In November 2022 the government reduced its departmental (DEL) spending assumptions for the final three years of the forecast period. This box discussed the implications of the government's day-to-day and capital spending plans for various departments and public services during and after the 2021 Spending Review.

This box is based on HMT data from October 2021 and November 2022 .

Of the Autumn Statement’s £61.7 billion in discretionary fiscal tightening in the final year of the forecast, £28.0 billion (45 per cent) comes from reductions in the planned path of departmental spending.a Over the course of the next five years:

- 2021 Spending Review (SR21) plans (covering the period to 2024-25) are little changed by policy in the Autumn Statement for capital spending (CDEL), whereas current spending (RDEL) is higher (by £2.5 billion in 2024-25). This reflects increased funding for the NHS, social care and schools, the cost of which is largely offset by reducing aid spending from 0.7 to 0.5 per cent of national income. We have also revised down assumed underspending against the departmental limits set in cash terms by the Treasury last year – by £2.5 billion in 2022-23 and £0.7 billion in 2023-24 – due to higher inflation and wage rises. Even before any other changes, higher-than-expected inflation means that real growth in total DEL would have been 2.2 per cent a year, rather than the 3.1 per cent assumed when plans were set in October 2021.

- The capital spending envelope beyond 2024-25 is held flat in cash terms (thereby falling by 1.2 per cent a year in real terms), a material reduction from the previous assumption of growth in line with nominal GDP (a 2.5 per cent a year real-terms increase). This reduces cash spending by amounts rising to £14.1 billion by 2027-28 and lowers CDEL

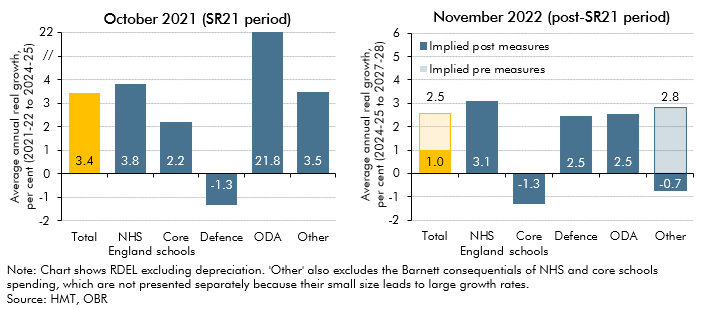

spending by 0.4 per cent of GDP to 3.3 per cent of GDP in 2027-28, reversing around half the March 2020 Budget increases. - The current spending envelope beyond 2024-25 rises by 1 per cent a year in real terms, lower than the previous assumption of growth in line with nominal GDP (again, 2.5 per cent a year in real terms). This reduces cash spending by amounts rising to £22.2 billion in 2027-28. Real growth is below the 3.4 per cent a year rise initially planned for the SR21 period (Chart D), but above the falls of 2.3 per cent a year and 0.8 per cent a year respectively that were initially planned in the 2010 and 2015 Spending Reviews.

As usual, the forecast beyond the current Spending Review period is based on overall current and capital spending totals set by the Treasury rather than detailed plans. But we can explore the implications of these cuts in the growth of public services spending by considering what existing input targets and past commitments in some areas imply for growth in spending in other areas not covered by such targets – often termed ‘unprotected’ spending. Specifically, we have looked at the proposed post-SR21 RDEL path based on the following assumptions:

- Spending on the NHS in England grows in real terms by 3.1 per cent a year, which would maintain the spending growth rate originally planned in the 2021 Spending Review for the period from 2019-20 to 2024-25 (excluding temporary Covid-related spending). This is slightly less than the 3.4 per cent a year real-terms growth that resulted from Prime Minister May’s June 2018 NHS settlement.

- Core schools spending is held flat per-pupil in real terms, reflecting then Chancellor Sunak’s statement that SR21 restored per pupil spending to 2010 levels in real terms.b

- Defence spending is held flat as a share of GDP, consistent with the Government’s commitment to keep such spending above the NATO minimum of 2 per cent of GDP. (Using the pledges made by the previous two Prime Ministers – of reaching 2½ or 3 per cent of GDP, respectively – would increase the squeeze on unprotected spending.)

- Spending on Official Development Assistance (ODA) is maintained at 0.5 per cent of gross national income (GNI) throughout the forecast, whereas in our March forecast it was expected to rise to 0.7 per cent of GNI from 2024-25 onwards.c

- The consequences of our NHS and schools spending assumptions for devolved administrations are captured using the Barnett formula.

These assumptions leave other ‘unprotected’ spending falling by 0.7 per cent a year in real terms from 2025-26 onwards. This would be considerably tighter than the 3.5 per cent a year real growth originally planned for these departments over the SR21 period (Chart D), but much smaller than the real-terms cuts planned in the 2010 and 2015 Spending Reviews (average

annual real-terms falls of 5.0 per cent and 3.3 per cent, respectively).

Chart D: Planned SR21 and implied post-SR21 breakdown of RDEL spending

While the reduction in day-to-day spending is less than in previous periods of consolidation, it still presents challenges and risks to our forecast. Various performance indicators for public services continue to show signs of strain, not least the record 7.1 million waiting list for NHS elective treatments in England, which has risen by 2.8 million since the pandemic.d And recent history shows that governments tend to top up spending envelopes as the difficult moment of allocating them out in Spending Reviews approaches. Between December 2014 and SR day in November 2015, cash RDEL totals across the 2015 Spending Review period were raised by £37 billion (13.0 per cent) a year on average. The same happened between March 2021 and SR day in October 2021, when cash RDEL totals were raised by £32 billion (7.7 per cent) a year on average over the 2021 Spending Review period.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2022