We updated our 2011 analysis of fiscal drag on income tax and NICs to reflect new data, our latest assumptions and the effect of measures announced over the past year. This box outlined how fiscal drag effects income tax and NICs receipts and the long-term assumptions used.

HMRC have updated last year’s analysis of fiscal drag on income tax and NICs liabilities between 2016-17 and 2031-32. This is based on the latest Survey of Personal Incomes, updated long-term assumptions and the post-Budget 2012 tax regime i.e. incorporating the Budget decisions to increase the personal allowance and reduce the additional rate from 50p to 45p from April 2013. They find that by 2031-32, fiscal drag would increase tax revenues by 2.6 per cent of GDP (around 0.17 per cent a year). This is unchanged from last year’s FSR.

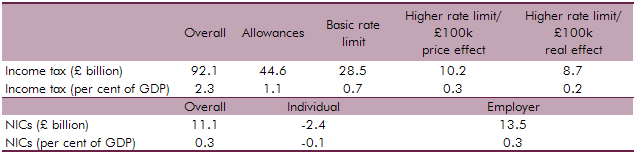

These estimates are generated by comparing two different scenarios on HMRC’s Personal Tax Model in which income tax and NIC thresholds and allowances are uprated either with CPI or nominal incomes. Of the fiscal drag effect on income tax:

- around half arises from individuals moving into paying tax and taxpayers paying a higher proportion of their income at the basic rate;

- around 30 per cent is from taxpayers moving into the higher rate band and existing higher rate taxpayers paying a larger proportion of their income at the higher rate; and

- the remainder is from the additional rate threshold and the personal allowance taper. The medium-term assumption is that these are fixed in cash terms, so fiscal drag arises from not uprating in line with CPI, let alone with incomes.

The fiscal drag effect on NIC liabilities is much lower. The effect is mildly negative for employee NICs since the marginal rate falls to 2 per cent above the upper earnings limit (currently £42,475). This is offset by the effect on employer NICs where there is no upper limit.

Table A: Income Tax and NICs: effect of fiscal drag (2017-18 to 2031-32)

Our long-term assumptions for uprating pensioner benefits are similar to the current medium-term policy settings. In both cases the Basic State Pension is subject to the triple guarantee (rising by the maximum of earnings, prices or 2.5 per cent a year), and the Pension Credit uprated with earnings. For the medium-term forecast, the Second State Pension is uprated by CPI in payment, but average earnings in accruals. Uprating other smaller pension benefits and non-pension benefits to pensioners, including housing and disability benefits, by earnings in the long term means that, in total, pensioner benefits would be 0.4 per cent of GDP higher in 2031-32 than under existing medium-term policy.

Nearly all working-age benefits are due to be uprated by CPI in our medium-term forecast. Our long-term assumption of uprating by earnings, which ensures that living standards for recipients are maintained relative to the rest of the population, therefore has a much larger relative effect on prospective spending, equivalent to 1.6 per cent of GDP by 2031-32. Both this and the corresponding figure for pensioner benefits are unchanged from last year’s estimates.

We also assume that student loan fees are uprated with earnings. The medium-term forecast assumes these are uprated with RPIX inflation from 2014-15, but rolling that assumption forward into the long term would imply that university income steadily diminishes relative to the size of the economy. If fees continued to rise in line with inflation, the impact on net debt from student loans would peak at only 5.5 per cent of GDP and tail off more quickly than in our central projections. In 2061-62 they would add 1.5 per cent of GDP to net debt rather than the central projection of 4.4 per cent of GDP.