Box sets » Labour market » Employment and unemployment

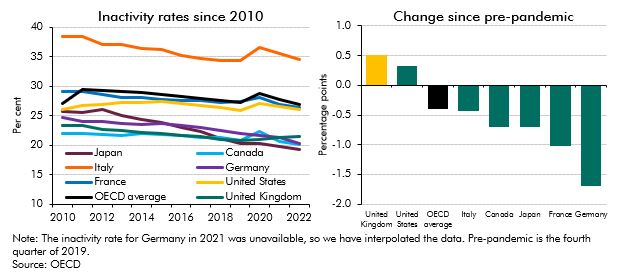

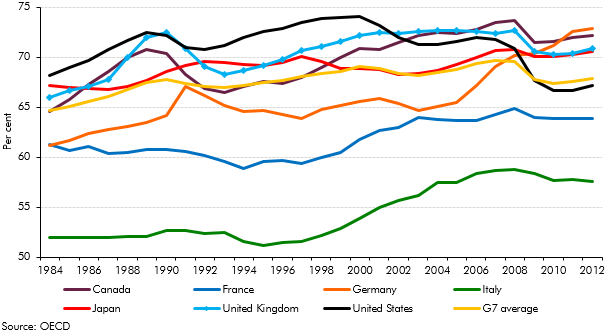

Inactivity fell across the G7 countries in the years prior to the onset of the pandemic and the UK consistently had one of the lowest inactivity rates. Since then inactivity has risen in the UK and US, but fallen across the rest of the G7 countries. This box detailed these changes and looked at ill-health as a driver of inactivity across the G7.

The referral to elective treatment waiting list in England has risen steadily since the onset of the pandemic, to 7.4 million treatments in April 2023. This box used waiting list and LFS data to estimate the effect on employment and inactivity of halving the waiting list by 2027-28.

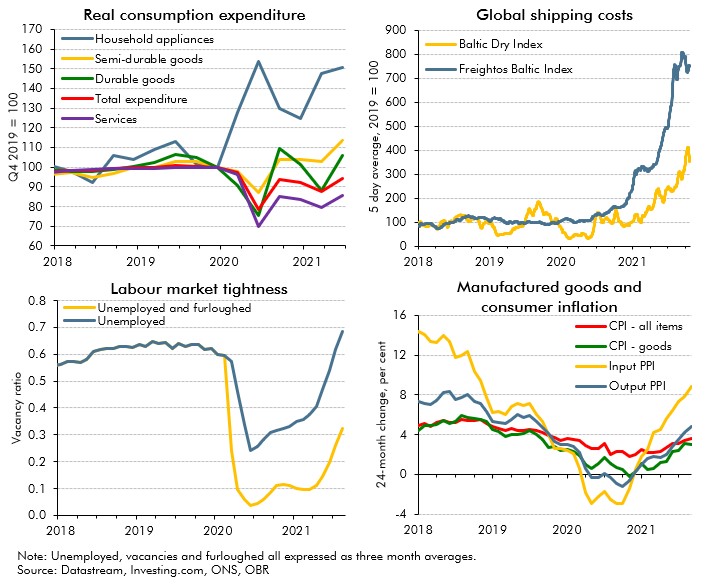

In October 2021 commentators became increasingly concerned that the inability of supply to keep up with demand in specific areas of the economy would hold back the recovery. In this box we examined these 'supply bottlenecks' in energy, product and labour markets, discussing their consequences for wage and price inflation.

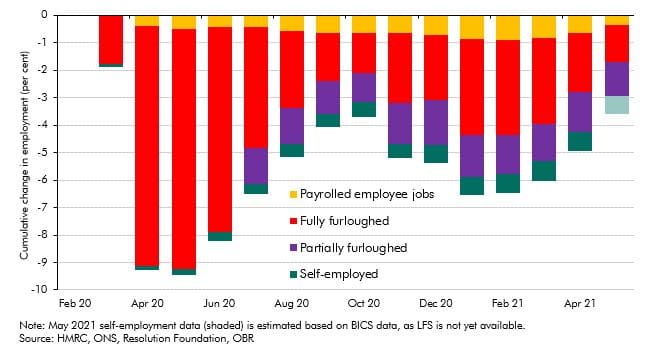

The Government announced in March 2021 that the coronavirus job retention scheme (CJRS) would be phased out completely by the end of September 2021. In this box, we looked at the latest evidence on the number of people on the scheme and their concentration in certain industries, as well as the latest data on vacancy rates. We also discussed how these data related to our labour market assumptions from March 2021.

