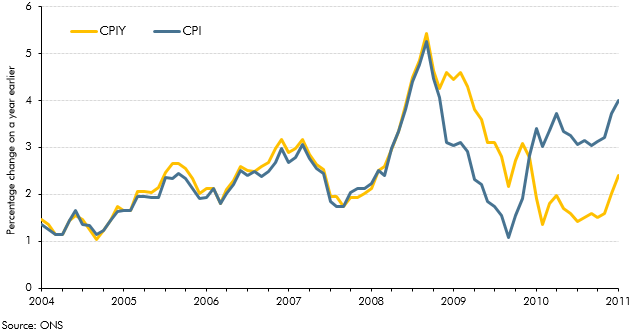

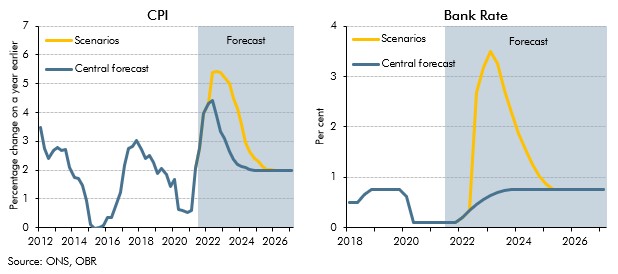

We produce forecasts for the Consumer Prices Index (CPI inflation) and the Retail Prices Index (RPI inflation). The Government uses these measures in various ways. It has set the Bank of England a 2 per cent CPI inflation target. In terms of tax and spending, if the Government has not set another specific policy, CPI inflation is used in the income tax system to set the path for allowances and thresholds each year and in the social security system to uprate statutory payments for most working-age benefits. RPI inflation is used to set the path for most excise duty rates. RPI inflation also determines the amount of interest paid on index-linked government debt and interest charged on student loans.

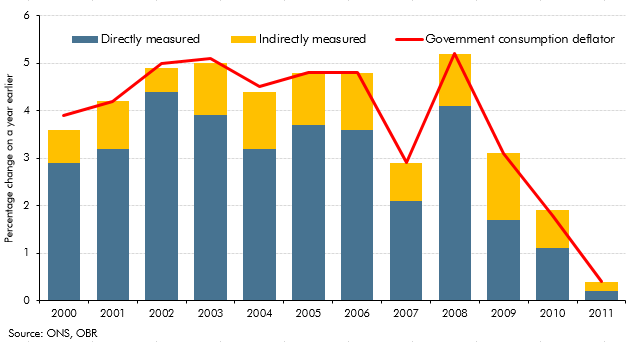

We also forecast inflation at the whole economy level. This is required to produce a forecast for the cash size of the economy, which is the most important driver of our tax forecasts. The GDP deflator includes not only inflation related to consumer spending, but also to investment, trade and the activities of government.

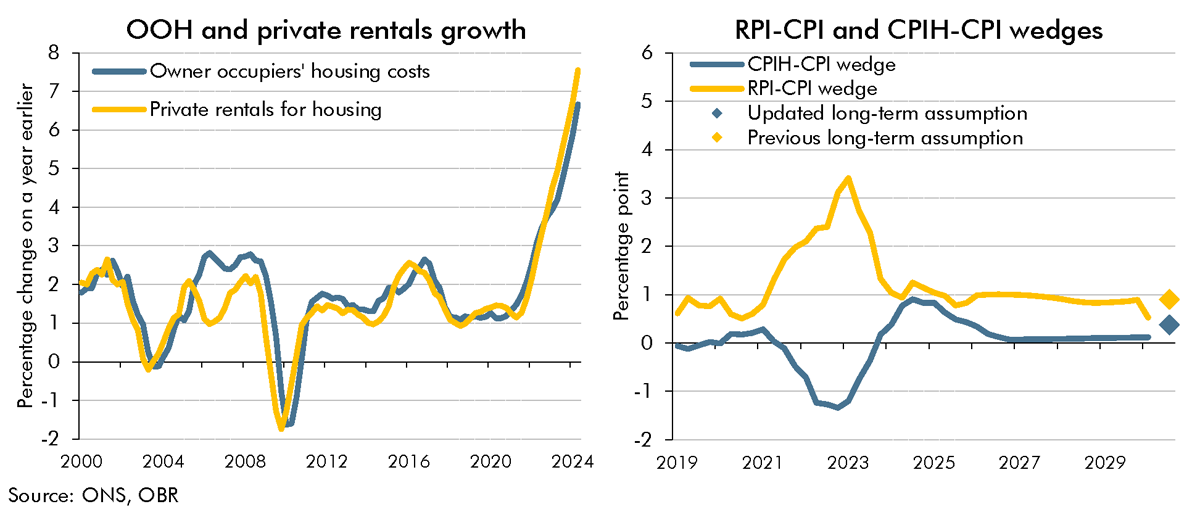

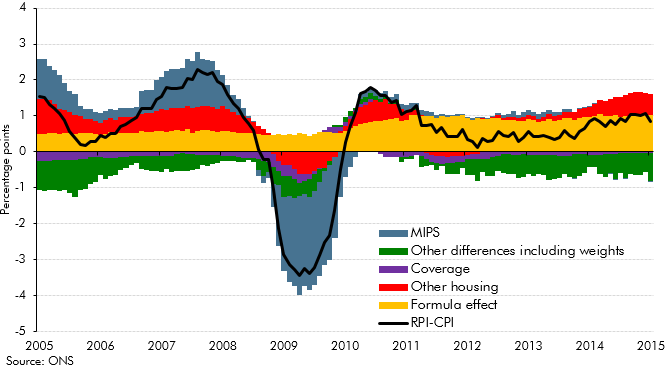

The forecast process starts by thinking about CPI inflation prospects in the short and medium term, with different sets of models used at each of the two time horizons and their outputs combined. That provides the base for our RPI inflation forecast (which is produced by making various adjustments to get from CPI to RPI) and drives the consumption deflator forecast which is the largest component of the GDP deflator. The adjustments needed to get from CPI to RPI also allow us to forecast RPIX inflation.