Box sets » Public spending

Unfunded pension liabilities represent the second-largest government liability after gilts, but are not included in the PSNFL measure of debt. In this box, we analysed the treatment of unfunded pensions in the National Accounts and the fiscal risks they create.

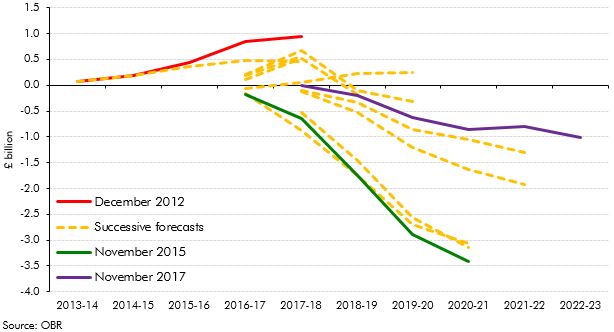

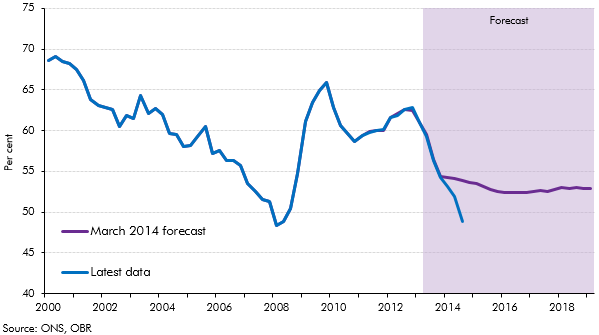

Public sector net debt (ex BoE) has risen substantially over the past 25 years, despite repeated government plans to get it falling. In this box, we examined the key drivers behind this upward trend, including the impact of major economic shocks, the persistent gap between forecasted and actual debt outcomes, and the increasing difficulty of stabilising debt due to structural fiscal pressures.

Our March 2023 fiscal forecast had a difference across other current spending of £14.9 billion, accounting for around 40 per cent of the £39.8 billion overall difference between the March 2023 spending forecast and outturn. This box explored explanations and set out which forecast methodologies we would review as priorities.

The Pathways to Work Green Paper announced a range of welfare measures, some of which we have not incorporated in this forecast. In this box, we explained why some measures were not included, and indicated what risks they pose to our welfare spending and labour supply forecasts.

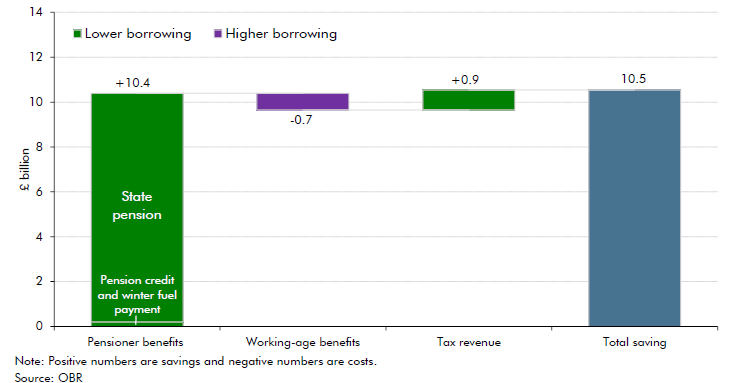

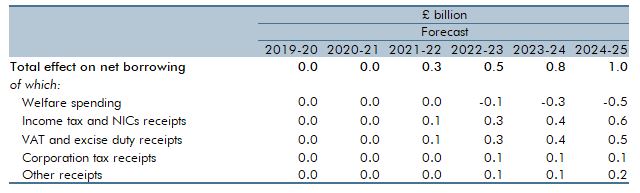

As life expectancy has increased, successive governments have increased the state pension age, and it next increases between 2026 and 2028 from 66 to 67. In this box, we estimated the impact of this increase on pensioner welfare spending, working-age welfare spending, and tax revenue.

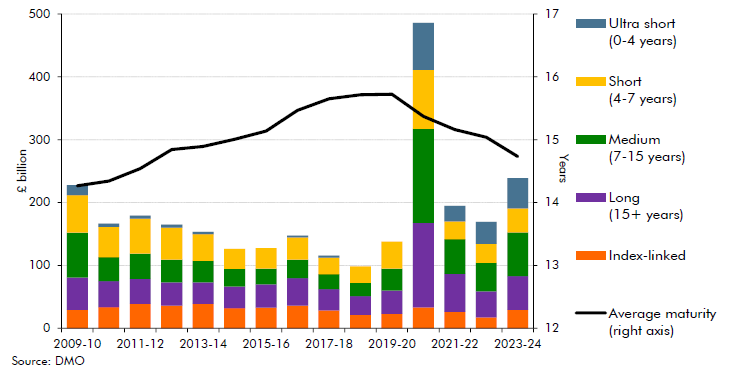

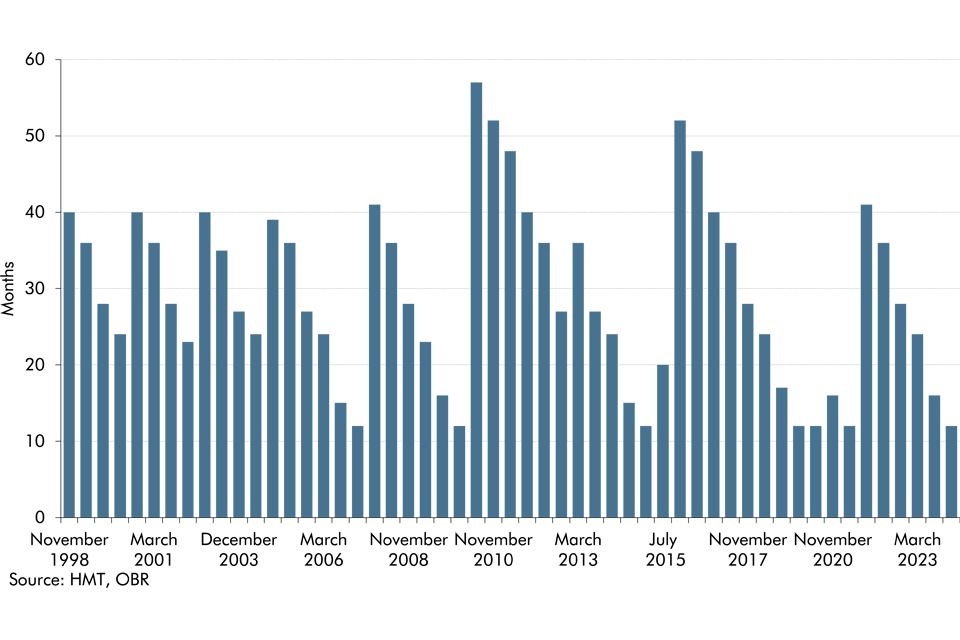

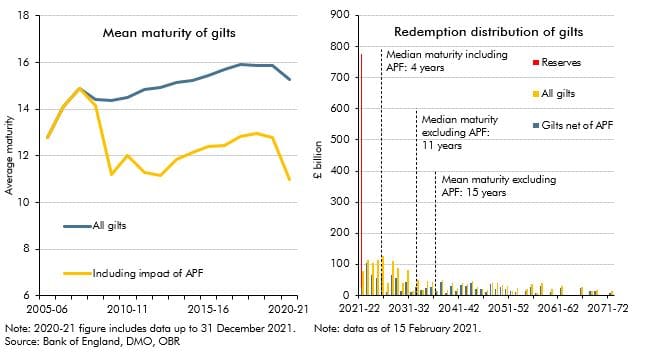

The UK government meets the bulk of its financing needs through issuing gilts across a variety of maturities. In recent years the average maturity of gilt issuance has fallen steadily, this box discussed the drivers of this change and the implications.

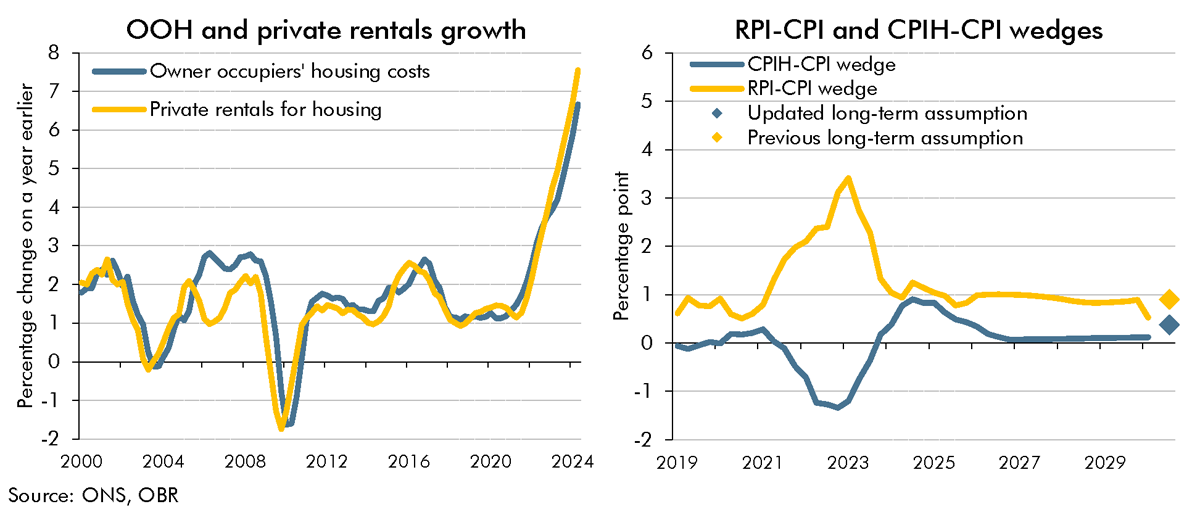

As as result of the shortcomings with the methodology for calculating the Retail Prices Index (RPI), the ONS's current plans are to address these by bringing the methods and data sources from the Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers' housing costs (CPIH) into the RPI in February 2030. In this box, we explained how this change would impact our estimate of the long-run difference between RPI and CPI inflation.