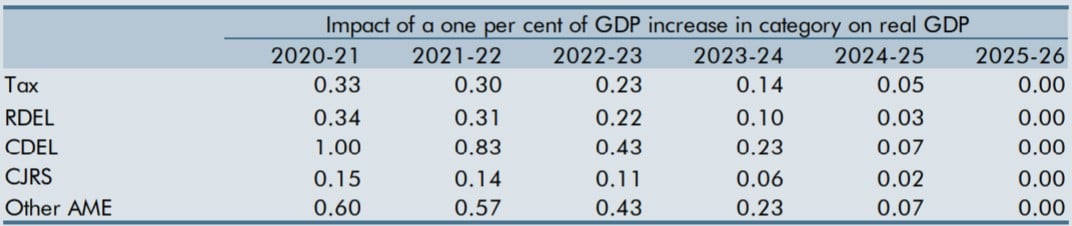

The unusual nature and size of the prevailing economic shock, and the Government’s fiscal response, raised the question of whether our usual fiscal multipliers were appropriate at the time. This box set out competing arguments for the multipliers being larger or smaller than those we usually employ and concluded that we would leave them largely unchanged.

In March 2020, the Government introduced a new target for the National Living Wage (NLW) to reach two-thirds of median earnings (of the relevant population) by 2024, providing economic conditions allow. In this box we considered the effect of this policy change on the outlook for the economy and the public finances.

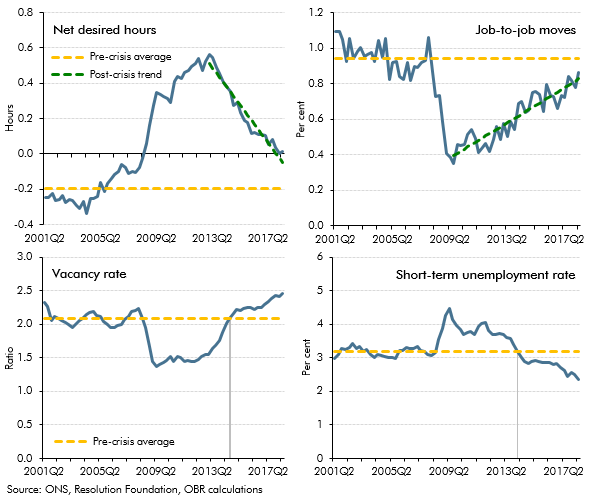

In the 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook we discussed how the unemployment rate – which had fallen to its lowest level since 1975 – may not necessarily give a complete picture of the extent of labour market slack. This box therefore looked at some other measures, some of which suggested there could be more spare capacity than was captured by the unemployment rate at that time and some of which could be used to argue that there was less.

Alongside the October 2018 Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) the Government expressed its aspiration to end low pay, noting the definition used by the OECD, which corresponds to two-thirds of median earnings. This policy was not firm enough for us to incorporate into our central forecast. Nevertheless, in this box we drew on previous analysis from our July 2015 EFO – when the National Living Wage was first introduced – to illustrate the potential effect on the economy and public finances.

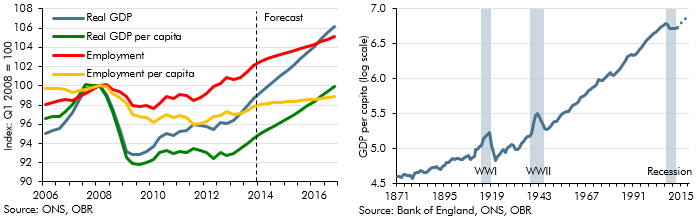

As part of our economic forecast, we produce forecasts for total employment and GDP per capita based on ONS population projections. Relative to our June 2010 forecast, employment in 2015 was 1 million higher than expected and GDP per capita over the period increased by 4.5 per cent lower. This box from our July 2015 Economic and fiscal outlook examined the reasons for these forecast errors.

