Income tax was devolved to the Scottish Government in 2016 and policy changes since then have led to a divergence with the UK Government’s income tax system. In this box we explored the costing of the Scottish Government’s December 2023 decision to introduce a new 45 per cent ‘advanced’ rate and to raise the ‘top’ rate to 48 per cent, including the potential behavioural responses.

This box is based on HMRC and OBR data from March 2024 .

Scottish income tax was devolved in April 2016 and the policy changes made by the Scottish Government since then have led to the structure of the Scottish income tax system diverging materially from the rest of the UK. Rates and thresholds remained aligned for 2016-17. Since then, the Scottish Government has:

- Frozen the higher rate threshold (HRT) at £43,000 in 2017-18. Following further policy decisions since, the HRT in Scotland for 2024-25 will be £43,662 compared to £50,270 in the rest of the UK.

- Introduced two new bands in April 2018 – a ‘starter’ rate set at 19p and an ‘intermediate’ rate set at 21p. The higher rate was increased to 41p and the ‘top’ rate (previously the ‘additional’ rate) to 46p.

- Further increased the higher rate to 42p and the top rate to 47p, from April 2023 and reduced the top rate threshold to £125,140 in line with the UK Government.

- Announced, in its 2024-25 Budget, a new 45p ‘advanced’ rate, to apply to those with earnings between £75,000 and £125,140 (previously taxed at 42 per cent) and further increased the top rate to 48 per cent (previously taxed at 47p).

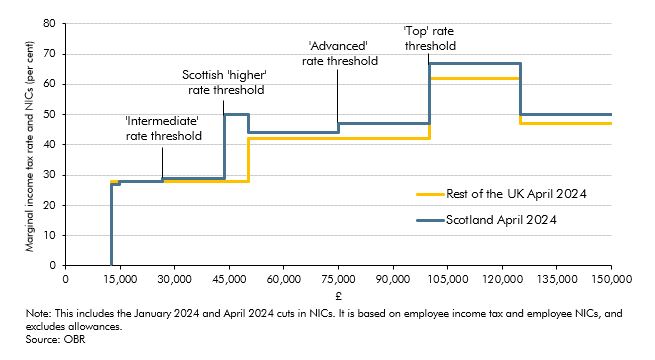

Chart 2.A shows the divergence in marginal income tax and NICs rates between the Scottish and UK tax systems for 2024-25, mainly explained by Scotland’s higher rates for the income tax intermediate, higher and top rates, and the lower HRT. a NICs rates and thresholds in Scotland and the rest of the UK are aligned.

Chart 3.A: Scottish and UK marginal income tax and NICs rates in 2024-25

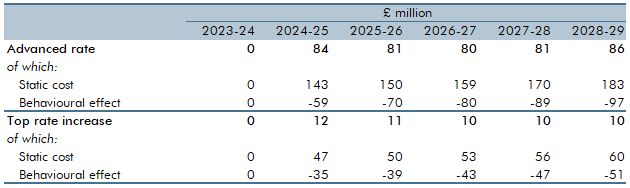

We estimate that the two measures announced in Scottish Budget 2024 raise a combined £93 million a year over the forecast period. Table 2.A shows that the static yield from the introduction of the 42p advanced rate and the increase in the top rate to 48p raises amounts that rise to £183 million and £60 million respectively by 2028-29. Around 60 per cent of the yield in 2028-29 is offset by behavioural effects, which can feed through several different channels:

- Individuals may decide to change the way they are remunerated to lower their tax liability, for example by increasing (or asking their employer to increase) pension contributions and/ or asking for additional salary. This might include those that would otherwise fall within the personal allowance taper range (those with earnings above £100,000, see Chart 2.A) where the close to 70 per cent marginal rate is a major disincentive. People may choose to reduce their working hours for similar reasons (and some may opt to not work anymore).b Individuals may choose to lower tax liability in other ways too, including incorporating, other tax-planning and tax avoidance. Some of these changes can take time, which helps to explain why the yield falls from 2025-26. The costing captures these

behaviours via the taxable income elasticities that are discussed below.c - It is also possible that there could be an intra-UK migration response with people choosing to move from Scotland to other parts of the UK. However, no separate migration effect is included in our estimate, as generally evidence suggests that the impact of tax changes on migration is very small.

- The expected scale of the behavioural response is more pronounced for higher earners, who have both more opportunity and incentive to adjust their taxable income. This explains the proportionately larger adjustment for the top rate measure.d

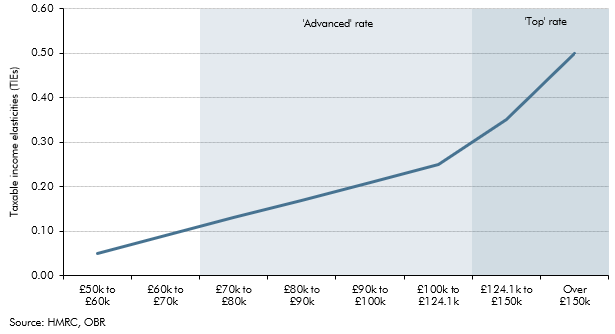

Table 3.A: Static cost and post-behavioural costings

Taxable income elasticities (TIEs) measure the responsiveness of taxable income to changes in the marginal tax rate. A higher TIE implies that the behavioural responses set out above will be larger. Numerous studies suggest that TIEs increase with income, i.e. higher-earners are more responsive to changes in tax rates than lower-earners.e Chart 2B shows the TIEs applicable to this costing. These TIEs were informed by a review of the literature, including HMRC’s estimate of Scottish taxpayers’ response to the 2018-19 policy changes described above.f The 0.5 elasticity for those earning over £150,000 was based on the taxpayers’ response to the UK Government’s 2012 decision to lower the additional rate (which applied at the time to those earning above £150,000) from 50p to 45p in 2013-14.g The chart also shows that those on lower incomes have relatively low TIEs due to several factors.h

Chart 3.B: Taxable income elasticities applied to this costing

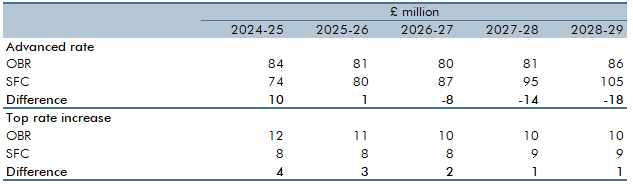

The Scottish Fiscal Commission’s (SFC’s) costing of the increase in the top rate is close to ours, while for the introduction of the advanced rate band rises it is around a fifth higher by 2028-29. (Table 2.B). The differences can largely be attributed to the static element of the costing, meaning it is therefore driven by our respective economic outlooks, including the path of earnings and the composition of the income distribution. The proportionate change in our respective costings that is due to behaviour is of a similar magnitude. The differences demonstrate the uncertainty inherent in all forecasts and policy costings.

Table 3.B: Comparing our costings to those of the SFC

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2024