Up to July 2022 the Bank of England's quantitative easing (QE) activities had made large profits resulting in large transfers to the Treasury but since then flows have reversed. This box described what the whole lifetime direct costs of QE would be based on our March EFO assumptions.

This box is based on ONS and OBR data from July 2023 .

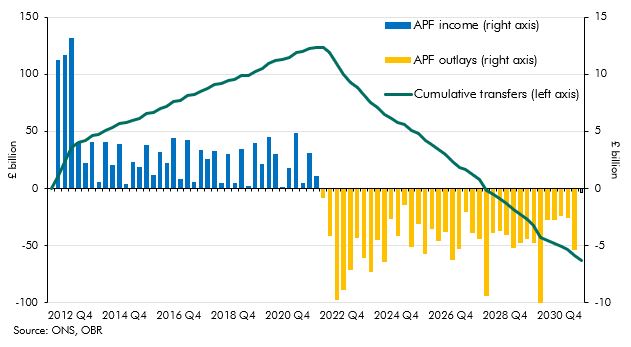

Since quantitative easing (QE), the purchasing of government debt and other assets financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, was introduced in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, central banks around the world have made large profits on these interventions. This is because the interest they paid on the reserves that financed QE asset purchases has been lower than the interest received on those assets for much of this period. In the UK, the cash profits of QE were originally retained inside the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF), but since the start of 2013 they have instead been remitted to the Treasury. As Chart A shows, up to July 2022, a cumulative total of nearly £124 billion was passed to the Treasury.

More recently, as Bank Rate and other market interest rates have risen and so market prices for government debt held by the APF have fallen, these profits have turned to losses, which are made good by transfers from the Treasury to the APF. These losses come from two sources:

- interest losses, as the variable rate paid on central bank reserves exceeds the fixed rates paid on the assets purchased (mainly gilts); and

- valuation losses, as the market value of gilts still held in the APF has fallen below the purchase value. These ‘mark-to-market’ losses do not crystallise until gilts are sold or redeemed.

From October 2022 to April 2023, £15 billion has been transferred from the Treasury to the APF to make up for losses. Under March 2023 Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) assumptions for Bank Rate and gilt yields, and for a constant £80 billion a year run-off of gilt assets,a losses are expected to continue over the remaining life of the APF eventually resulting in a cumulative net loss of £63 billion. The eventual lifetime net position is very uncertain and depends particularly on how gilt prices and Bank Rate evolve over an extended period. As an illustration, between early February when we took market determinants for use in our March forecast and early June, expectations for Bank Rate rose considerably and gilt prices correspondingly fell. Under these conditions overall losses might be £55 billion larger than under March 2023 EFO assumptions.

It is important to stress that this narrow summing of the lifetime cashflows associated with QE and quantitative tightening (QT) is not an assessment of the overall fiscal (let alone economic) impact of the QE programme, which supported the economy, asset prices, and financial markets at various points of stress over the past 15 years. The wider economic and fiscal benefits of these interventions would need to be taken into account in any comprehensive assessment of the impact of QE.

Chart A: Forecast of cumulative flows to and from the APF

This box was originally published in Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2023