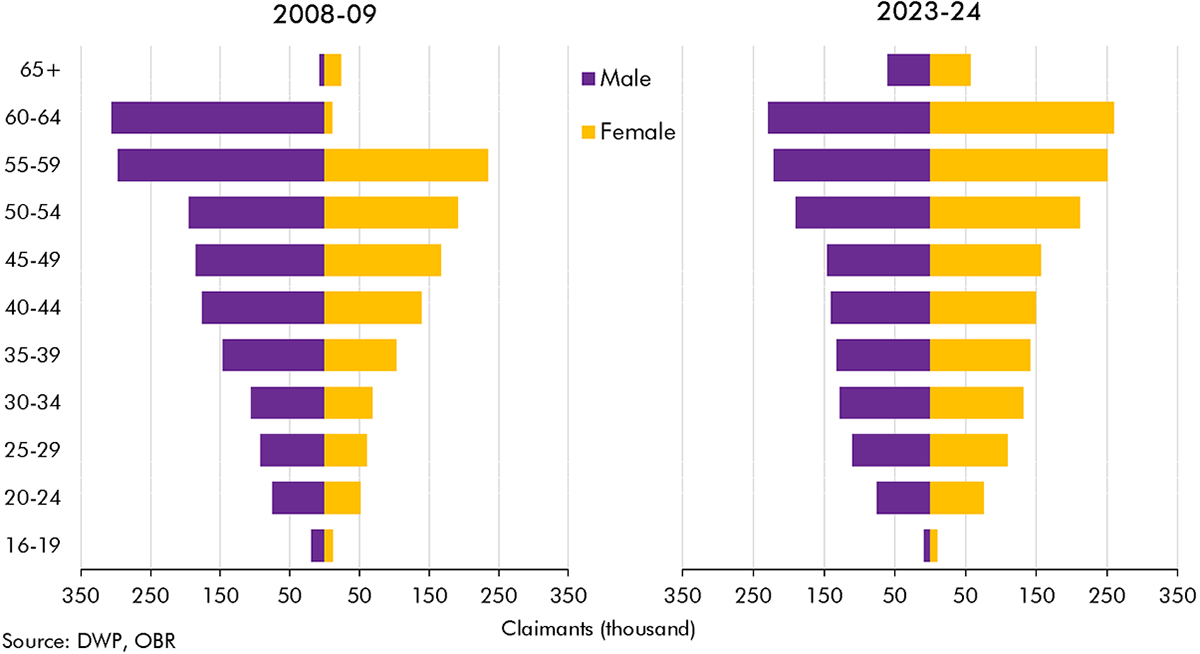

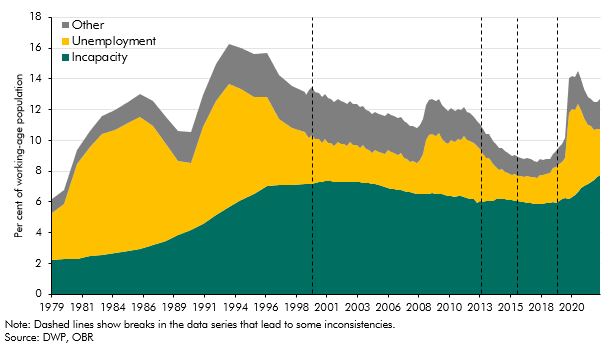

The rise in incapacity benefits after 2013-14 coincided with a rise in the state pension age. In this box we explained how much of the change in incapacity benefit caseload was explained by rises in the state pension age and the ageing of the population.

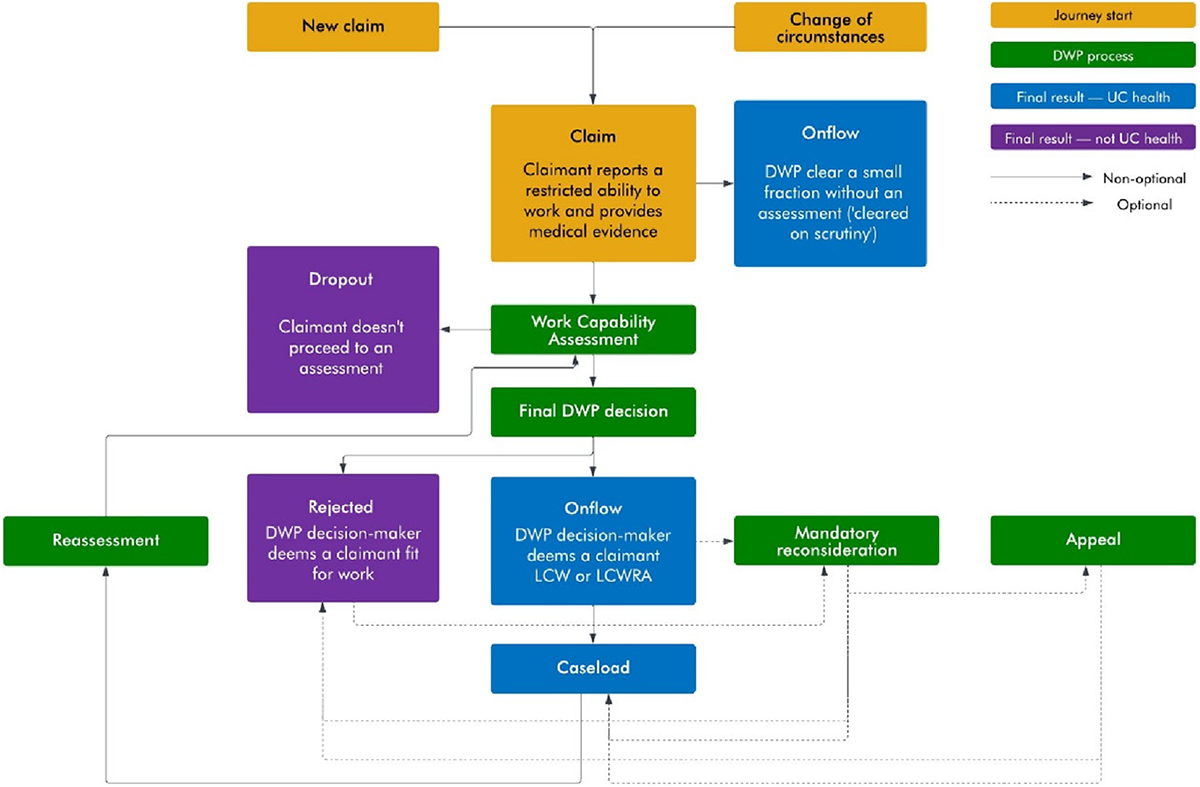

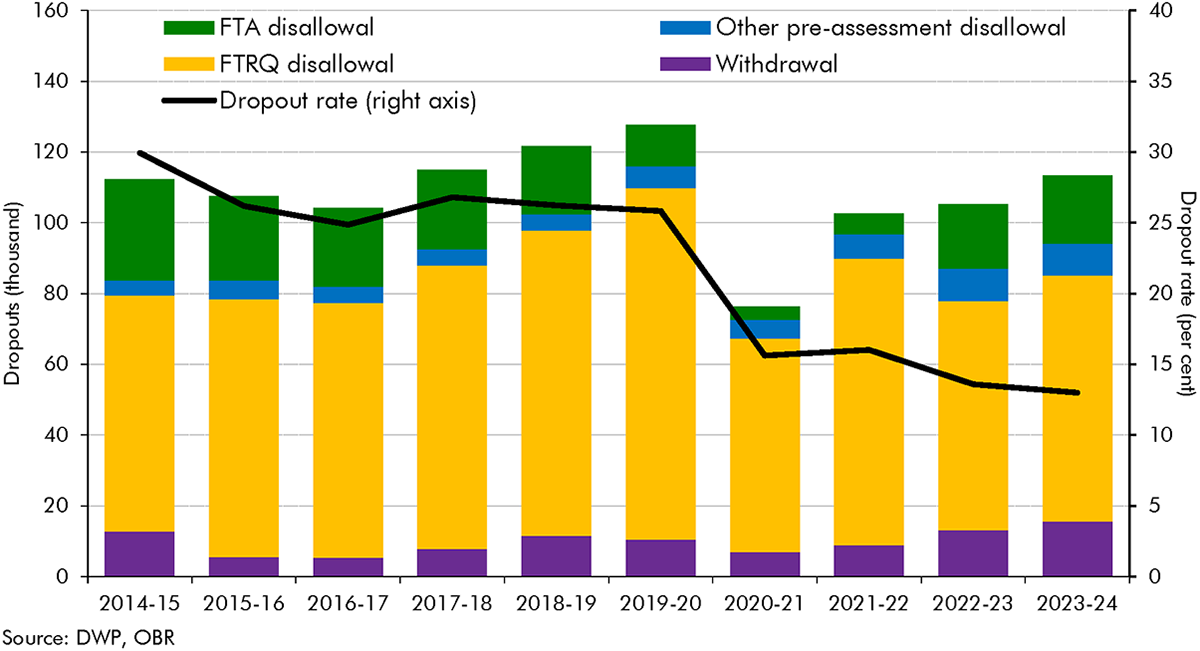

There are several stages before a claimant joins an incapacity benefit. In this box we explained the stages involved in joining either the less-severe (LCW) or more-severe (LCWRA) groups under universal credit, and differences in the predecessor employment support and allowance benefit.

Both incapacity and disability benefit onflows have grown substantially since 2018-19. In this box we compared the different drivers of these respective increases in onflows and drew some lessons from the granular disability benefit data for how incapacity onflows may have been changing.

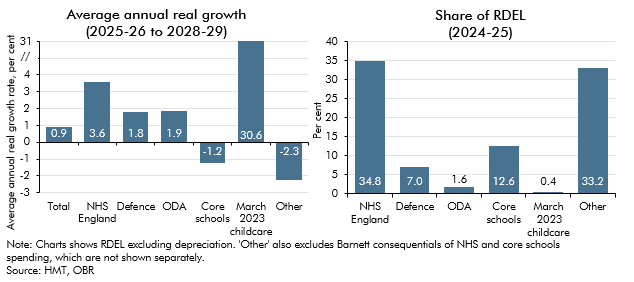

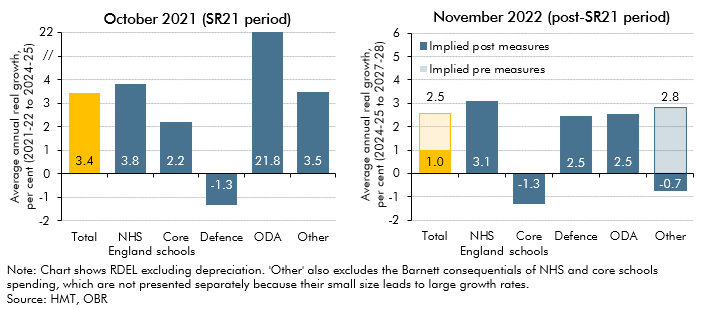

In the final four years of our March 2024 forecast, departmental spending follows an overall envelope set by the Government because the detailed departmental spending plans set at the last Spending Review only extend to March 2025. In this box, we explored the implications of these plans for different departments, and how past governments have revised departmental spending at Spending Reviews.

