In February 2020, the Government announced its intention to introduce a ‘points-based’ migration system from January 2021 that will align migration policy for EU and non-EU migrants. In this box we looked at the effect of the new migration regime on our borrowing forecast.

In Box 2.4 we described the new ‘points-based’ immigration system that the Government intends to introduce from January 2021, aligning the rules for EU and non-EU migrants.a Relative to the current regime, this is more restrictive for EU migrants but modestly less so for non-EU migrants. Successful implementation of the new regime by January looks challenging.

In our economy forecast, we assume that this reduces the size of the population and total employment in 2024-25 by 0.4 per cent as it reduces net inward migration. This reduction is concentrated among people on lower-than-average earnings reflecting the £25,600 salary cap, so the effect on nominal GDP in 2024-25 is smaller at 0.3 per cent.

In this box we describe how these changes have affected our fiscal forecast. This is a narrower question than the full fiscal impact of migrants that some bodies have sought to answer, since our forecasts take departmental spending plans set by the Government – we do not forecast the cost of providing, say, health services or education to the population. This means that lower net inward migration raises departmental spending per person, rather than reducing the total.

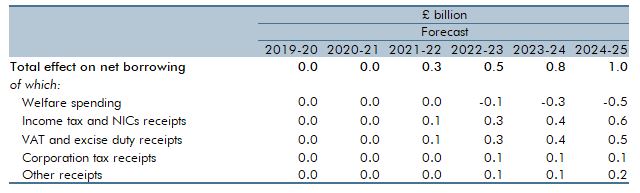

As Table D shows, the largest effects on our forecast are the savings from lower welfare spending that is offset by the cost of lower income tax and NICs receipts. With departmental spending fixed, the additional costs from lower tax receipts on consumer spending and on company profits means the overall effect on our forecast is to add to borrowing. For all but welfare spending and income taxes, we have calculated these effects by assuming that the reduction in nominal tax bases is broadly in line with the reduction in nominal GDP. For those two items we have modelled the effects at a more granular level:

- For welfare benefits, we have drawn on DWP and HMRC administrative data that matches nationality at point of application for a National Insurance number, tax, earnings and benefit records. It suggests that fewer than 10 per cent of existing EEA benefit claimants would have a salary above the £25,600 threshold. Savings from lower migration under this salary threshold build up to £0.5 billion a year by 2024-25, equivalent to 0.4 per cent of working-age and child welfare spending in that year. (This means that the Budget announcement tightening migrants’ access to benefits saves little as most of the benefit spending on this group ceases as a result of the migration regime.)

- For income tax and NICs, we estimate the effect of lower migration on wages and salaries based on the reduction in the size of the workforce and average earnings under the salary cap – this is a reduction of 0.3 per cent in 2024-25. We then calculate an effective tax rate on those lost earnings drawing on evidence from HMRC’s Survey of Personal Incomes. This yields a loss of income tax and NICs receipts that rises to £0.6 billion in 2024-25, equivalent to 0.1 per cent of the total in that year.

These estimates are necessarily a simplification of what can be expected in reality and are subject to significant uncertainty. In particular, they focus only on those who would not qualify to come to the UK because they are below the income threshold. They do not take account of the potential deterrent effect of the new system on those above the income threshold (who would still incur extra costs and hassle to move to the UK), where losses would be larger. Nor do they take account of initially low-income migrants’ earnings rising during their time in the UK.

Table D: The effect of the new migration regime on our borrowing forecast

Alongside the Migration Advisory Committee’s (MAC) latest report, Oxford Economics updated its analysis of EU migrants’ fiscal contribution. This sought to answer the broader question than the one we answer in this box, including the cost of providing public services.b It estimated the net fiscal contribution of those who would be ineligible under a salary threshold of £30,000 – as the MAC had been asked to consider – to be minus £2,200 a year. The report also showed that the net fiscal contribution moved from negative to positive at a salary of around £20,000 (depending on age), so the net fiscal contribution of those below a £25,600 cap would be more negative than £2,200 a year. The difference between Oxford Economics’ finding that cutting out such migration would boost the public finances and the negative effect the new migration regime change has had on our forecast reflects the fixed departmental spending totals. If departmental spending were 0.4 per cent lower in 2024-25, spending would be £2.0 billion lower, turning the negative impact on our forecast into a positive one.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2020