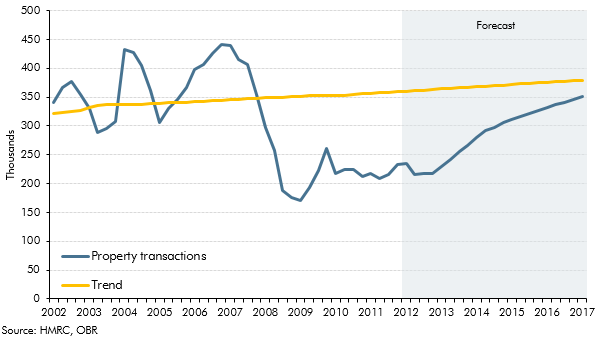

We forecast two housing variables that are important determinants of parts of our fiscal forecasts: house prices, as measured by the ONS house price index, and the number of transactions that take place, as reported by HMRC. Most importantly, the value of property transactions (i.e. the number times the average price) is the main driver of stamp duty receipts. Some property transactions will also be subject to capital gains tax or inheritance tax. These housing variables also feed into our forecasts for other elements of the economy forecast (such as RPI inflation, mortgage debt and residential investment).

We also produce a forecast of the stock of dwellings across the UK – the ‘housing stock’. This is used to inform our forecast for residential investment and is an input into our forecasts of house prices and property transactions. This is also used to ensure that our fiscal forecast for council tax – which is levied on the stock of dwellings – is consistent with the judgements in our economy forecast.