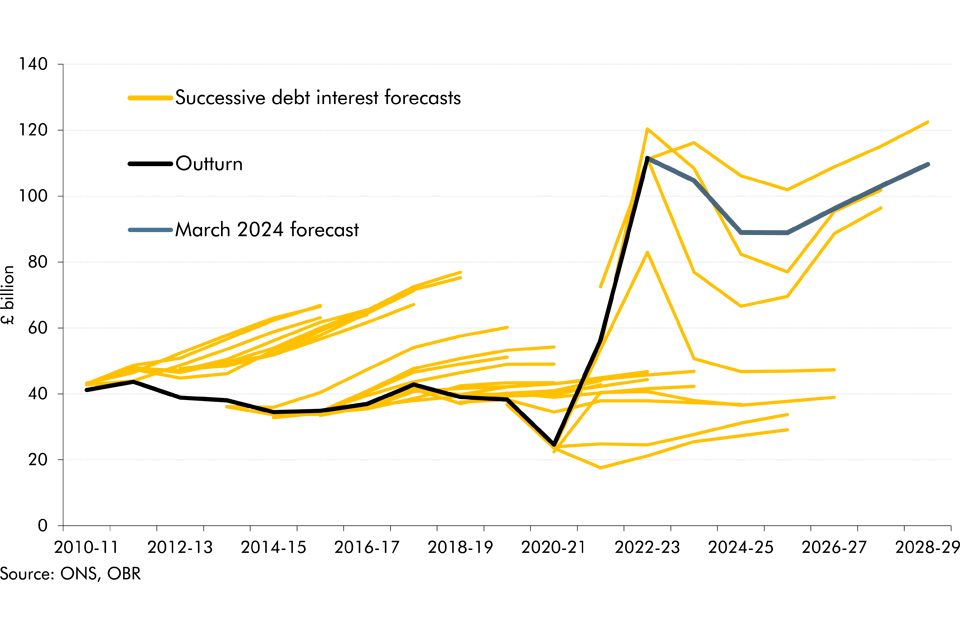

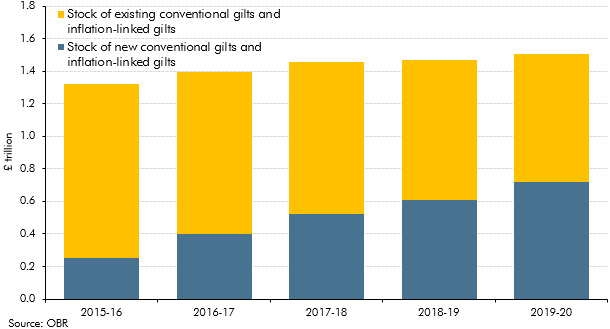

Debt interest spending has reached post-war records as a per cent of revenue and GDP in recent years and has also proved to be incredibly volatile and subject to large revisions between our forecasts. In this box we looked at the reasons for this elevated spending and volatility and how the process of quantitative tightening by the Bank of England will impact the maturity of this debt.

Benefits for working-age claimants with health problems have changed significantly over the last thirty years through the introduction of new benefits and assessments. This box described how the UK welfare system operates for working age claimants with and without health problems, and how this has changed over time.

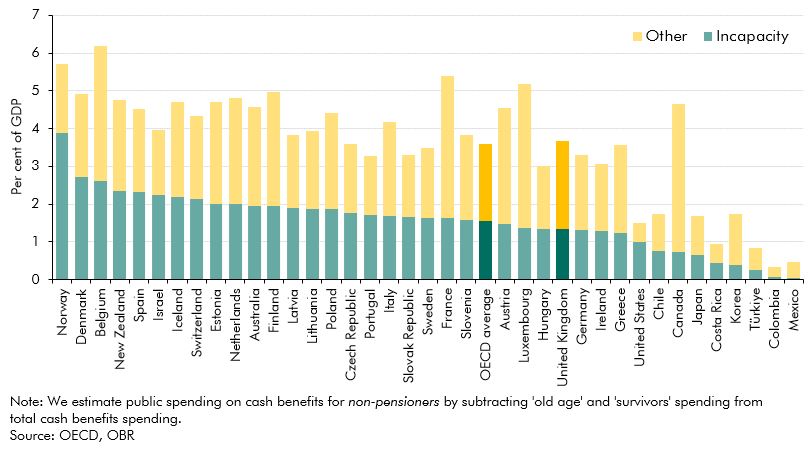

The UK spent close to the OECD average on non-pensioner cash benefits in 2019. This box compared the provision and generosity of health-related welfare across countries, drawing on several international studies.

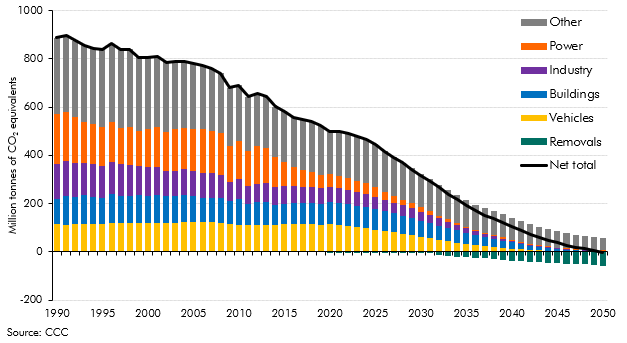

Since our 2021 Fiscal risks report - which showed that reaching net zero carbon emissions will have significant impacts on the public finances in the UK - estimates of the fiscal impacts of reducing emissions in other countries have begun to be produced. In this box we recapped our 2021 work and discussed how IMF and French analysis compared to it.

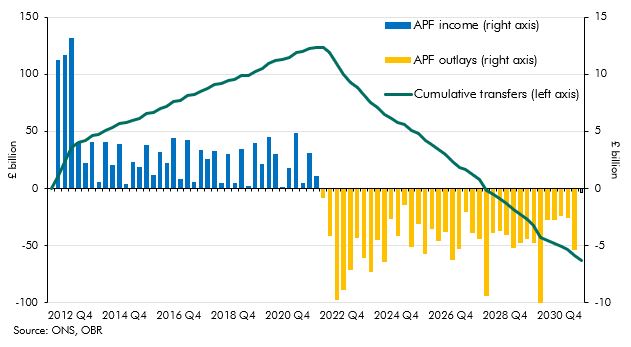

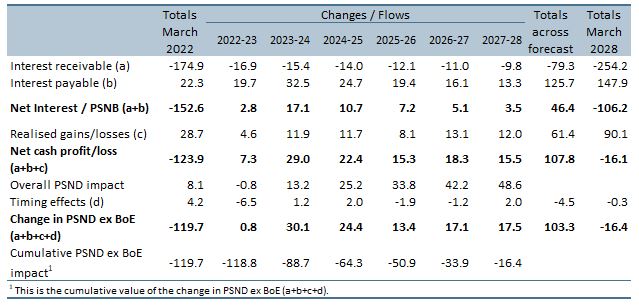

Up to July 2022 the Bank of England's quantitative easing (QE) activities had made large profits resulting in large transfers to the Treasury but since then flows have reversed. This box described what the whole lifetime direct costs of QE would be based on our March EFO assumptions.

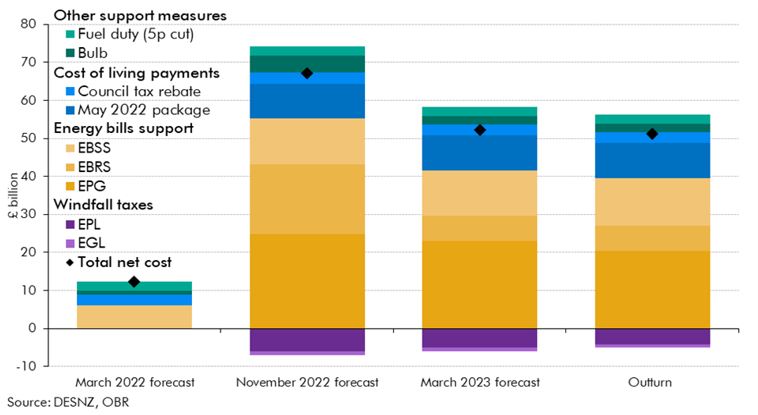

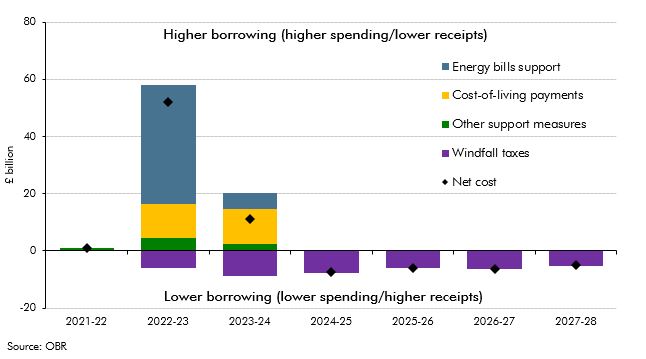

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 led to a surge in wholesale and retail energy prices, and a subsequent rise in inflation to a four-decade high. To support households and businesses, the Government introduced a series of policies during 2022 which were a key factor pushing spending and borrowing outturn in 2022-23 above both our March 2021 and March 2022 forecasts. This box examines how the costs associated with this policy response in 2022-23 evolved over successive forecasts and in initial outturn.

In the final four years of our November 2023 , departmental spending follows an overall envelope set by the Government because the detailed, department-by-department plans set at the last Spending Review only extend to 2024-25. In this box, we explored the implications of these plans for different departments.

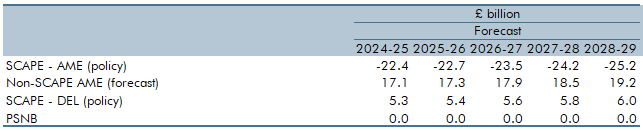

The new SCAPE discount rate, to be implemented in April 2024, increases the present value of future pensions payments and in turn causes employer contributions to rise. Box 4.4 explained the SCAPE rate change and its overall impact on the public finances.

