The unusual nature and size of the prevailing economic shock, and the Government’s fiscal response, raised the question of whether our usual fiscal multipliers were appropriate at the time. This box set out competing arguments for the multipliers being larger or smaller than those we usually employ and concluded that we would leave them largely unchanged.

We normally evaluate the output consequences of fiscal measures by applying ‘fiscal multipliers’ based on the historical impact of additional public spending or tax cuts on the economy. These multipliers capture the indirect effects of the fiscal measures on activity over and above their immediate effect on demand and through raising private incomes and spending. However, they also take account of the consequent upward pressure this puts on wages and prices and the monetary policy response by the Bank of England necessary to keep inflation at target, which explains why they taper to zero over the five year forecast horizon.a The unusual nature and size of the current economic shock and of the Government’s fiscal response raise the question of whether such multipliers should be different in the present circumstances.

There are several reasons why multipliers might be higher than usual at the moment:

- The proximity of policy interest rates to their lower bound means monetary policy may be less able to respond to changes in the margin of spare capacity and inflationary pressure.b If that were the case, then ‘financial crowding out’ would be weaker. Policymakers at the Bank of England believe, however, that they still have considerable monetary firepower available in the form of further asset purchases (quantitative easing) and targeted loan support (credit easing) and which could be scaled back if inflationary pressures were to build.c

- There is less room to crowd out private sector investment when private capital spending has already been cut sharply in response to the pandemic and Brexit. In our central forecast, business investment in the second half of the 2020-21 fiscal year is down almost 25 per cent on a year earlier.

- There may be less upward pressure on inflation from extra spending when there is a large margin of spare capacity in the economy. While we do judge there to be a modest output gap of around 1 per cent in the second half of 2020-21, the simultaneous fall in supply and demand as a result of the virus and related public health measures means that it is very much less than the reduction in activity. It is also small compared to the output gap that followed the 2008 financial crisis.

There are also several reasons why multipliers might be lower than usual:

- Public health restrictions and voluntary social distancing by households mean that spending in sectors such as hospitality, transport and tourism may be quite insensitive to fiscal expansion, with some consumers (especially those with higher incomes) saving more instead. That may explain why the household saving rate leapt to 28 per cent in the second quarter of this year, though the extra savings may subsequently sustain a stronger rebound in spending.

- In addition to this ‘forced’ saving, households’ concerns about future employment and earnings prospects could prompt an increase in precautionary saving. This would also reduce households’ propensity to spend out of extra income received via any fiscal stimulus.

- Some of the additional government spending during the pandemic has an unusually high import content. The vast majority of government spending on personal protective equipment (PPE) and coronavirus testing kits to date has been on imports.d This increased foreign ‘leakage’ reduces the domestic fiscal impulse provided by government spending and thus its effect on GDP in the UK.

Given the arguments on both sides, there is considerable uncertainty about the appropriate multipliers to apply at the current juncture. The US Congressional Budget Office recently published an analysis of the likely effects of pandemic-related measures there on output, which also posited several factors that might leave multipliers higher or lower at the moment.e

In this EFO, we have largely employed the same set of multipliers as in previous forecasts but have diverged from these in three respects. First, we have reduced the impact multiplier on departmental spending by a quarter to reflect the greater import-intensity of that spending relative to existing departmental spending. Second, we have assumed that spending on the extended job retention and self-employment support schemes has one quarter of the impact on demand as typical non-departmental spending, to reflect the greater likelihood of forced or precautionary saving by recipients and that some could have borrowed in the absence of these schemes to smooth consumption. Third, in the absence of a standard approach to factoring in the impact of loan guarantee schemes, we have assumed that extending the schemes has a modest short-term effect on demand.

Extending the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) to March also means that the output consequences of the second wave and the public health restrictions to contain it are mainly felt in lower average hours worked rather than in higher unemployment, delaying and lowering the rise in unemployment.

In addition to the short-term economic impact of the fiscal measures, there is the important question of their impact in the longer term.

- By helping to contain the spread of the virus, some of the health-related spending, especially on testing and tracing, and on vaccine development and deployment, facilitates the application of less stringent public health restrictions and an earlier return to normal life. It thus helps to push the trajectory of output towards our more optimistic scenario. It is very difficult to know how to calibrate this effect, but the experience of South Korea, where test, trace and isolate has been effective in keeping the economy open, demonstrates just how significant it may be.

- A key objective of the CJRS and the loan guarantee schemes is to avoid the long-term scarring of potential output that could arise if viable jobs and businesses are lost. Again, it is extremely difficult to quantify this effect of the measures because there is so little previous experience to draw on, though it too may be substantial.

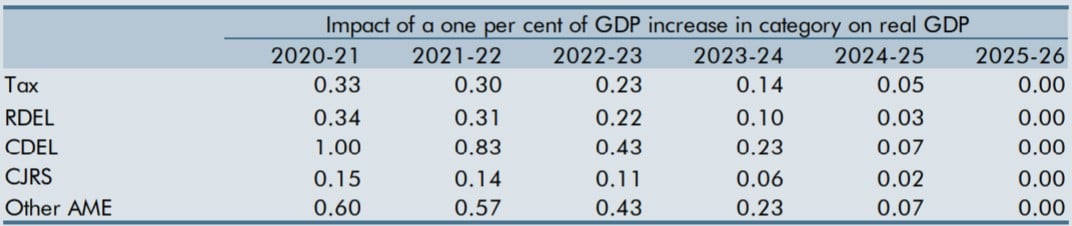

Table A summarises the fiscal multipliers used in this EFO. As in recent EFOs we assume that the multipliers taper from the point of announcement rather than from the point of implementation.

Table A: Fiscal multipliers

With new measures factored into this forecast totalling around £100 billion in 2020-21 and £40 billion in 2021-22, real GDP would have likely taken a materially weaker near-term path in their absence. A mechanical application of the multipliers in Table A implies that the level of GDP would have been almost 3 per cent lower, absent the latest measures, at the peak of their impact at the start of 2021. The combined effect of this and the extension of the CJRS, means that unemployment would have peaked two quarters earlier and at a higher level without the latest measures. We estimate that unemployment would have been about 300,000 higher in the second quarter of 2021 in the absence of these measures.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2020