Our 2021 Fiscal risks report explored the fiscal risks posed by climate change and the Government’s commitment to reduce the UK’s net carbon emissions to zero by 2050. This box examined the policies announced in the Budget, Spending Review, and Net Zero Strategy in October 2021, and the significant rises in market prices for hydrocarbons since we completed our Fiscal risks report, and how they had changed the risks associated with climate change and decarbonisation.

This box is based on OBR data from October 2021 .

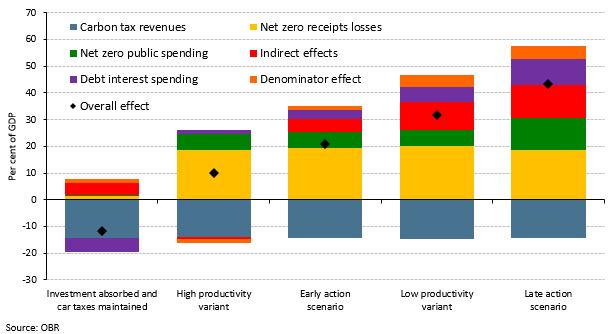

Our 2021 Fiscal risks report (FRR) explored the fiscal risks posed by climate change and the Government’s commitment to reduce the UK’s net carbon emissions to zero by 2050. We concluded that unmitigated climate change would ultimately have catastrophic economic and fiscal consequences for the UK. By contrast, while the fiscal costs of getting to net zero could be significant, adding around 21 per cent of GDP to public debt by 2050 in our ‘early action scenario’, they are not exceptional relative to the costs of other recent global shocks, such as the financial crisis and the pandemic. And there is a range of scenarios for getting to net zero, some of which could even improve the public finances over the next thirty years were the Government to accommodate net zero investment within its existing spending plans and find a replacement for declining fuel and other hydrocarbon revenues. We also concluded that acting early could halve the net fiscal cost of getting to net zero by 2050 compared to acting late (Chart C).

Chart C: Climate change scenarios: impact on public sector net debt in 2050-51

Since our FRR was published, the Government has released its long-awaited Net Zero Strategy (NZS), which provides a comprehensive plan for the UK to achieve net zero.a The Treasury’s accompanying Net Zero Review (NZR) provides additional analysis of the economic, fiscal, and distributional issues this raises.b Our FRR scenarios provided an illustration of what the long-term fiscal impact of getting to net zero could be, not what it should be. But it is nevertheless useful to consider how the cost of policies announced in the NZS, Budget and Spending Review compare with our own estimates and assess the residual risk to the public finances after these policies are taken into account.

In the Spending Review, the Treasury has estimated that net zero spending between 2021-22 and 2024-25 – spanning the 2020 and 2021 Spending Reviews – will total £25.5 billion, rising

from £4.4 billion this year to £7.7 billion in 2024-25 (from 0.4 to 0.7 per cent of total public spending). This down payment toward the overall investment cost of getting to net zero has been found from within existing spending totals (which saves some net fiscal costs relative to our central scenario which assumed all net zero investment was additional to existing plans).

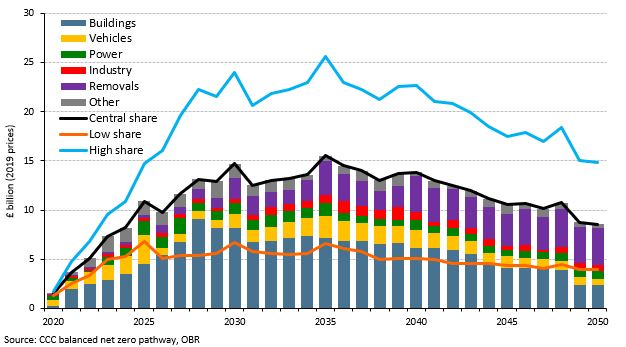

The £25.5 billion figure is broadly in line with the investment assumed in the early period of the ‘central spending variant’ of our early action scenario (Chart B), which was based on whole

economy cost estimates from the Climate Change Committee’s (CCC) ‘balanced net zero pathway’ and totalled £28.4 billion between 2021-22 and 2024-25. However, these estimates are not like for like in that:

- The Treasury’s investment estimates are the sum of amounts allocated to individual schemes funded in this and the previous Spending Review (plus the continuing cost of the Renewable Heat Incentive). As such, they reflect the gross investment allocated to spending on these activities (i.e. the purchase of an electric bus) and do not net off the amounts that would have been spent in a carbon-intensive counterfactual world (i.e. the purchase of a diesel bus).

- The CCC’s investment estimates used in our scenario relate to the marginal (additional) costs of decarbonisation over and above the costs that would have been incurred in a carbon-intensive counterfactual world (i.e. the cost of installing a heat pump over and above that of installing a gas boiler in the counterfactual).

In some cases, the Treasury figures will clearly be higher – the amount allocated to purchasing zero-emissions buses will exceed the marginal cost of purchasing them rather than diesel ones.

In others, the Treasury figures will be lower – £5,000 grants for domestic heat pumps being offered via the ‘Boiler Upgrade Scheme’ is less than the £10,000 marginal cost of installing one

relative to a gas boiler assumed in the CCC figures. The net effect of these differences cannot be calculated without knowing what counterfactual spending would have been in these areas.

Chart D: FRR scenarios for public investment in the transition to net zero

As foreshadowed in our FRR scenario, the decarbonisation of buildings is the largest recipient of net zero spending identified by the Treasury (at £9.7 billion it accounts for 38 per cent of the total over four years). In our FRR scenario, which assumed that the Government would cover all of the cost of decarbonising its own estate, plus half the costs of decarbonising the more than 28 million private residences with gas boilers and other fossil-fuel heating systems, the real terms cost of decarbonising buildings totalled £165 billion by 2050 (nearly half the total).