In the March 2023 EFO we estimated that the policy package in response to the rise in energy prices would cost £78 billion in 2022-23 and 2023-24. This box assessed how the cost of the UK Government's response compares internationally.

In November 2021 the Government appointed administrators for Bulb Energy Limited and provided facilities to cover Bulb's financing needs. This box described how we accounted for transactions with Bulb in our March 2023 forecast.

The Bank of England's Asset Purchase Facility (APF) conducts the Bank's operations for quantitative easing and tightening. Following sharp rises in interest rates in 2022 the APF has started to make large cash losses. This box looked at the causes of those losses and how they feed through to fiscal aggregates.

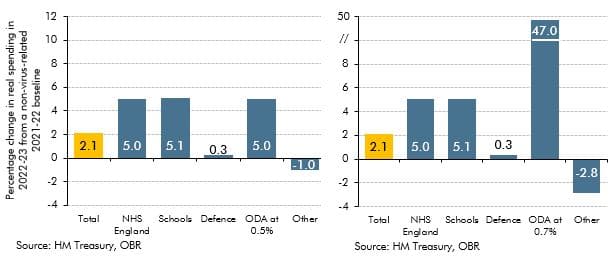

In November 2022 the government reduced its departmental (DEL) spending assumptions for the final three years of the forecast period. This box discussed the implications of the government's day-to-day and capital spending plans for various departments and public services during and after the 2021 Spending Review.

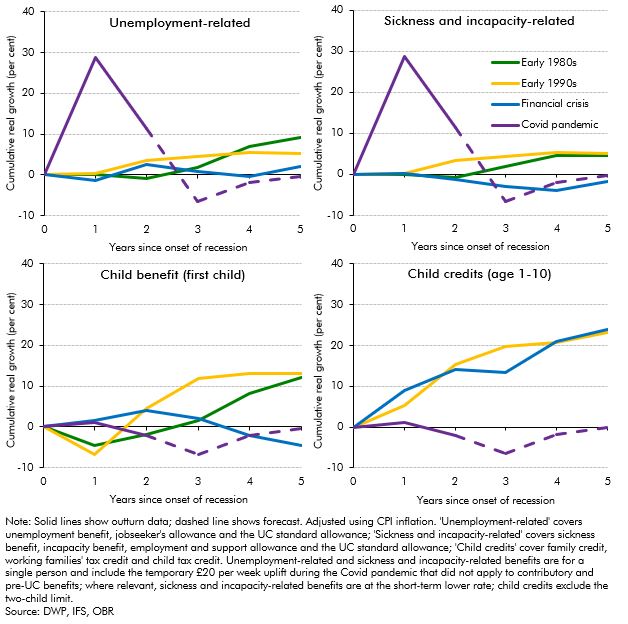

The real-terms value of benefits was forecast to fall by around 5 per cent in 2022-23 (£12 billion in total) before catching up the year after, largely due to the significant rise in inflation and the lag in benefit uprating. In this box we compared these post-pandemic uprating dynamics to the real value of non-pensioner benefit rates following the previous three recessions. This showed that the forecast trough in the real value of benefits was deeper in the wake of the pandemic than for any of the previous three recessions.

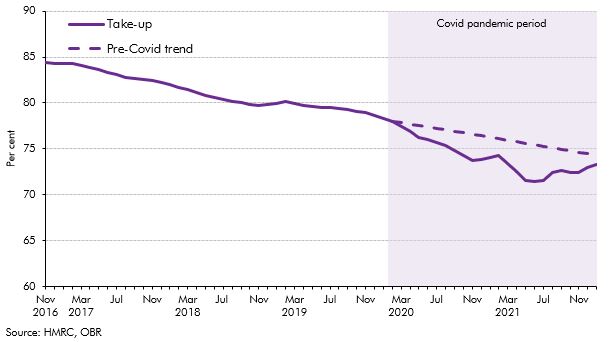

Take-up of child benefit had been declining since 2012-13, but this downwards trend accelerated at the onset of the Covid pandemic in March 2020, which resulted in a steep decline in take-up over the subsequent 18 months. In this box, we considered the main drivers of the child benefit caseload and the effect the pandemic had on each of them. We set out the reasons why the pandemic contributed to lower take-up, and then considered the medium-term impact of the pandemic-driven drop in take-up on our forecast.

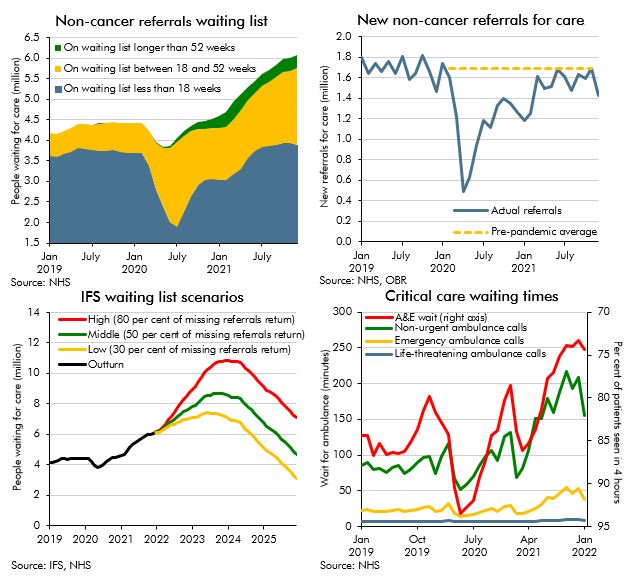

The NHS is the largest single item of public spending in the UK, and has been placed under extraordinary pressure as a result of the pandemic. Historically, some of the largest policy-related revisions have related to health spending, including the £13 billion a year announced at the 2021 Spending Review. This box explores indicators of pressure across the health service and the potential for these pressures to result in risks to our forecast.

The pandemic generated only modest structural damage to the fiscal position but did still create a gap in what the Chancellor considered a sustainable fiscal position. This box compared the scale of fiscal consolidation facing the chancellor and his approach to repairing the public finances with the challenge that faced Chancellor George Osborne after the financial crisis.

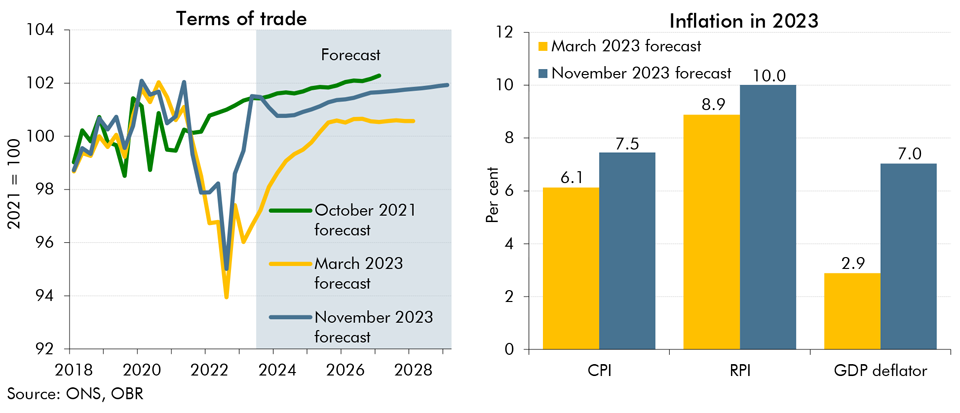

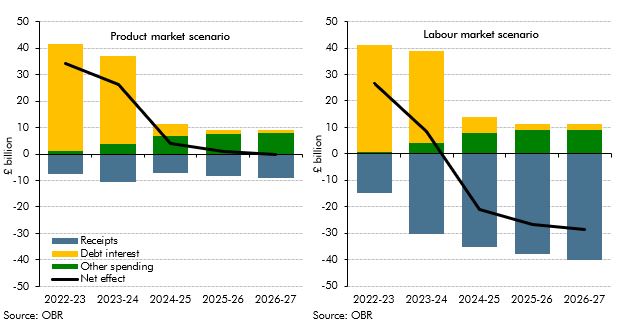

The level and nature of inflation has consequences for the public finances. This box explored the fiscal consequences of the sharp rise in inflation since our March 2021 forecast and examined the fiscal effects of the two scenarios described in Box 2.6 in our October 2021 EFO one where inflation is driven mainly by pressures in the product market, and the other mainly pressures in the labour market. The box concluded the labour market inflation scenario was significantly more beneficial for the public finances.

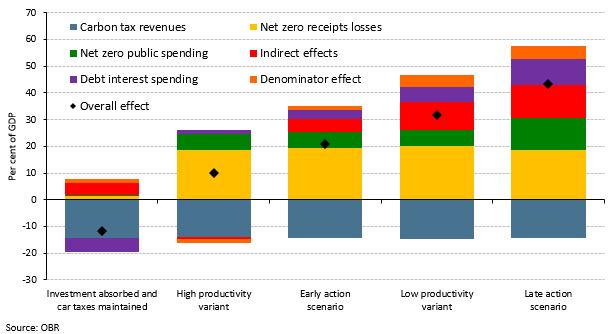

Our 2021 Fiscal risks report explored the fiscal risks posed by climate change and the Government’s commitment to reduce the UK’s net carbon emissions to zero by 2050. This box examined the policies announced in the Budget, Spending Review, and Net Zero Strategy in October 2021, and the significant rises in market prices for hydrocarbons since we completed our Fiscal risks report, and how they had changed the risks associated with climate change and decarbonisation.

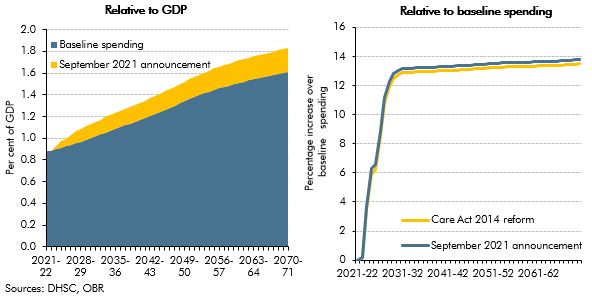

On 7 September 2021, the government announced a reform to the funding of adult social care in England. In this box, we described how this reform compares with the 2011 Dilnot Commission proposals and the reforms from the Care Act 2014 that were planned for April 2016 and then abandoned.