Between 2012 and 2014, growth in the UK picked up, outpacing all other members of the G7. This box provided wider context for this strength in UK growth, comparing GDP, employment and productivity growth across G7 countries since 2008.

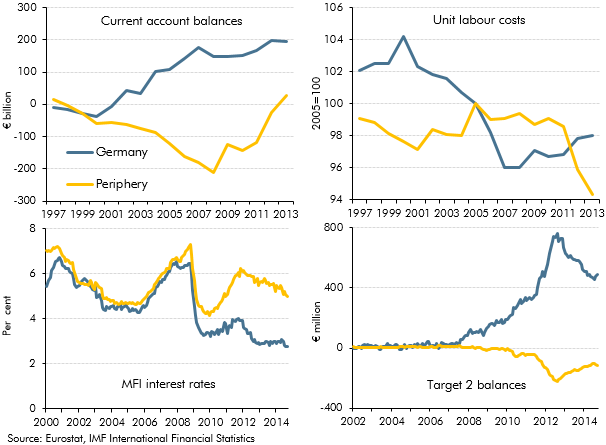

In the December 2014 Economic and fiscal outlook, we identified the adjustment in the euro area as a risk to our forecast. This box highlighted some of the key indicators that commentators were using to measure the progress of that rebalancing.

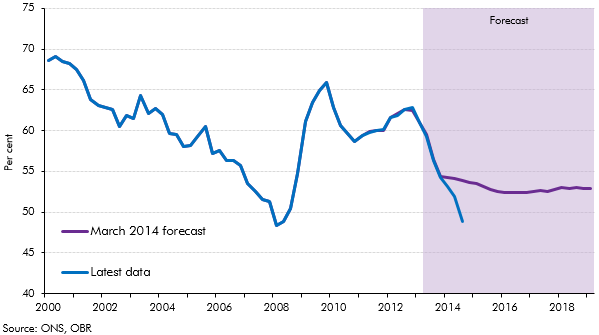

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 8 considered spending on unemployed people. This box compared outturn data on unemployment and claimants of unemployment benefits to the levels implied by our March 2014 forecast. As the economy performed better than anticipated in our March 2014 forecast, the ratio of claimants of unemployed benefits to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) measure of unemployment deviated from our projections. This was largely due to a drop in the rate of inflows into unemployment benefits and a rise in the rate of outflows from unemployment benefits, though an increase in the number of people looking for jobs but not claiming unemployment benefits may have increased LFS unemployment and so been a contributing factor.

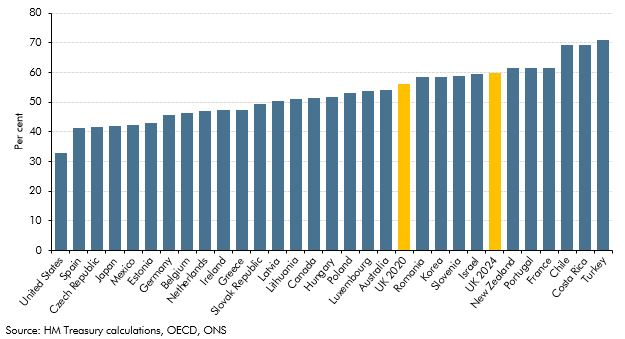

Earlier in the year, the Chancellor expressed an ambition “to have more people working than any of the other countries in the G7 group". This box compared countries employment rates and demonstrated the scope for labour market outcomes to differ substantially.

In the February 2014 Inflation Report the Bank of England published more information about its assessment of spare capacity. This box compared that assessment with our own output gap estimate at the time, highlighting some conceptual differences between the two.

This box showed how growth in some of the key economy variables between 2010 and 2013 was lower when measured on a per capita basis. We also discussed our forecast for productivity growth at that time, given its importance in determining GDP per capita growth in the medium term.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2014 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to inflation and business investment.

On 7 August 2013, the Bank of England announced that it would not consider raising Bank Rate, then at 0.5 per cent, until the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.0 per cent. However, the Bank also detailed certain conditions, which if breached, would make it consider tightening monetary policy sooner. This box, from our December 2013 Economic and fiscal outlook, examined where our forecast stood in relation to these conditions.

