Cyberattacks are a growing global threat that, at the time of writing, had yet to cause sufficient disruption to national infrastructures to generate material economic and fiscal harm. We had not yet quantified the potential fiscal cost from cyberattacks, but included it in our Fiscal risk register for the first time. The box covered some of the potential types of cyberattack, their increasing prevalence and the mechanisms through which they might generate direct and indirect fiscal costs.

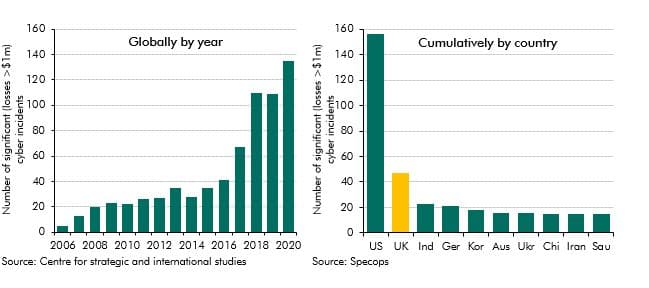

This box is based on Center for Strategic and International Studies, 'Significant cyber incidents since 2006', June 2021 and Specops, 'The countries experiencing the most 'significant' cyber-attacks', July 2020 data from and respectively.

One fiscal risk that we have yet to assess relates to cyber security and the UK’s resilience to cyberattack. Cyberattacks are a growing threat, but to date none have caused sufficient disruption to critical national infrastructures to have caused material economic and fiscal harm.a

But the relatively small scale of the damage of cyberattacks to date may not be a good guide to the risk of more significant harm being done in the future. They have been on a sharply rising trend (left panel of Chart A). On one measure, the UK is ranked in the top ten countries in the world in terms of global connectedness, so is arguably more vulnerable to cyberattacks by virtue of its role as a major global financial centre and the international reach of many of its companies.b Indeed, according to one study the UK suffered the world’s second highest number of significant cyberattacks between 2006 and 2020, behind only the US (right panel).c

Chart A: Significant cyberattacks since 2006

The UK Government’s National Risk Register places cyberattacks in its second highest ‘likelihood’ category, but in its second lowest ‘economic impact’ category, with attacks typically costing millions rather than billions of pounds. It warns that cyberattacks “can impact critical national services, and could cause a variety of real-world harm if services like the NHS are impacted”. The latter crystallised albeit modestly in 2017 with the global ‘WannaCry’ attack, which resulted in seven days of disruption across one-third of hospital trusts at a cost of £92 million.d

Cyberattacks come from a variety of sources including criminal and terrorist organisations, ‘hacktivists’, industrial spies and state-sponsored activities. The Chief Executive of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) has warned that state actors have been a constant presence in recent years, but that “for the vast majority of UK citizens and businesses, and indeed for the vast majority of critical national infrastructure providers and government service providers, the primary threat is not state actors but cyber criminals, and in particular the threat of ransomware”.e

The number of ransomware attacks has increased in recent years. On one estimate, over $400 million of payments were made by ransomware victims in 2020, with growth in recent years having been exponential.f In the UK, the NCSC reports that it handled three times more ransomware incidents in 2019-20 than in the previous year.g

Some recent attacks illustrate the potential for wider economic and fiscal consequences, though they were resolved before such effects crystallised. These include disruption to fuel supplies across parts of the US that could have resulted from the attack on the largest fuel pipeline in the US by the group DarkSide, and the hack on the US company SolarWinds, where malicious code inserted into the company’s network monitoring software affected 18,000 organisations across the world, the consequences of which may not be fully understood for many years.

Future cyberattacks could pose a major threat to the functioning of the global financial system, with an attack on one institution potentially spreading rapidly to others. To that end, the Bank of England is undertaking a cyber stress test for UK financial institutions in 2022.h Such attacks could pose material macroeconomic and fiscal risks. An IMF study estimates that average annual losses from cyberattacks on the financial system could be in the region of $100 billion globally, and in more severe scenarios might reach as high as $350 billion.i

The pandemic has also emphasised our reliance on digital technologies, which facilitated the rapid switch to working from home for large parts of the workforce, the accelerated shift to purchasing goods and services online, the Government’s design and delivery of unprecedented degrees of fiscal support to households and businesses, and rapid processing of welfare claims.

So while cyberattacks to date have had modest economic and fiscal implications, it is clear that they could pose a more material risk in the future. These could manifest themselves via some combination of: (i) disrupting public services; (ii) disrupting the collection of revenue or payment of benefits; (iii) disrupting payment systems or threatening financial stability, forcing government to step in and insure against or meet associated costs; and/or (iv) disrupting the critical national infrastructure on which the economy depends, like the power grid and transport network. These could result in various direct and indirect fiscal costs pushing debt higher.

As with our assessment of the fiscal risks from climate change in this report, it may be possible to build on the Bank of England’s 2022 cyber stress test to explore the fiscal risks from cyberattacks more fully in our next Fiscal risks report.

This box was originally published in Fiscal risks report – July 2021