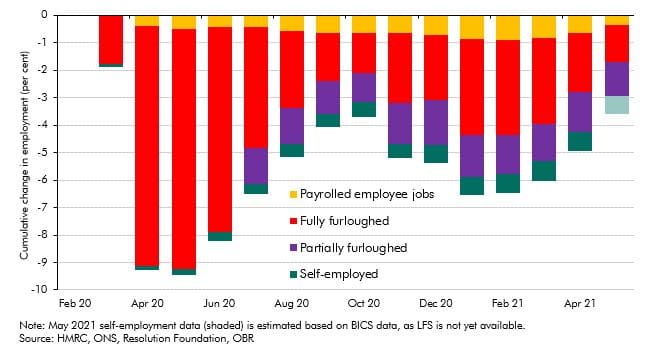

The Government announced in March 2021 that the coronavirus job retention scheme (CJRS) would be phased out completely by the end of September 2021. In this box, we looked at the latest evidence on the number of people on the scheme and their concentration in certain industries, as well as the latest data on vacancy rates. We also discussed how these data related to our labour market assumptions from March 2021.

One of the greatest challenges in achieving net zero in terms of both cost and technical difficulty will be to decarbonise the more than 28 million homes in the UK that rely on fossil fuels for heating (typically gas central heating) and are, for the most part, poorly insulated. In this box we examined the similarities and differences between the future transition of domestic heating and one of the past, that of the switch to natural gas over the decade to 1977.

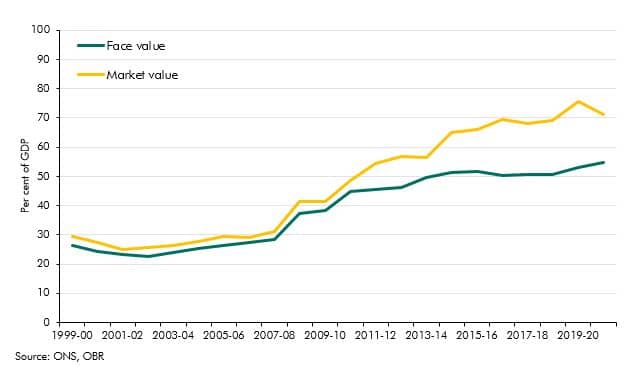

Government debt liabilities can be valued in various ways. In recent years market and face values have diverged sharply reaching 15% of GDP. In this box we explained why this has happened and why we use face value in our analysis.

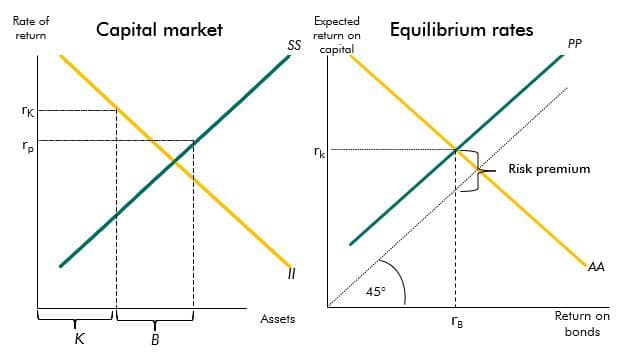

The yields on government debt have declined over recent decades. This box described a stylised model that provides a framework to explain the drivers of these changes.

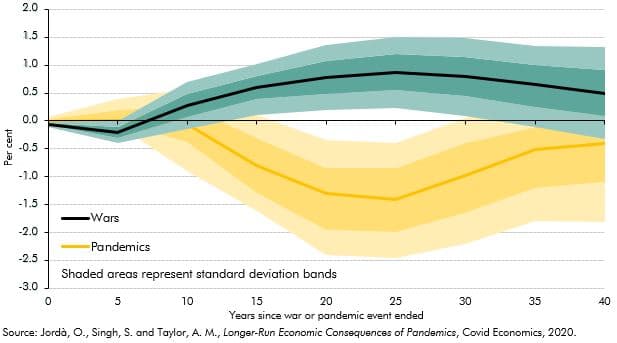

Past pandemics have had long-run impacts on real interest rates. A recent paper found that 20 years after a pandemic real rates fell by, on average, 1.5 percentage points (though less in the UK). This box examined the evidence for the current pandemic and suggested why this time it may be different.

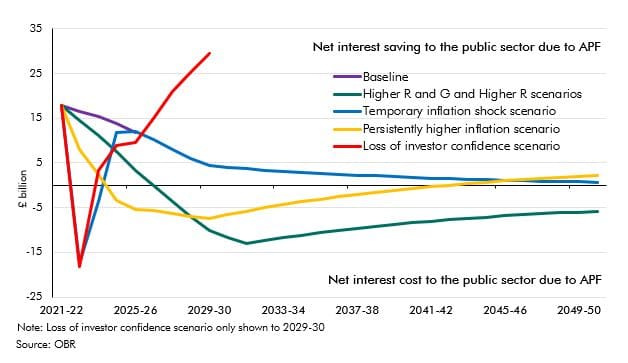

The Asset Purchase Facility (APF) houses the assets purchased by the Bank of England as part of its programme of quantitative easing. This box explained how this lowered interest rates benefitting the Treasury by £113 billion to date but it also increased the sensitivity of interest payments to future rate rises. The box showed how the cash flows to and from the APF change under various scenarios.

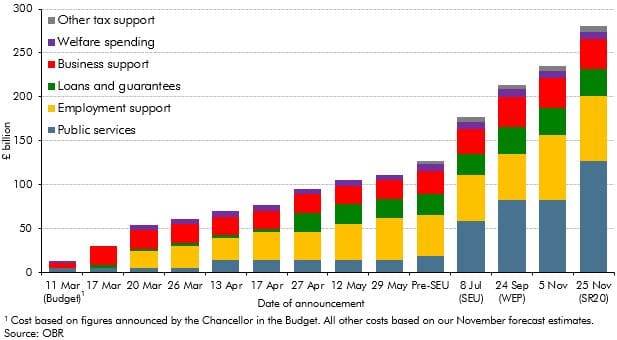

In the March 2021 EFO we estimated that policy measures responding to the coronavirus pandemic would add £344 billion to borrowing, with these policies announced across a number of statements beginning alongside the March Budget. This box updated on our estimate of this cost from November and the relative shares of support going to households, businesses and for public spending.

This box discussed the risks to our medium-term forecast of day-to-day departmental (RDEL) spending, particularly in relation to the impact of the pandemic.

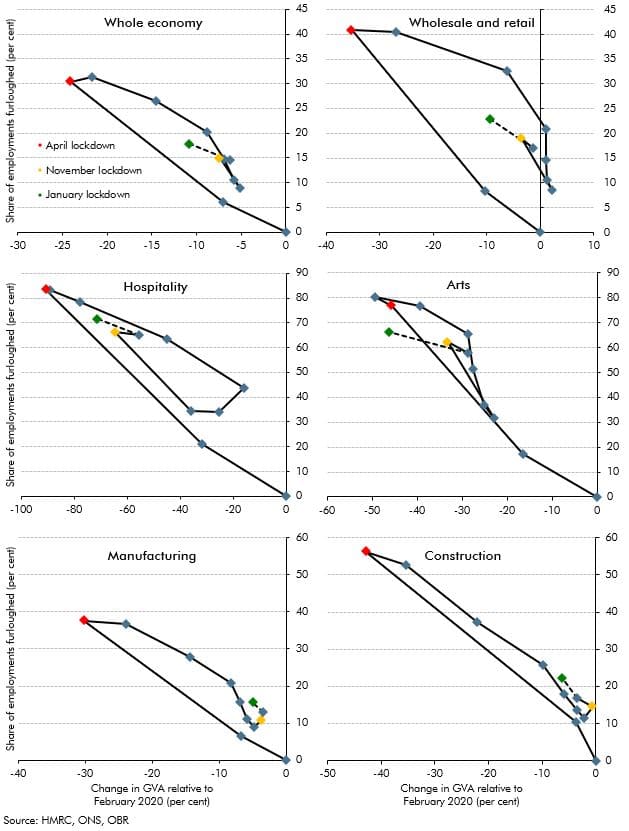

In this box, we discussed how the hospitality, wholesale and retail, arts, manufacturing and construction sectors, as well as the economy as a whole, adapted the usage of the furlough scheme in relation to output, and commented on the increased level of employees on furlough relative to the loss in output in the November 2020 and January 2021 lockdowns when compared with the April 2020 lockdown.

On 4 February 2021 the Government published its response to the December 2018 Court of Appeal ruling that the transitional protection arrangements in place across public service pension schemes based on years from retirement constituted a form of unlawful discrimination on the basis of age, commonly known as the ‘McCloud-Sargeant case’. This box explored the potential fiscal impacts of the Government’s remedy, as it was not possible to reflect the costs directly in our March 2021 EFO due to remaining uncertainty around the schemes’ implementation of the response.

The average maturity of UK government bonds is longer than the average maturity of government debt in most other advanced economies. But the average maturity of the net debt of the public sector as a whole (including the Bank of England) has shortened considerably since the global financial crisis. In this box, we explored how the Bank of England's quantitative easing operations have shortened the maturity of public sector net debt, dramatically increasing the sensitivity of debt interest spending to changes in short-term interest rates.

In the November 2020 EFO we estimated that policy measures responding to the coronavirus pandemic would add £280 billion to borrowing in 2020-21, with these policies announced across a number of statements beginning alongside the March Budget. This box considered the main statements contributing to this cost and the nature of the support included in these announcements.

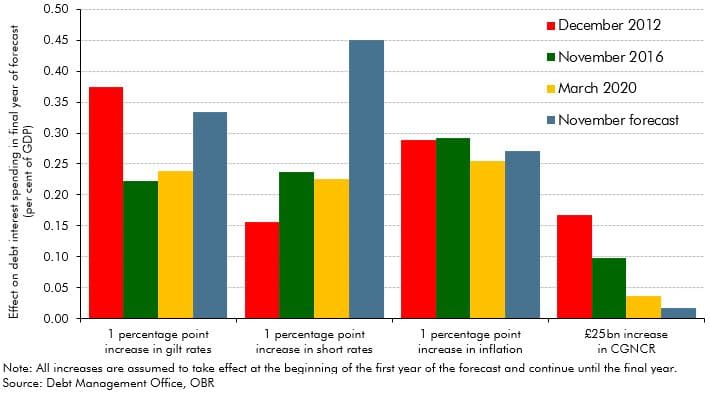

Despite debt rising as a share of GDP to a new post-war peak in our November 2020 forecast, government spending on debt interest was expected to fall to a new historic low as a share of total government revenue. This box explored how this had left the public finances more sensitive to future changes in the cost of servicing this higher debt burden.

