On 24 February 2022 the Government introduced a raft of changes to the working of the higher education student loans system in England. In this box we: summarised the reforms, explained their impacts on the complex accounting for student loans, and showed the overall impact on the latest forecast.

On 24 February 2022 the Government announced a raft of changes to the working of the higher education student loans system in England.a These ‘Plan 2’ loans represent the majority of student loan outlays in the UK (86 per cent in 2021-22). The Government also announced consultations into further potential changes to: focus financing on “high class provision”; reintroduce student number controls; and implement minimum entry requirements. Together these changes form part of the Government’s response to the 2019 Augar Review.b

We will analyse the long-run impacts of these changes in our Fiscal sustainability and risks report this summer. In this box we summarise the main reforms, explain their impacts on the complex

accounting for student loans, and show the overall impact on our latest five-year forecast.

The changes affect the system in four distinct ways:

- Freezing maximum tuition fees until academic year 2024-25 before reverting to rising by RPIX inflation.c By reducing higher education funding via the loan system this saves the Government money upfront and by reducing the amount owed by students it also reduces repayments in the longer term. But in the medium term, repayments are little affected since they are determined by graduates’ incomes rather than how much they owe.

- Reducing interest rates for new borrowers to equal RPI inflation (rather than up to RPI plus 3 per cent) with effect from 2023-24. This reduces the rate at which student debt rises due to accruing interest. The effect in the medium term is limited though as the ‘prevailing market rate cap’ is assumed to be in place for many borrowers up to 2024-25.

- Lower repayment thresholds. Thresholds for existing borrowers are kept at £27,295 to 2024-25 (the impact on our forecast includes an announcement on 2022-23 levels on 28 January) and then rise by RPI. For new borrowers, thresholds are reduced to £25,000 in 2023-24 and then held constant until 2026-27, and then also rise by RPI. These changes increase cash receipts modestly in the medium term, but this builds steadily over time ensuring much larger repayments over the life of the loans.

- Extending repayment terms to 40 years for new borrowers. This has no cash effect in the medium term, but by extending the repayment period from 30 to 40 years it increases lifetime repayments from borrowers that would have had loan balances written off after 30 years under the terms that will still apply to existing borrowers. In effect, affected borrowers will now pay a higher rate of income tax for their entire working lives.

Overall, reducing fees and interest rates reduces the total liabilities accrued by students. But by lowering repayment thresholds and extending the repayment term by a decade, borrowers in aggregate will pay a much larger share of the accrued liabilities reducing the share ultimately written off and borne by government. In terms of our fiscal forecast, this reduces the share of English loan outlays recorded as expenditure from 61 per cent in 2021-22 to 34 per cent in 2026-27. In terms of the ‘RAB charge’ recorded in the Department for Education’s accounts in respect of future write-offs, this reduces it from 57 to 37 per cent in 2026-27.d

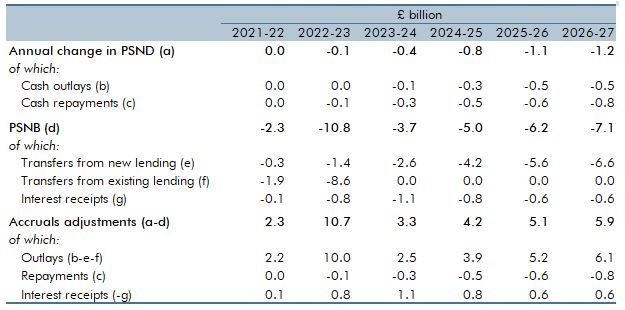

The recording of student loans in the public finances is complex. Total outlays are divided so that the share that is expected to be repaid (including both principal and interest) is recorded as a loan and the stock of these loans accrues interest, whereas the portion that will not be repaid is recorded as expenditure at the time the loan is made. As borrowers’ lifetime repayments increase and the total owed decreases, the transfer portion on new loans is lower, which reduces public sector net borrowing (PSNB) by amounts that rise to £6.6 billion in 2026-27 (Table A). The value to the Government of existing loans also improves (by £10.6 billion, thanks largely to lowering the repayment threshold). This is reflected in the public finances as a capital transfer received in 2021-22 and 2022-23 as the respective legislation is enacted. The stock of student financing counted as loan assets, rather than expenditure, therefore increases by £32 billion (1.1 per cent of GDP) by 2026-27 due to these changes. This larger stock of outlays treated as loans outweighs lower interest rates accruing on them to mean interest receipts are also higher.

Table A also sets out the changes to the cash flows that reduce public sector net debt (PSND) due to lower outlays (from lower fees) and higher repayments (from lower repayment thresholds).

PSND is reduced by modest amounts that total £3.7 billion by 2026-27. It also shows the reductions to PSNB from lower transfers to students and higher interest receipts, which are dominated by the implications of lower repayment thresholds. The PSNB effects total £35.1 billion over the same period – a much larger impact than that on debt, which reflects the fact that these represent the upfront accrual of substantial effects on distant future cash flows. The accruals adjustments show how the difference between PSNB and PSND is bridged in the public finances. These policies therefore affect all the flow and stock aggregates recorded in Chapter 3.

Table A: Fiscal impacts of policy changes to the student finance system

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2022