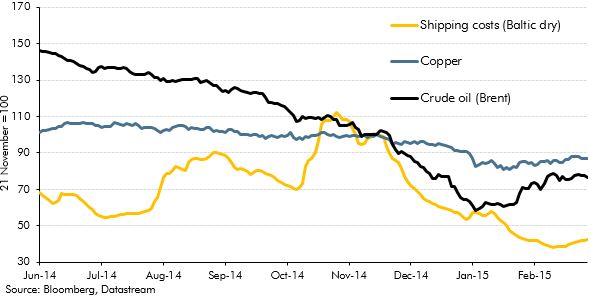

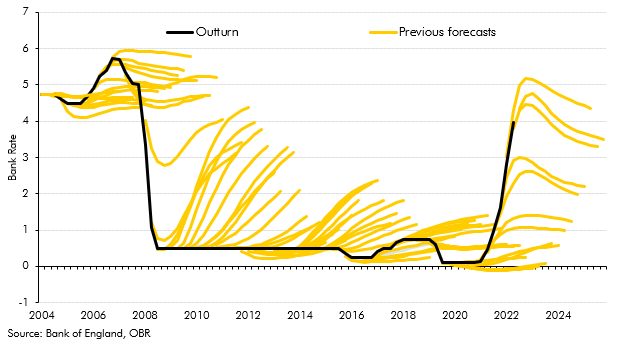

We forecast several variables by using the expected values that are implicit in the prices of financial market instruments. Since these reflect the collective views of the large number of investors in each market, it seems unlikely that our own forecasts could systematically outperform these values. We use this approach for oil prices, natural gas prices and interest rates. We also forecast equity prices by using the latest market values and projecting them to grow in line with our forecast for nominal GDP. The exchange rate is assumed to follow a ‘random walk’, meaning it is held flat over the forecast period. The rest of the economy forecast is then in effect conditioned on these implied financial market expectations of the likely future paths of these variables.

Financial market indicators can be volatile, responding to news and events from day-to-day. We therefore normally base our forecasts on the market-implied expectations over a 10-working day window – a period that aims to be short enough to capture the latest market view, but long enough to be less susceptible to day-to-day volatility. For our March 2024 forecast, this was the 10 working days up to and including 23rd January. Usually, at the start of the forecast process, we agree a forecast timetable with the Treasury that includes the dates at which we will take financial market expectations. We would normally set the 10-working day window for our final economy forecast to be as near as possible to the point where we close down the forecast to everything but the effects of new policies. But on occasion, we have adopted other approaches – for instance, our March 2023 economy and fiscal forecasts were based on an average of the five days following the publication of the Bank of England’s February 2023 Monetary Policy Report so that the expectations fully incorporated the information contained in the report.