On 8 July, the Chancellor announced further measures to support the economy as the lockdown is eased, which we were not notified of in sufficient time to incorporate into our scenarios. This box described the measures included in the package and the costs as estimated by the Treasury.

The Government announced significant increases in departmental expenditure limits for capital spending. In this box we compared previous capital spending plans with outturn and our own capital underspend assumptions.

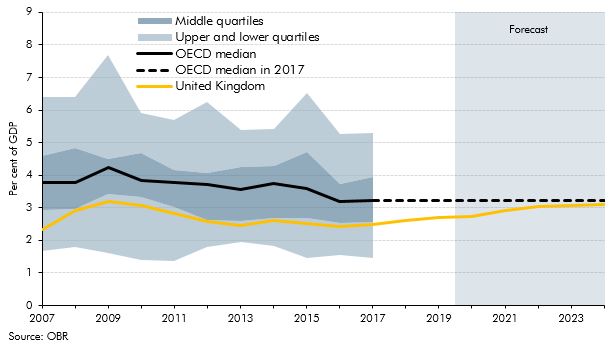

The Government committed to a significant boost to the path of capital spending. This box explored how UK government investment as a share of GDP has compared to other OECD countries and how our March 2020 forecast affects this picture.

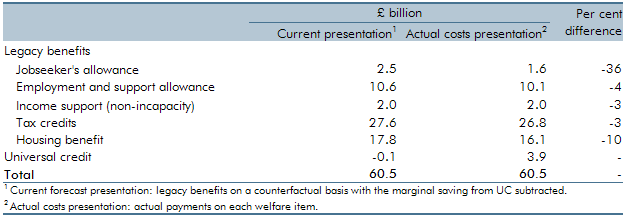

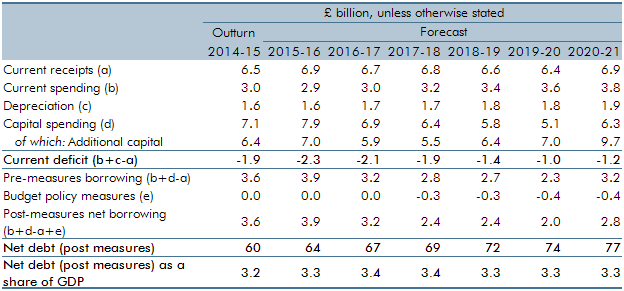

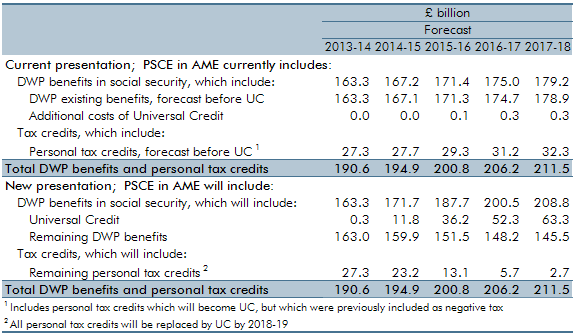

The transition to universal credit (UC) from legacy systems is a key component of our welfare spending forecast, as UC spending will represent 27% of total welfare spending by 2024-25. As detailed in our 2018 Welfare Trends report (WTR), we construct UC spending by forecasting the legacy system as though UC did not exist and then incorporate an estimate of the marginal cost of UC. This allows us to base as much of the forecast on as much administrative data as possible, but it does not directly reflect the real-world change in spending on legacy benefits as spending on UC rises. This approach is unavoidable at present but generates inevitable difficulties for our forecast. This box explored the challenges associated with this approach.

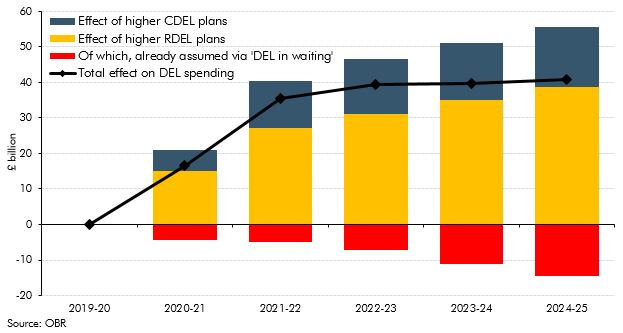

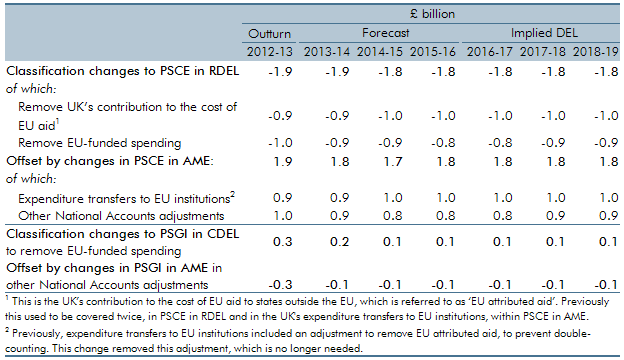

The UK’s exit from the EU presented fiscal savings to the Government in the form of transfers to EU institutions that featured in spending and retained customs duties. We assumed these would be fully recycled into substitute UK spending in previous forecasts. This box explained how we treated these flows as ‘DEL in waiting’ and how this related to the large increases in departmental spending.

In February 2020, the Government announced its intention to introduce a ‘points-based’ migration system from January 2021 that will align migration policy for EU and non-EU migrants. In this box we looked at the effect of the new migration regime on our borrowing forecast.

In June 2019 the BBC announced its decision to begin means-testing eligibility for Free TV licences for those aged 75 and over, based on households containing someone aged 75 or over and also claiming pension credit. This box explores the impact the BBC’s policy could have on pension credit take-up and welfare spending.

In recent years, local authorities have increased their 'prudential' borrowing to take advantage of the low interest rates offered by the Public Loans Work Board. In this box we discussed the example of Spelthorne Borough Council, looking at some of its riskier investments in commercial property and how those may pose a risk to the public finances in the event of an economic downturn.

Where the Government uses off-balance sheet financing to deliver public services this results in a 'fiscal illusion', where the recorded measures of debt and deficit do not reflect economic reality. In this box we looked at the case of housing associations (HAs). These came onto the balance sheet after the Government was given significant controls over them. The Government then legislated just enough to move HAs off-balance sheet. Neither movement made any fundamental change to fiscal sustainability.

By issuing gilts linked to the Retail Prices Index (RPI) the Government exposes itself to inflation risks on interest payments. In this box, we looked at how changes to the formula for calculating RPI would affect our forecast.

Measures of reported disability prevalence are often subject to great variability and this can make drawing precise conclusions from them difficult. In this box, we considered two examples where measures varied. The first related to differences between Labour Force Survey and General Health Survey measures of working-age disability prevalence and the second to large changes in the former. We discussed differences in methodology and changes in attitudes as possible drivers.

Public financial support for disabled people extends beyond the extra-costs disability benefits and includes several other welfare payments. This box gave an overview of some of the most important interactions between disability and other benefits that provide support for disabled people.

Our ability to forecast accurately is heavily dependent on the quality of the data we can use. In this box we explained how statistical and expenditure data could be distorted by problems in delivery of the benefit, and the difficulties this creates in identifying emerging trends in the data.

There are several possible approaches to forecasting benefit spending. In this box we outlined the key issues the modelling of disability benefits needed to address, the three approaches we used to forecast spending, and the strengths and limitations of each, concluding that a combination of approaches was better than reliance on any single one.

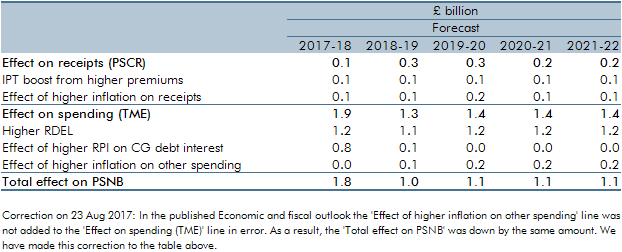

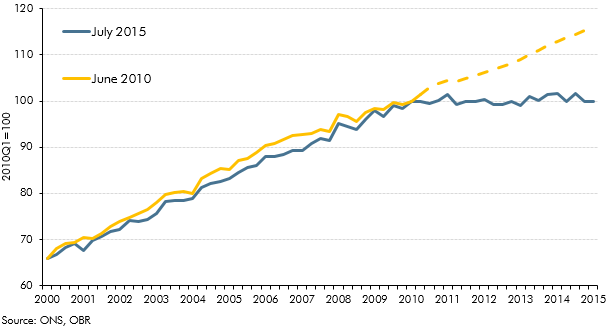

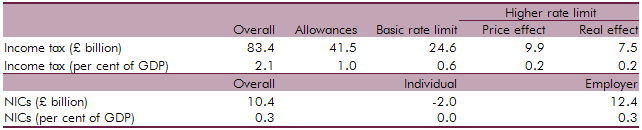

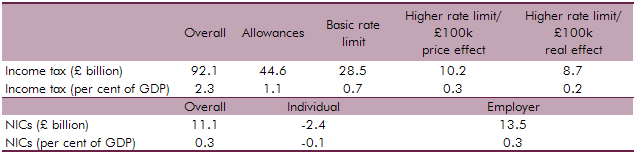

One unforeseen economic development affecting our March 2016 forecast was the upside surprise in inflation in 2017-18 as a result of the fall in the exchange rate. This box described the effect of that surprise on receipts, spending and borrowing.

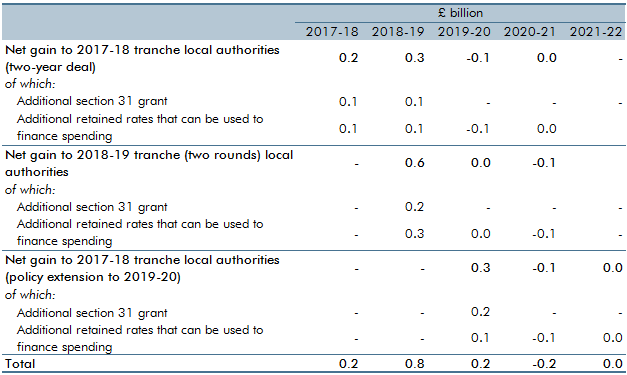

The Government has been piloting full business rates retention since 2017-18. These pilots featured in our forecasts from March 2017. This box reconsidered and re-estimated the fiscal effects of the 100 per cent local retention pilots scheme.