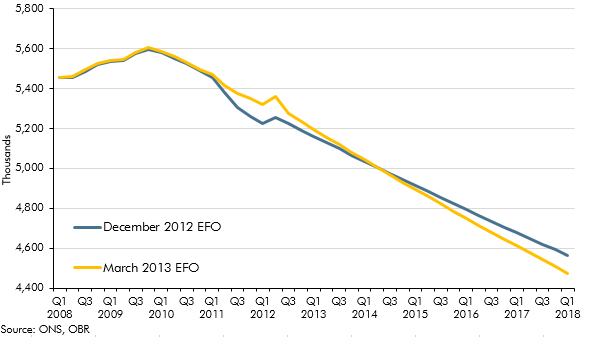

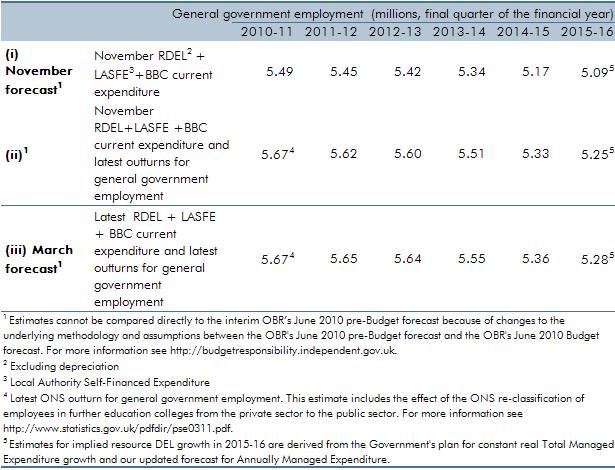

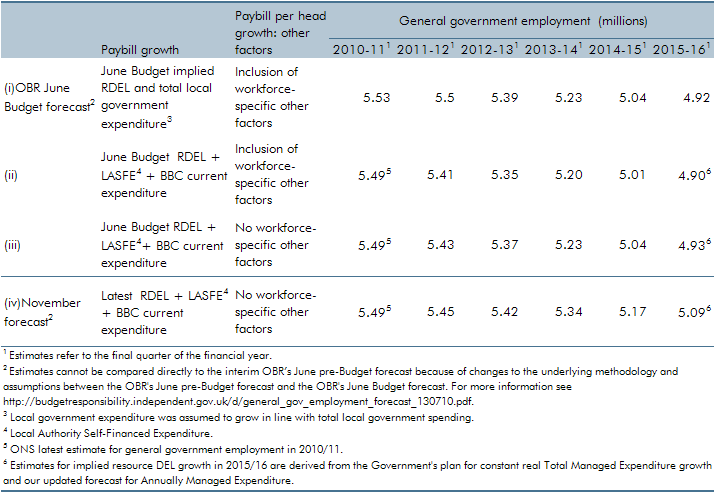

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. In this box we compared our GGE forecast against the outturn data since the start of the 2010 Spending Review period. This allowed some assessment of how public sector employers were progressing with their intended workforce reduction and how much adjustment would still be required.

In October 2011, we published our first Forecast evaluation report (FER). This box summarised the key findings, including a discussion of weaker than expected GDP growth and why, despite this, public sector borrowing has fallen broadly as we expected it would.