The FRR identified decarbonising domestic heating as a particular challenge (see Box 3.3). The Heat and Buildings Strategy,c published alongside the NZS, announced a ‘Boiler Upgrade Scheme’ that will provide £450 million in £5,000 grants to replace household gas boilers with heat pumps over the next three years.d If each heat pump cost £10,000, this would be sufficient to cover half the cost of installing around 90,000, decarbonising around 30,000 houses a year. But this represents one-twentieth of the 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028 assumed in the CCC’s balanced pathway – a figure endorsed in the Heat and Buildings Strategy itself. The Government expects 200,000 heat pumps a year to be installed in new build homes by 2027 (although it has yet to put in place the regulations to mandate this). It seems clear that this will remain a potential source of pressure on public spending for many years to come.

Public spending is not the only policy lever available to support the transition to net zero, with carbon taxes and regulatory levers among others that can be pulled. The NZS emphasises the use of public money to catalyse a private sector response. It aims to further incentivise this response with regulatory deadlines for phasing out petrol vehicles and coal-fired power plants. In addition, it documents several less-concrete goals for things like zero-emission aviation, the production of hydrogen fuel, and the ending of fossil-fuel boiler installations.

The Government made no firm statements concerning the revenue opportunities and challenges of climate change in the NZS, though it did note the potential for greater use of the UK Emissions

Trading Scheme. The Treasury’s NZR did, however, highlight the looming loss of 1.7 per cent of GDP (£37 billion in today’s terms) in revenue from fuel duty, VED and other high-carbon taxes, resulting from rising take-up of electric vehicles and other low-carbon technologies, and floated the option of extending carbon pricing.

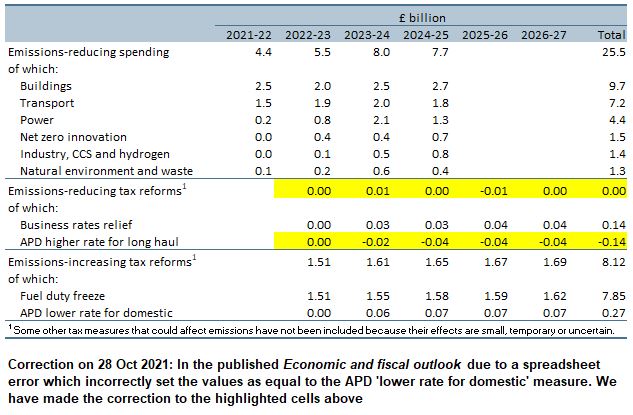

In addition, the Budget included several tax measures likely to reduce emissions, including:

- An expanded business rates relief for green energy equipment. This costs £140 million in the period to 2026-27. This cost does not reflect an explicit estimate of the behavioural response to the incentive it creates, with assumed growth in the tax base instead reflecting the NZS more broadly rather than isolating the effect of individual policy interventions.

- Reinstating a third band in air passenger duty (APD) for the longest long-haul flights. This raises £145 million in the period to 2026-27. It is assumed to result in around 23,000 fewer passenger journeys a year to destinations more than 5,500 miles away (a fall of less than 1 per cent).

But the Budget also included two more costly tax measures likely to increase emissions:

- The twelfth successive one-year fuel duty freeze. This costs £7.9 billion over the five years to 2026-27. Lowering the price of motoring in real terms is expected to increase fuel purchases over the next five years by 450 million litres (a 0.2 per cent increase).

- Introducing a lower rate of APD for domestic flights. This costs £275 million in the period to 2026-27. It is assumed to result in around 410,000 more passenger journeys a year (a 3.5 per cent rise), with that increase split evenly between genuinely additional flights taken and those displacing journeys that would otherwise have been taken by car.

From an overall fiscal perspective, as summarised in Table B, the Government’s Net Zero Strategy and Review, Budget, and Spending Review, make a material initial contribution to the

overall economy-wide investment costs of getting to net zero emissions by 2050. And while the Budget includes tax measures that could assist on the path to net zero, it also includes tax

measures that will make the job of getting there more difficult (and more expensive for the Treasury) by lowering the price of motoring and domestic air travel over the next five years. The

Government has not yet quantified the individual or net effect on emissions of these measures.

Table B: Emissions-related spending versus Budget tax measures

Of course, Government policy is not the only factor influencing the decisions that households and businesses make in respect of the transition to net zero. Market prices are constantly

changing too and the changes since our previous forecast in March have encouraged more rapid decarbonisation. Sharp rises in wholesale gas prices will reduce demand, with the

incentive felt more quickly for businesses than for households since they are not protected (temporarily) by a price cap. Similarly, higher traded carbon prices have significantly raised the

cost of carbon allowances issued under the UK Emissions Trading Scheme, revenue from which has trebled in 2022-23 relative to our March forecast, again discouraging higher-carbon activity

in the sectors it covers.

Taken together, the policies announced in the Budget, Spending Review, and Net Zero Strategy, and the significant rises in market prices for hydrocarbons since we completed our Fiscal risks

report in the summer, are likely to spur further reductions in carbon emissions and help to move the UK further along the path to net zero. But the whole economy costs involved in getting the

rest of the way by 2050 remain significant and their apportionment between businesses, households, and government beyond the next few years, remains largely unclear. This leaves the costs associated with the transition to net zero as a major source of longer-term fiscal risk.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2021