The Government commissioned two reports published in 2017 to inform its review of the State Pension age (SPA): an independent review by John Cridland and a report by the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD). This box summarised the key findings from these two reports.

Our 2018 long-term fiscal projections suggested that, if left unaddressed, the public sector finances would come under increasing pressure over the next 50 years. This box compared our long-term age related spending projections over the period from 2025 to 2065 with those presented in the European Commission's 2018 Ageing Report.

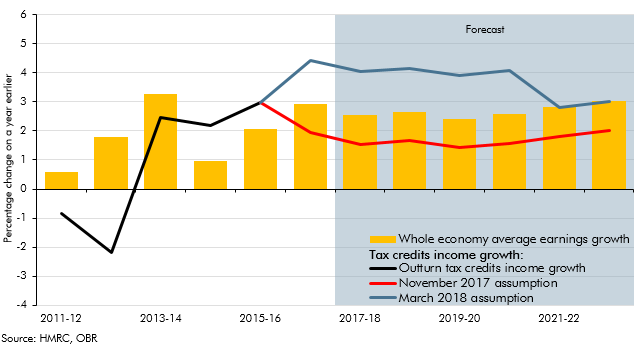

Spending on tax credits came in consistently lower than our forecasts from 2014-15 onwards. In our March 2018 EFO we increased our assumption for the growth in incomes of tax credits families relative to headline earnings growth, significantly lowering our tax spending forecast. This box set out the analysis that underpinned this change in forecasting assumption.

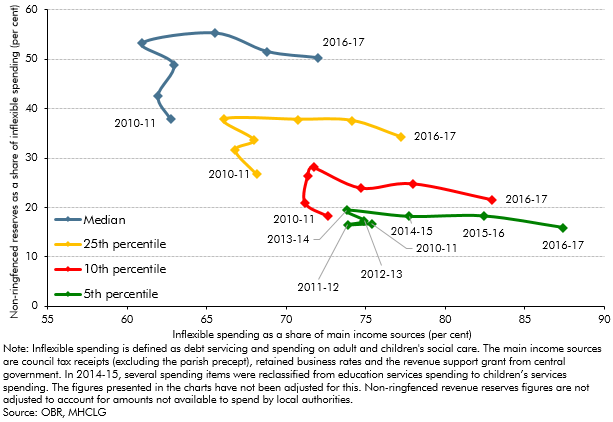

Local authorities’ net use of reserves (the amount they add to or drawdown from their stock of reserves) is a key judgement in our fiscal forecasts. This box from our March 2018 EFO examined two indicators of the general financial health of English local authorities over the period 2010-11 to 2016-17, assessing how these metrics might be used to inform our forecast judgements.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including how the 'work allowances' within it have been changed since the policy was first factored into our forecasts. This box looked at how our estimates of the net cost or saving from UC relative to the legacy benefits have evolved over time, and the important part played by Government decisions to reduce the UC work allowances.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including the role to be played by UC work coaches setting conditions and applying sanctions to encourage claimants to seek and progress in work. This box outlined the role, responsibilities and renumeration of work coaches, as set out in DWP's candidate information pack for applicants for the role.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). PSM is a static micro-simulation model that uses Family Resources Survey (FRS) data to analyse policy changes. This box detailed how the FRS is used in PSM and some of the issues that raises for our UC forecast.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). INFORM is a dynamic micro-simulation model that uses DWP administrative data to forecast the caseloads for different benefits. This box described how INFORM is used in our UC forecast and some of its limitations.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook, economy forecast adjustments included the effects of looser fiscal policy on GDP, the effects of tax policy changes on inflation and the effects of stamp duty relief for first-time-buyers on house prices.

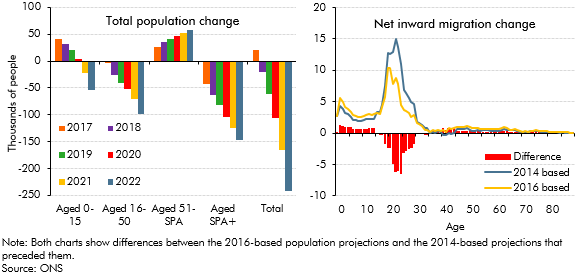

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) published new UK population projections in October 2017, based on 2016 population estimates and updated assumptions for fertility, mortality and net migration. This box compared the latest projections with the previous 2014-based principal projections that underpinned our March 2017 forecast and summarised their effects on our November 2017 fiscal forecast.

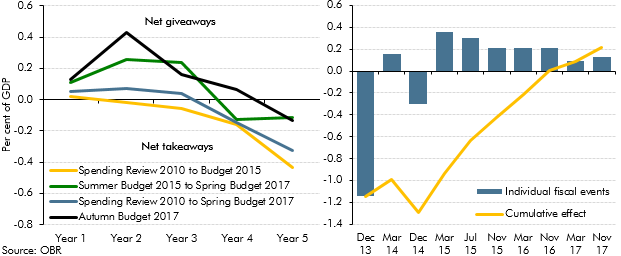

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we incorporate the impact of the policy decisions announced in the Chancellor’s Budget or other fiscal statement (the ‘fiscal event’). This box looked at how measures announced at the previous 16 fiscal events had tended to announce near-term giveaways but with the promise of takeaways in the later years. The Autumn Budget saw this pattern repeated.

Local authorities’ net use of reserves (the amount they add to or drawdown from their stock) is a key judgement in our local authority current spending forecasts as it directly affects borrowing. This box outlined recent trends in use of current reserves, split by English authorities with and without upper-tier responsibilities (such as education and social care), which underpinned our November 2017 forecast judgements.

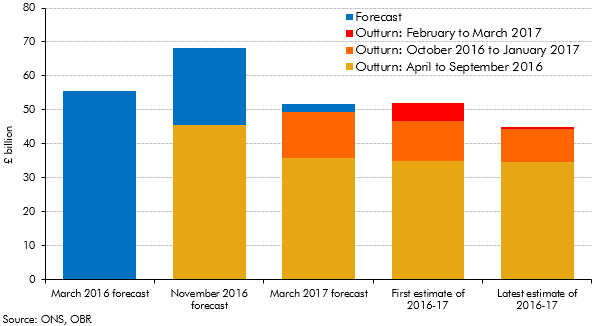

Initial estimates of the deficit can be revised significantly over subsequent months as more reliable data become available. This box set out how our forecasts during 2016 and 2017 evolved and how the outturns for 2016-17 were revised over time.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2017 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we adjusted our economy forecast for the effects of reducing the ‘personal injury discount rate’.

In February 2017, just ahead of the Spring Budget and our March Economic and fiscal outlook, the Ministry of Justice announced that the ‘personal injury discount rate’ would be reduced from 2.5 to minus 0.75 per cent (in inflation-adjusted real terms). This box explained the direct and indirect effects of this change on our receipts and public spending forecasts.

A key issue in our welfare spending forecast is the transition to universal credit (UC) from the existing ‘legacy’ benefits and tax credits systems. In our March 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook, our central forecast was constructed by forecasting the ‘legacy’ system as though UC did not exist, then subtracting from it an estimate of the marginal saving associated with rolling out UC. This box presented estimates for actual gross spending in 2017-18 on UC and the legacy benefits and tax credits that it is replacing.

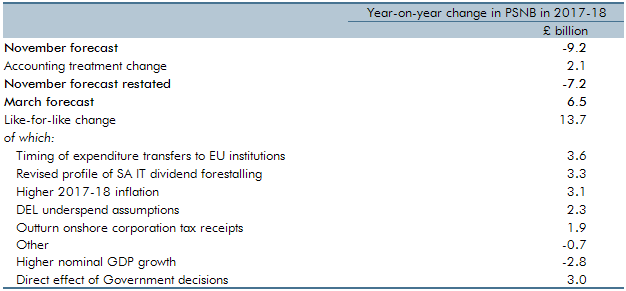

For the first time in any Economic and fiscal outlook, our March 2017 forecast showed post-measures borrowing rising year-on-year in one year of the forecast – 2017-18. This box explored the factors that explained why borrowing was expected to rise in that year, when our November 2016 forecast had assumed it would continue to fall.

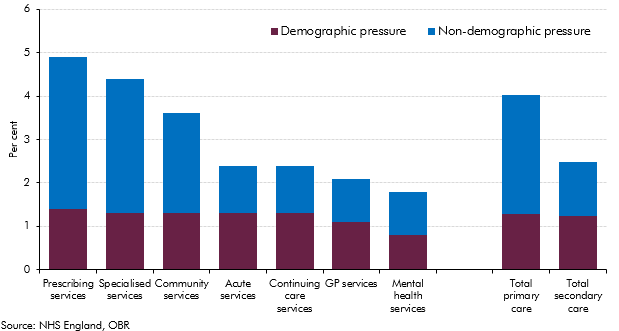

Over the past four decades, health spending in the UK rose faster than GDP (on average in real terms) and it increased steadily in real per capita terms. Demographic change alone could have not explained these rising trends, with other factors expected to provide further upward pressures on health spending. This box summarised the key findings of our WP No. 9 that reviewed the latest evidence on demographic and non-demographic determinants of health spending in the UK and its implications for our long-term health spending projections.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our November 2016 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, economy forecast adjustments included the effects of looser fiscal policy on GDP and the effects of tax policy changes on inflation.

The UK currently makes a substantial net financial contribution to the activities of the European Union. This box outlined the historical liabilities and other commitments entered into that officials, institutions and MEPs were said to be arguing that the UK should pay a share of, in light of Brexit. The box also listed government policy commitments to fund spending in certain areas where EU funding would be withdrawn.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2016 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made a number of economy forecast adjustments to GDP, business investment, wage growth, inflation and the housing market.

In our November 2015 forecast, we anticipated the effect on the public finances of the ONS decision to reclassify private registered providers of social housing in England. This box outlined the policy measures which affect our forecast, the effect on the public finances and changes in these forecasts since November.

