The real-terms value of benefits was forecast to fall by around 5 per cent in 2022-23 (£12 billion in total) before catching up the year after, largely due to the significant rise in inflation and the lag in benefit uprating. In this box we compared these post-pandemic uprating dynamics to the real value of non-pensioner benefit rates following the previous three recessions. This showed that the forecast trough in the real value of benefits was deeper in the wake of the pandemic than for any of the previous three recessions.

This box is based on DWP and IFS data from January 2022 .

One of the most important drivers of changes in welfare spending over time relates to when, and by how much, the vast array of rates and allowances in the welfare system are updated – a process known as benefit ‘uprating’. Default policy settings typically see these uprated in line with a measure of inflation or earnings growth, but governments can choose to uprate most benefits by any amount, and often implement discretionary changes during and after recessions (as set out in Table 1.2 in Chapter 1). They can also choose to uprate benefits more frequently, which has been less common but happened most recently when the indexation of child benefit was brought forward from April to January 2009 during the financial crisis.a

Since the mid-1980s, the default for most non-pensioner benefits is that each year’s uprating is based on outturn inflation rates (as opposed to forecast rates of inflation for the year in question, which were often used prior to that).b Most rates and allowances in the non-pensioner welfare system are currently uprated each April by outturn CPI inflation from the previous September.

This means that there is a lag of up to 18 months in terms of how quickly benefit rates reflect changes in inflation in periods when it is rising or falling. This gives rise to temporary declines or increases, respectively, in the real living standards of (mainly lower-income) families as uprating takes time to catch up with inflation developments. Chart 2.5 in the previous chapter showed that while inflation was higher at the outset of all three previous recessions, and especially so in the early 1980s, the pandemic period stands out for seeing inflation rise very sharply in the post-recession years, from 0.6 per cent in the first quarter of 2021 to an expected peak of around 9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022 according to our latest forecast. (And to around 10 per cent in the more recent Bank of England forecast published on 5 May.c)

The precise timing of inflation changes this year and last is such that the lags to benefit uprating are particularly pronounced: benefits were uprated by 3.1 per cent this April – in line with last September’s CPI – but inflation began rising rapidly just after that and is forecast to average 8.0 per cent across fiscal year 2022-23 as a whole, meaning the real value of benefits falls by around 5 per cent, or £12 billion in total (including pensioner spending) this year. Our forecast assumes that benefits will rise by 7.5 per cent in April 2023 (our March forecast for the CPI inflation rate in September this year), whereas CPI inflation is expected to average 2.4 per cent in 2023-24 as a whole. So the real value of benefits is expected to rise by around 5 per cent in 2023-24 (£13 billion in total), largely restoring their real value after the dip in 2022-23.

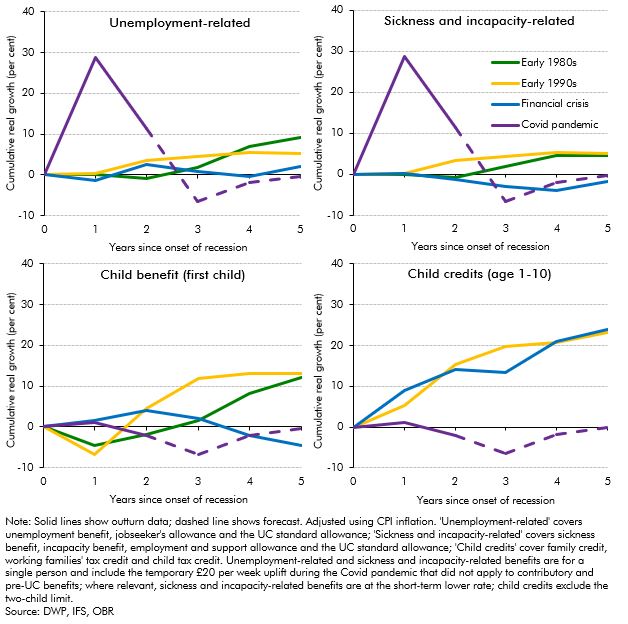

Chart A puts these post-pandemic uprating dynamics in the context of the previous three recessions, showing the real value of non-pensioner benefit rates for which we have comparable data across successive post-recession periods. For all four benefits, it shows that the forecast trough in the real value of benefits is deeper in the wake of the pandemic than for any of the previous three recessions, at 6 to 7 per cent lower in real terms by 2022-23, the third year after the start of the recession. (This trough would be around 8 per cent lower on the basis of the Bank of England’s latest inflation forecast.) And while all benefit rates are forecast to have almost caught up with their pre-recession real value by the fifth year of the pandemic (2024-25), they are in all cases lower than at the equivalent point following the early-1980s and early-1990s recessions. The comparison to the financial crisis is more mixed, with child benefit higher in the pandemic, child credits much lower, and unemployment- and sickness and incapacity-related benefits relatively similar. (The three-year 1 per cent cap on benefit uprating following the financial crisis began in 2013-14 – after the five-year period covered by our analysis – with the four-year benefit freeze that followed taking effect from 2016-17 onwards.)

Taking each benefit in Chart A in turn:

- Rates of unemployment-related benefits rose by almost 30 per cent in the first year of the pandemic, reflecting the £20-a-week uplift to the standard allowance in UC (which was also in place for half of the second year – 2021-22). This stands in contrast to the three prior recessions, when unemployment benefits roughly maintained their real value initially. The removal of the £20 uplift and the rise in inflation are expected to take unemployment benefits 6.6 per cent below their pre-pandemic real value in 2022-23. The drop in 2022-23 alone would represent the largest real year-on-year decline in the real value of unemployment benefits since annual uprating began fifty years ago (whether or not the removal of the £20 uplift is captured – the decline is 16.1 per cent including this and 4.5 per cent without it). Rates of unemployment-related benefits then recover their pre-recession real value over the fourth and fifth year following the pandemic, in contrast to the early 1990s and particularly the early 1980s, when the real value rose modestly (due, for example, to over-indexation in 1982 and 1983 to reverse previous declines,d and the fact that RPI – historically used to uprate benefits – was often higher than the CPI-based series we use to express benefit rates in real terms here).

- Trends in rates of sickness and incapacity-related benefits are similar to those for unemployment-related benefits, with the £20-a-week uplift for UC recipients again dominating in the early years of the pandemic before its removal and rising inflation temporarily eroding real benefit values. The slightly weaker trend for the financial crisis reflects the move from incapacity benefit to ESA over this period, in which rates were limited and aligned with those for unemployment-related benefits.e

- Child benefit rates (for the first child) fall in real terms in the third year of the pandemic (2022-23) reflecting the time-lag in relation to rising inflation described above, before recovering their real value over the following two years. This stands in contrast to the early-1980s and early-1990s recessions, when the real value of child benefit declined in the first year before rising steadily (thanks to a policy choice to raise child benefit in the early 1990s, detailed in Table 1.2 in Chapter 1), and to the financial crisis, when the real value rose initially (again driven by policy choices) before falling back to below where they are currently expected to reach five years on from the onset of the pandemic.

- Rates of child credits (for younger children) follow a similar decline-then-recovery pattern to that for child benefit during the pandemic. This is in marked contrast to the early 1990s and the financial crisis, when decisions to increase the generosity of these credits more rapidly raised their real value by over one-fifth in the fifth year of each recession, relative to the pre-recession value. During the financial crisis, increases in the child element of child tax credits were the key welfare policy measure to support families on lower incomes.

Chart A: Real value of selected benefit rates following recessions

This box was originally published in Welfare trends report – May 2022