our central forecast (Chart A). The additional scarring is caused by lower labour supply (for example due to greater long-term sickness) and a larger fall in productivity (for example because firms face further production inefficiencies from continuing to operate under the pandemic).

Chart A: Real GDP and government borrowing in the Covid downside scenario

The scenario increases borrowing by 0.8 per cent of GDP in 2022-23 and by 1.4 per cent of GDP in 2023-24 relative to our central forecast, falling to 0.3 per cent above the central forecast by 2026-27. The effect in 2022-23 is mostly due to the assumption of further discretionary fiscal support that is proportionate to the fall in GDP. Tax receipts move broadly in line with GDP (with some delayed effect due to the time lags in self-assessment payments). But spending as a share of GDP remains higher than our central forecast in every year due to the 1 per cent scarring of nominal GDP, which raises spending as a share of GDP in 2026-27 by 0.4 percentage points. Debt is 3.6 per cent of GDP higher by 2026-27, largely as a result of higher cumulative borrowing, as well as the smaller denominator.

This box was originally published in Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2022