The Asset Purchase Facility (APF) houses the assets purchased by the Bank of England as part of its programme of quantitative easing. This box explained how this lowered interest rates benefitting the Treasury by £113 billion to date but it also increased the sensitivity of interest payments to future rate rises. The box showed how the cash flows to and from the APF change under various scenarios.

The Asset Purchase Facility (APF) houses the assets (predominantly gilts) purchased by the Bank of England as part of its programme of quantitative easing initiated in 2009. QE has had a variety of impacts on the public finances, for example: indirectly through its impact on the wider economy; through lowering yields on government debt; and through shortening the effective maturity of the consolidated public sector’s liabilities. This shortening of maturity arises as Bank reserves (floating rate debt) have been used to purchase gilts (long-term fixed-rated debt). This has increased the short-run sensitivity of debt interest payments to rate rises. To date, the APF has benefitted the Treasury (which receives the cash surplus) as the higher rates on longer-dated debt have meant that the payments on the additional reserves have fallen far short of the payments on the associated gilts. Our March forecast shows the APF paying £0.6 billion in 2022-23 on the £875 billion reserves issued by then to finance gilt purchases (a rate of under 0.1 per cent), but receiving £17.2 billion on the purchased gilts (a yield of 2.0 per cent). This reduces overall public sector interest payments to the private sector (and therefore the deficit) by £16.6 billion. To date, positive cash flows from the APF to the Treasury have totalled £113 billion.

It should be noted, though, that despite the large direct reduction in debt interest costs associated with the APF (reducing the effective interest rate by about 0.8 percentage points), the total fall in debt interest costs over the past decade is much larger (4.1 percentage points). The overall fall reflects lower Bank Rate and a flatter yield curve, in part a consequence of quantitative easing.

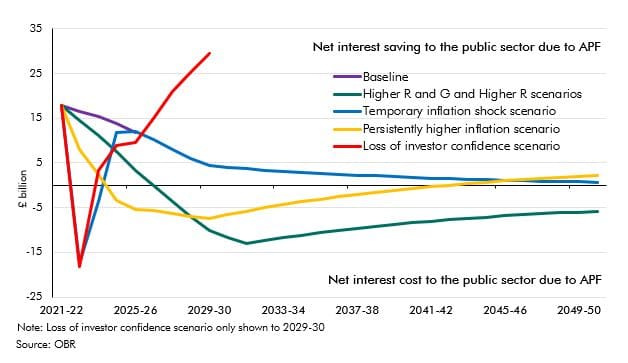

In the scenarios used in this chapter, we hold the size of the APF constant. Changes to Bank Rate (quickly) and the rate paid on gilts (more slowly) alter the ‘wedge’ between the APF’s interest receipts and payments. In the baseline, net interest savings gradually decline, at first largely because Bank Rate rises and then as gilts mature and are rolled over at lower rates (Chart D).

In the ‘higher R’ and ‘higher R and G’ scenarios, a rising Bank Rate sharply increases payments on reserves reducing the cash surplus of the APF and by 2026-27 these payments exceed the coupon income earned and so the APF shows a deficit. Gradually, as gilts are rolled over at higher rates, these losses diminish. The ‘persistently higher inflation’ scenario shows a similar pattern, though here, gilt rates rise far enough that eventually the APF returns to surplus.

Under the ‘temporary inflation shock’ scenario, sharp increases in Bank Rate quickly send the APF into deficit. But as the rise in Bank Rate is only temporary, after a few years the APF returns to surplus. At the start, the ‘loss of investor confidence’ scenario is similar, but here the surplus keeps rising as the soaring gilt rate rapidly increases earnings on rolled over gilts.

Chart D: Net savings to the public sector of the APF in our scenarios

In practice, were inflation pressures to pick up markedly, the MPC might choose to reduce the size of the APF rather than relying solely on Bank Rate to tighten monetary policy. This would be consistent with the MPC’s current guidance that it “intended not to reduce the stock of purchased assets until Bank Rate reached around 1.5%”,a though the Governor has noted that this guidance is currently under review. This would have several effects on the APF:

- Bank Rate would need to rise less in order to meet the inflation target, resulting in a larger surplus/smaller deficit.

- The smaller size of the APF would correspondingly reduce the size of future surpluses or deficits.

- Gilt sales would be likely to take place at a lower price than was originally paid, leading to a cash loss (on the assumption that sales only take place once Bank Rate has exceeded 1.5 per cent), which, under the Government’s indemnity on the APF, would be made good by the Treasury. Such trading losses could potentially be large: as of April 2021, selling all gilts in the APF portfolio at par would crystallise a trading loss of £114 billion.

The extent to which APF sales could substitute for increases in Bank Rate will depend on how fast

sales could take place. In practice a run-down is likely to take several years, as the MPC has

indicated that any reduction in the stock of assets will be at a “gradual and predictable pace”.b

In principle, the Government could cover any reduction in the cash flow from the APF by raising taxes, reducing spending, or increasing borrowing. Commentators have also advanced several alternative suggestions for mitigating the reduction in cash flow itself:

- Lowering (possibly to zero) the interest paid on reserves.c This is economically equivalent to maintaining the existing arrangements and introducing a new tax on banks related to their reserve holdings. Also, because it would increase the opportunity cost of holding reserves relative to other assets, it would change the nature of the monetary transmission mechanism and force the Bank of England to change its technique of managing short-term interest rates. It would also divert financial flows from banks to other less transparent channels.

- Require banks to hold some minimum level of reserves but pay a low or zero interest rate on them, paying Bank Rate on only the excess.d This would maintain the effectiveness of Bank Rate as a monetary policy tool, but would not avoid the consequences for banks’ profitability of acting like a tax on reserve holdings.

- Delaying the fiscal consequences of higher interest rates, for example by exchanging some of the reserves for short-maturity gilts.e This would reduce the speed with which interest rate changes fed through to spending, but would come with increased funding risk, since reserves do not need to be rolled over whereas the new securities would.

In conclusion, a tightening in monetary policy is likely to result, one way or the other, in a smaller contribution of the APF to the public finances. And though there are ways this could be mitigated, they each involve drawbacks of their own.

This box was originally published in Fiscal risks report – July 2021