In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2022 Economic and fiscal outlook, we adjusted our forecast to account for the loosening of fiscal policy, including a temporary capital allowance. And, we considered the effects of policy to boost employment on our potential output forecast.

This box is based on OBR data from March 2023 .

Our economic forecasts account for the economic impact of the latest announced government policies. This includes estimates of the direct fiscal costs or savings from all policy measures and their near-term demand-side impacts on the economy. To estimate the effect of discretionary fiscal policy changes on aggregate demand, we use multipliers drawn from the empirical literature. These capture wider effects of fiscal policy measures on output over and above their direct effects on demand, through changes to private incomes and spending. We review these estimates periodically.a The impact of policies on the supply side of the economy is also accounted for if credible evidence suggests that measures will have a material, additional, and durable impact on potential output.b

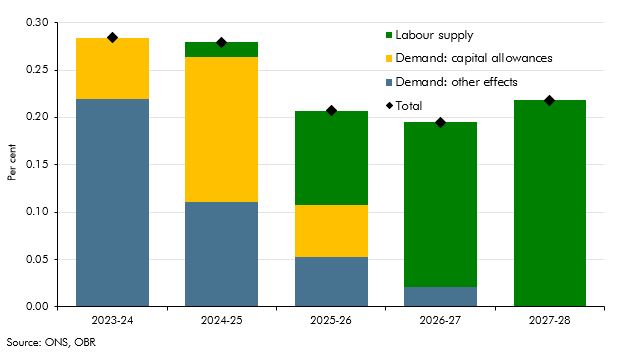

Policies announced in this Budget add around £20 billion a year to public sector net borrowing between 2023-24 and 2025-26, declining to around £10 billion by 2027-28. Of this package, the near-term fiscal loosening boosts aggregate demand relative to supply by 0.3 per cent at the peak of its impact in 2023-24 and 2024-25, narrowing the output gap by the same amount. As usual, we assume the demand impact of these policies tapers to zero over the forecast period, as the Bank of England acts to offset any inflationary pressure by tightening monetary policy to bring aggregate demand in line with potential output.

In 2024-25 in particular, this 0.3 per cent figure largely reflects the impact of the temporary increase in the generosity of capital allowances for businesses, which lets firms reduce their taxable profits by 100 per cent of the cost of their investments in plant and machinery for three years from April 2023. This incentive to accelerate investment plans boosts our business investment forecast by amounts peaking at almost 3½ per cent in 2024-25 and 2025-26. But the policy’s temporary nature leaves the optimal capital stock unchanged in the long run, so in the final year of the forecast business investment is 4 per cent lower than it would otherwise be. We assume that around half of the additional investment is imported, so the initial impact on GDP is smaller than the impact on our business investment forecast would imply.

In addition to these impacts on demand, the Government has announced a £7 billion package of support to target labour supply. We judge that five policies in the Spring Budget will have a material and positive impact on supply, specifically labour supply, and have explicitly incorporated their effects into our forecast for potential output. Of these:

- We expect the new 30 hours a week of free childcare for working parents of nine-month-to two-year-olds to gradually increase labour market participation of parents with young children. By 2027-28, we expect around 60,000 to enter employment and work an average of around 16 hours a week (in line with the average for part-time workers). An equivalent effect on total hours comes from the 1½ million mothers of very young children already in work increasing the hours they work by a much smaller amount. This policy has by far the largest impact on potential output in this Budget.c

- We have increased employment by around 15,000 at the forecast horizon to account for the impact of changes to childcare support within universal credit, in particular reimbursing parents for the first month’s fees upfront.d

- Increasing conditionality on parents and carers claiming universal credit increases labour supply marginally at the forecast horizon by encouraging people to increase their work search intensity, raising employment by up to 10,000.

- Changes to the lifetime allowance and annual allowance on pension contributions increase employment by around 15,000 by removing some financial disincentives to continuing in employment for those with large pension pots.e

- A new disability employment programme will collect referrals from the health-related benefits system and other settings to support inactive disabled people into sustained work. We assume this will increase employment by 10,000, based in part on evaluations of similar programmes.f

Relative to our pre-measures forecast, our central estimate is that these policies, taken together, increase employment by 0.3 per cent (110,000) by 2027-28. But part of the employment impact on potential output is offset by lower-than-average hours and earnings among many of the new joiners, so the overall impact on GDP is around 0.2 per cent in 2027-28. This is the largest upward revision we have made to potential output within our five-year forecast as a result of fiscal policy decisions taken by a Government in any of our forecasts since 2010.g

Chart B: Impact of policy measures on real GDP

The bringing forward of investment to benefit from a temporary capital allowance policy will not alter the path of the capital stock or potential output in the long run (i.e., beyond our forecast horizon), but it does temporarily place the capital stock on a higher path. We estimate that it will be higher by 0.2 per cent in 2027-28. This is roughly in line with the increase in total hours from policy interventions, therefore there is no change to the capital intensity of the economy, leaving the level of potential productivity per hour unchanged. The Chancellor has indicated his intention to make the measure permanent when economic and fiscal conditions allow – we discuss the implications this would have for our forecast in paragraph 2.34.

Our central estimate of the increase in labour supply as a result of the policies announced in this Budget is very uncertain, and a plausible range could be as high as 240,000 or as low as 55,000 based on alternative plausible assumptions. The higher estimate might reflect: the increase in mothers’ participation matching historical estimates of changes in participation rates when children go to school; more individuals responding to the changes to the lifetime and annual pension allowances than expected; caseloads for the new disability employment programme being higher than we expect; and changes to universal credit conditionality and childcare payments bringing more people than expected into work. It is also plausible that a lower figure could occur, for instance if parents’ labour market decisions are less responsive to childcare provision or if changes to the pension allowances do not incentivise workers to stay longer in the labour force.

It will be important to monitor the implementation of these policies to ensure that additional resources are being provided to deliver the proposed interventions, rather than them being reprioritised from other programmes, and that programmes are being executed according to the timetables assumed in our forecast. And our ongoing assessment of their economic impact will also be informed by a regular programme of rigorous evaluation of the various interventions which we will draw on to refine our estimates of their supply-side impact over time.

Other policies announced in this Budget directly affect inflation. Taken together, the freezing of fuel duty, changes to alcohol duty and the extension of the EPG lower CPI inflation by 0.7 percentage points in 2023-24. The effects of subsequent increases to fuel and alcohol duties and the EPG measure then add 0.4 percentage points to CPI inflation in 2024-25.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2023