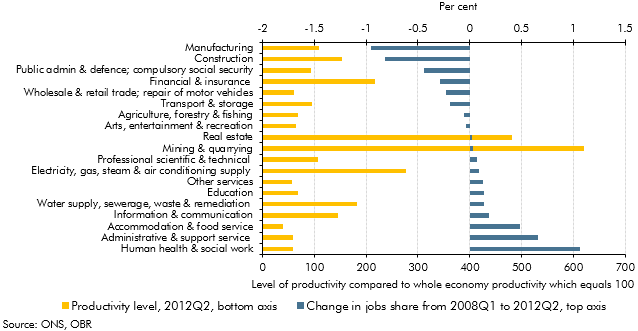

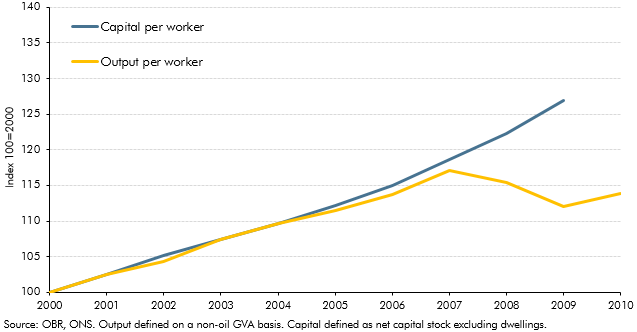

Productivity growth since the late-2000s recession has been relatively weak. This box set out some proposed explanations for that weakness, including measurement issues, lower investment, compositional effects, labour market factors and impaired financial markets. Most commentators believed that some combination of these factors was likely to be responsible. The relative importance of these factors also has implications for the extent to which the shortfall was believed to be demand or supply-related.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. In this box we compared our GGE forecast against the outturn data since the start of the 2010 Spending Review period. This allowed some assessment of how public sector employers were progressing with their intended workforce reduction and how much adjustment would still be required.

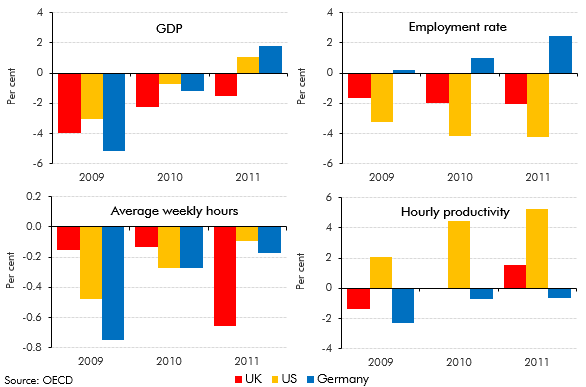

The UK, the US and Germany all saw broadly similar falls in GDP over 2009, but their labour markets responded differently. This box discussed these differences and compared the behaviour of employment, hours and productivity over this period.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. In this box we compared our GGE forecast against the outturn data since the start of the 2010 Spending Review period. This allowed some assessment of how public sector employers were progressing with their intended workforce reduction and how much adjustment would still be required.

Potential output growth had been relatively weak in the period following the late-2000s recession. This box discussed some possible reasons, noting that indicators available at the time did not indicate a structural deterioration in the labour market.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2011 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to our forecasts of inflation and property transactions.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. In this box we compared our GGE forecast against the outturn data since the start of the 2010 Spending Review period. This allowed some assessment of how public sector employers were progressing with their intended workforce reduction and how much adjustment would still be required.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. Ahead of our March 2011 forecast, ONS estimates of general government employment were revised up, largely reflecting the reclassification of employees in further education colleges. In this box we set out the extent to which changes to our general government employment forecast were a result of our revised projections for paybill growth as opposed to data revisions.

In our central forecast, interest rates are assumed to evolve in line with financial market expectations. For alternative economic scenarios which involve different paths for the output gap and inflation, it is useful to specify rules for the way monetary policy is set and for how output and employment will respond. In this box, we set out the rules that governed those relationships in the scenarios we analysed in the March 2011 Economic and fiscal outlook: a persistent inflation scenario and a weak euro scenario.

Following the June 2010 Budget, the Government set out further details of the planned reductions in government expenditure in its 2010 Spending Review, including additional measures to reduce welfare spending. This box discussed the possible ways in which these measures could affect the economy's trend growth rate.

Data available at the time of our November 2010 Economic and fiscal outlook suggested that general government employment fell by 550,000 between 1992 and 1998. But some of this fall reflected the reclassification of further education colleges and sixth-form school employees from the public to the private sector in 1993. This box outlined a simple methodology which suggested that general government employment would have fallen by just over 400,000 over that period in the absence of this reclassification.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. Ahead of our November 2010 forecast, those plans were updated as part of the 2010 Spending Review. We also made a number of refinements to our forecasting approach. In this box we described revisions to our general government employment forecast and explain the extent to which these changes were the result of methodological changes as opposed to revised spending plans.