In Autumn Budget 2017, the Government announced the introduction of a permanent stamp duty land tax (SDLT) relief for first-time buyers. This box considered the effects of a previous temporary relief for first-time buyers and how the new permanent relief was expected to affect tax receipts and house prices.

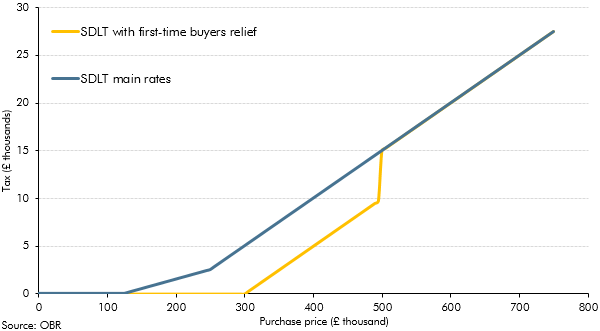

The Government will introduce a new permanent relief for certain first-time buyers (FTBs) that will reduce stamp duty land tax (SDLT) to zero on properties up to £300,000. A rate of 5 per cent will be charged on the value between £300,001 and £500,000. But FTBs buying a property for £500,001 or more will not benefit from the relief at all, so a purchase at that price would be liable to £5,000 more in SDLT than one at £500,000. Eligibility criteria match those of the post-crisis ‘stamp duty holiday’, although then the relief stopped at £250,000. HMRC published an evaluation part way through that holiday. It concluded that the majority of the value of relief had fed through to higher house prices and that it “has not had a significant impact in terms of improving the affordability of residential property for FTBs. It is estimated that most of the buyers who benefitted from the relief would have purchased property in its absence anyway (i.e. are deadweight).”a Confirmation that the relief would end was announced alongside the evaluation.

The costing of this measure uses recent mortgage data on FTBs. The proportion of FTBs in all new mortgage lending recently jumped from around 40 to over 45 per cent of all mortgages. This coincided with the introduction of the SDLT surcharge on additional property purchases in April 2016. As with the post-crisis holiday, we have assumed that the consequence of introducing the relief will be to increase house prices – in this case by around 0.3 per cent (see Box 3.1). The effect on prices of a permanent relief should be greater than a temporary one of equivalent value because it will benefit future FTBs of a property, not just those who buy during the window in which the temporary relief is available. The effect of this reduction in future SDLT costs would be expected to feed through into house prices – to be ‘capitalised’ – relatively quickly. Since the relief frees up FTBs’ savings to put towards higher deposits, these higher prices can be paid.

We assume that a temporary relief would feed one-for-one into house prices, but a permanent one will have twice that effect. On this basis, post-SDLT prices paid by FTBs would actually be higher with the relief than without it. Thus the main gainers from the policy are people who already own property, not the FTBs themselves. For some potential FTBs with smaller deposits, who are constrained by loan-to-value lending criteria, the relief will enable them to borrow a multiple of their SDLT saving, allowing them to buy properties that they otherwise could not afford – but more expensively.

There are two other behavioural effects on the public finances that are worth noting. First, the relief will distort the housing market at prices around £500,000. Chart D shows the jump in the effective tax rate at that price. This will reduce receipts as FTB transactions bunch below the threshold. Second, it is likely that some FTB purchases will displace purchasers who would have paid more SDLT on the equivalent purchase.

Chart D: SDLT liability at different house prices: with and without FTB relief

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2017