Where the Government uses off-balance sheet financing to deliver public services this results in a 'fiscal illusion', where the recorded measures of debt and deficit do not reflect economic reality. In this box we looked at the case of housing associations (HAs). These came onto the balance sheet after the Government was given significant controls over them. The Government then legislated just enough to move HAs off-balance sheet. Neither movement made any fundamental change to fiscal sustainability.

This box is based on ONS data from June 2019 .

Successive reclassifications of housing associations into and then back out of the public sector have generated large balance sheet transfers and affected our recent forecasts. The move back into the private sector returns them to the status of a ‘fiscal illusion’, having briefly featured in the full public finances data. The nature of the illusion stems from their use to deliver a public policy objective and the related likelihood that the Government ultimately stands behind them.

The 2008 Housing and Regeneration Act gave the Government significant controls over housing associations in England, but these powers were not used to a fiscally material extent until Summer Budget 2015, when the Government announced that it would force housing associations to cut social sector rents by 1 per cent a year for four years, thereby reducing the housing benefit bill on their properties. In our accompanying Economic and fiscal outlook we noted that this might prompt the ONS to reconsider their classification in the private sector. In October 2015, the ONS reclassified English housing associations into the public sector, with effect from 2008 when the relevant legislation had been enacted. It then reviewed the treatment of associations in the rest of the UK and took the same decision for them in September 2016.a We noted at the time that these changes raised PSND, but did not materially affect fiscal sustainability.

Later, the Government took legislative steps to reduce its control over housing associations. It was unusually candid in admitting that those steps were precisely calibrated to relinquish just enough control to allow the ONS to reverse its decision, but no more.b On the back of these regulatory changes, the ONS reclassified English housing associations back to the private sector with effect from November 2017.c Scottish and Welsh associations followed a year later, reflecting slower passage of relevant regulations through the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Assembly.

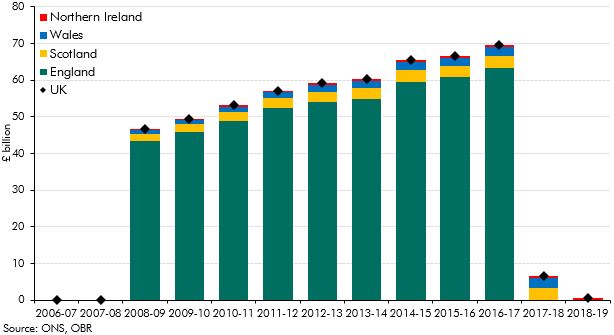

Chart A: Housing associations’ contribution to PSND

Our 2017 Fiscal risks report highlighted the potential reduction in PSND that would follow the Government’s desired reclassification, were it to happen. But it also noted that the implications of housing associations for fiscal sustainability would be little changed either way since their role as providers of social housing would not change – and neither would the likelihood that the Government would stand behind them were they to face financial difficulties in future.

This episode highlights the degree to which statistical boundaries can drive regulatory policy decisions. This is probably not unusual, although this instance was unusual for the Government’s candour about its motivation in designing the regulatory changes that were enacted.