In the years following the financial crisis the euro area faced a sovereign debt crisis characterised by high government debt, poor confidence in sovereign solvency and rising risk premiums on government securities. This box considered the main channels through which an intensification of the crisis could affect the UK economy, including weaker trade, tighter credit conditions, higher domestic government borrowing costs and possible financial system impairment.

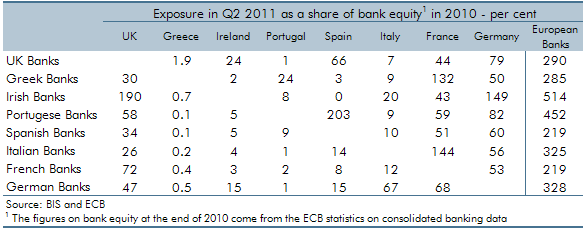

This box is based on BIS equity and ECB bank equity data from October 2011 and October 2011 respectively.

Since our March 2011 forecast, the euro area sovereign debt crisis has rapidly intensified. Our forecast is conditioned on policy makers finding a way through the current crisis over the next two years. Consistent with this view, we expect the spread between the prices UK banks pay for funding and the rates at which the government can borrow to start narrowing in 2012 and to stabilise by 2014, as shown in Chart 3.13.

The possibility of a more disorderly outcome represents a significant downside risk to our forecast, but one that is impossible to quantify in a meaningful way given the range of potential outcomes. (The Bank of England took a similar view in its August and November 2011 Inflation Reports.) That said, the main channels through which an intensification of the crisis could affect the UK economy are:

- trade – the euro area accounts for a significant share of UK exports, so additional weakness in euro area demand could lead to lower UK export growth. We explored some implications of this in the ‘weak euro’ scenario in our March 2011 EFO, which focused on the trade effects arising from sterling appreciation. Lower euro area growth and stronger sterling were shown to weaken UK output and employment. The impact depends on which euro area countries are most affected and whether monetary policy is able to offset the effects on domestic demand in the UK;

- tighter credit – recent developments have increased the funding costs faced by European and UK banks. This reflects a combination of direct exposure to stressed assets and indirect exposures arising from links between financial institutions. Table A shows that UK banks have relatively large direct exposures to euro area countries such as Spain, France and Germany. If the crisis is not resolved, then higher funding costs could bear down for longer on activity in the wider economy. We explore this possibility in our ‘persistent tight credit conditions’ scenario, presented in Chapter 5;

- government borrowing costs – UK gilt yields are currently at historically low levels, which is likely in part to reflect market perceptions that UK gilts are low risk relative to many euro area countries. It is not clear whether a further deepening of the euro area crisis would reduce gilt yields or increase them. In Chapter 5 we provide sensitivity analysis of the impact of higher and lower gilt rates on the public finances; and

- financial system impairment – a more serious escalation of the crisis, such as a disorderly default on sovereign debt, could put the global financial system under severe strain leading to tighter credit conditions, further depressing world output and trade. Negative feedback loops could emerge if weaker demand caused fiscal positions to deteriorate further. Given the range of potential outcomes from such an extreme event, it is not possible to quantify this risk in any meaningful way.

Table A: European bank exposure to selected countries