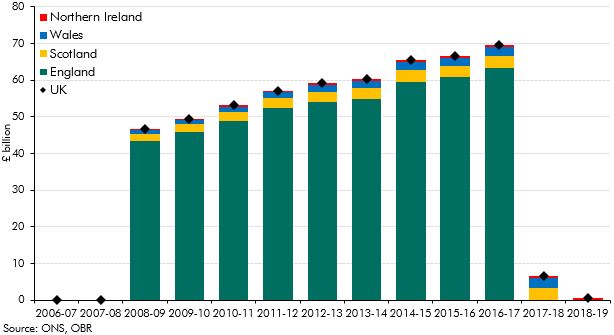

Business rates are a major source of locally-raised finance used to fund locally-administered spending. The Government announced in Autumn Statement 2015 that it would let English local authorities retain 100 per cent of business rates by the end of the Parliament. This box outlined the change in local government financing arrangements and the responsibilities that might be devolved, as well as how these changes would affect our forecast.

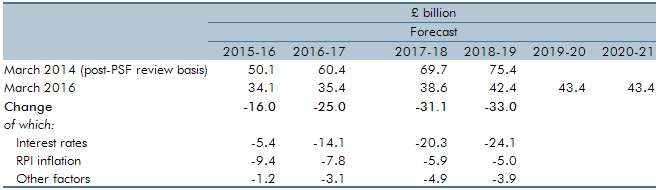

Since our March 2014 Economic and fiscal outlook, our debt interest spending forecast was revised down significantly as market expectations of the interest rates at which the Government can borrow and service its debt moved progressively lower and as inflation fell. This box explained some possible factors that could have caused market expectations of interest rates to rise and the effect on the fiscal position of a sudden increase in interest rates.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In the 2015 Autumn Statement and Spending Review, we made a number of adjustments to real and nominal GDP, the labour market, inflation, and the housing market.

We always try to forecast the public finances consistent with how the ONS will measure them once it has implemented its classification decisions, so that our forecasts will be consistent with that eventual treatment. This box outlined the items included in our November 2015 forecast which the ONS had announced, but had yet to implement.

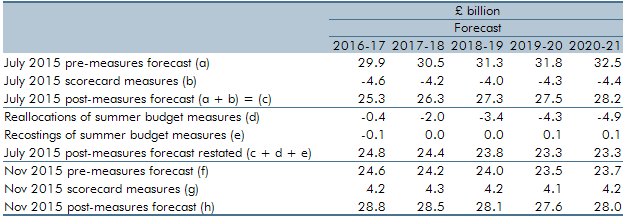

The July 2015 Budget included a large number of complex welfare measures that cut across multiple benefits with many interactions. At Autumn Statement 2015, we identified a number of measures where interaction effects had not been correctly estimated or classified. In this box of our November 2015 EFO, we discussed the re-estimation and reclassification of the interaction effects of a number of welfare measures. This included the reclassification of three tax credits measures and the measure extending the `lone parent obligation’ to ensure that these costings were consistent with our marginal universal credit (UC) forecast. The impact of cuts to tax credits on housing benefit entitlement were also re-estimated and reallocated to the housing benefit forecast from the tax credits forecast as the effect had previously been incorrectly allocated to tax credits.

In the run up to the July 2015 Budget, fiscal policy had been tightened every year since 2010-11. This box, published in our July 2015 Economic and fiscal outlook, set out the fiscal multiplier framework used to estimate the overall effect of changes in fiscal policy on the economy. This box also outlined two ways in which this framework changed with regards to the tapering of multiplier effects across time and the assumed differences in multiplier effects on real and nominal GDP.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In the July 2015 Economic and fiscal outlook, we made a number of adjustments to real and nominal GDP, the labour market, inflation, business and residential investment, and the housing market.

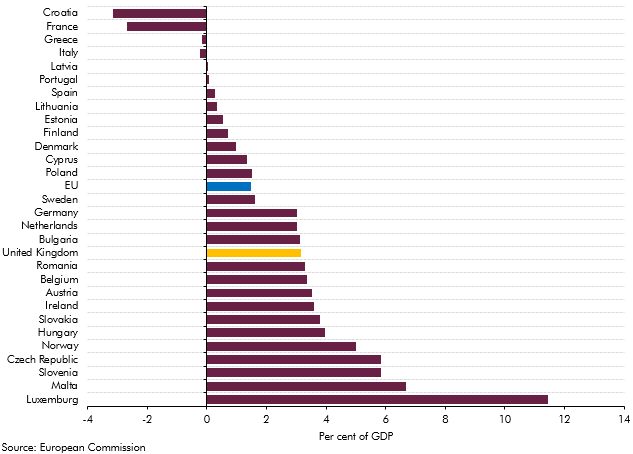

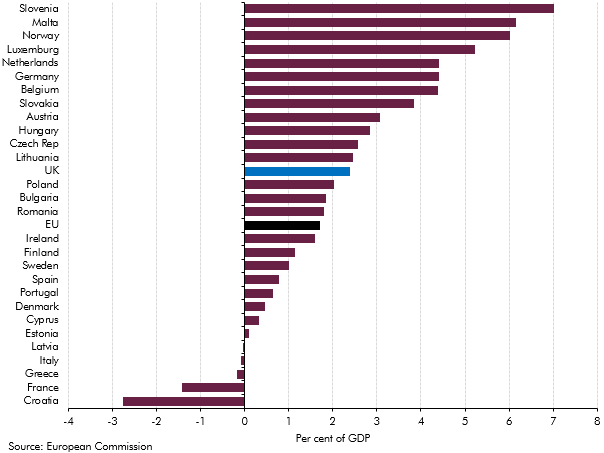

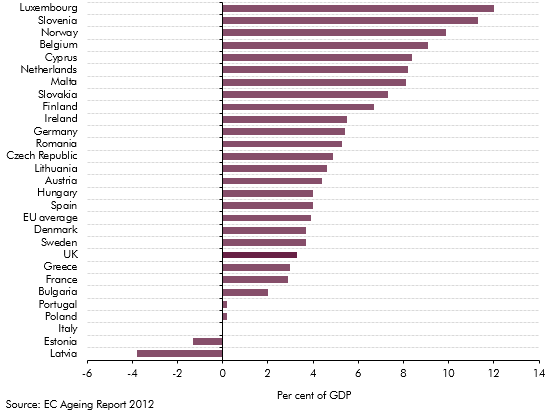

Our 2015 long-term fiscal projections suggested that, if left unaddressed, the public sector finances would have come under increasing pressure over the next 50 years due to rising age-related expenditure. This box compared our long-term age related spending projections with projections from the Ageing Working Group (2015) for the EU countries between 2020 and 2060.

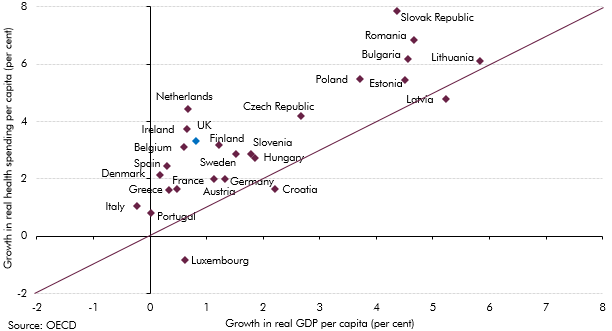

Health spending rose faster than GDP in almost all European countries over the past decade. This box investigated most notable long-term drivers of real spending on health care: demographic effects, income effects and other cost pressures.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2015 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to nominal GDP, inflation and North sea production.

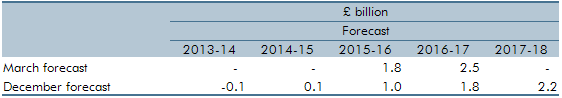

In this forecast, there were two policy switches that shifted spending between RDEL and AME, which applied from 2015-16 onwards. This box outlined these changes and examined the subsequent impact these would have on our forecast.

Our March 2015 Economic and fiscal outlook forecast highlighted large changes in our debt interest forecast since previous fiscal events and the added complexity that debt interest was expressed net of the effect of gilts held by the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility (APF) associated with past quantitative easing. This box described how we produced the debt interest forecast and illustrated some of the sensitivities to which it was subject.

Public finances data are subject to regular classification and methodological changes. This box outlined the classification changes associated with the implementation of the new 2010 European System of Accounts (ESA10). Annex B of our March 2014 EFO explained these changes in more detail.

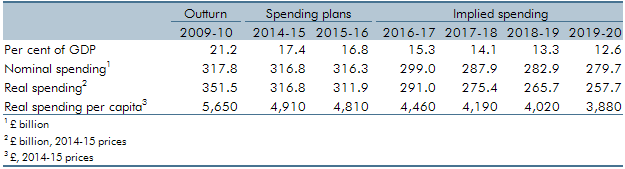

We were asked by our stakeholders whether we considered the implications for current spending on public services (RDEL) in our forecasts to be central, as we are tasked with producing a central forecast. This box outlined RDEL implied spending from 2016-17 to 2019-20 (years in which firm spending plans did not exist and RDEL levels were set by a government policy assumption). The box also examined the implied breakdown of RDEL by some of the main spending areas in 2019-20, in particular examining the implications of then-current government RDEL assumptions for public services spending that was not protected in some way.

In Chapter 4 of our December 2014 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2014-15 to 2018-19. In this box, we discussed revisions we made to the forecast in light of reforms to incapacity and disability benefits. Spending on incapacity benefits was revised up by £0.7 billion a year on average between 2014-15 and 2018-19, largely reflecting a lower-than-expected number of Work Capability Assessments carried out by the Department for Work and Pension’s private contractors. On the basis of the latest evidence, spending on disability benefits was also revised up by £0.7 billion a year on average between 2014-15 and 2018-19. This was largely due to higher than expected success rates for new claims to the personal independence payment.

In Chapter 4 of our December 2014 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2014-15 to 2018-19. In this box, we discussed the latest universal credit rollout plan following the 2014 universal credit business case. Whilst we agreed that the plan to fully rollout universal credit for jobseeker’s allowance cases by March 2016 was central, we decided that the migration plan for claimants of other legacy benefits was still highly uncertain and so implemented a six month delay to the plans for our forecast. This had the effect of reducing the volume of migrations in all years of the forecast but did not substantially alter the universal forecast given that it marginal to the legacy benefits.

This box explored the implications of the new 2010 European System of Accounts (ESA10) on our public finances forecast, ahead of its incorporation in our December 2014 EFO. Annex B of our March 2014 EFO explained these changes in more detail.

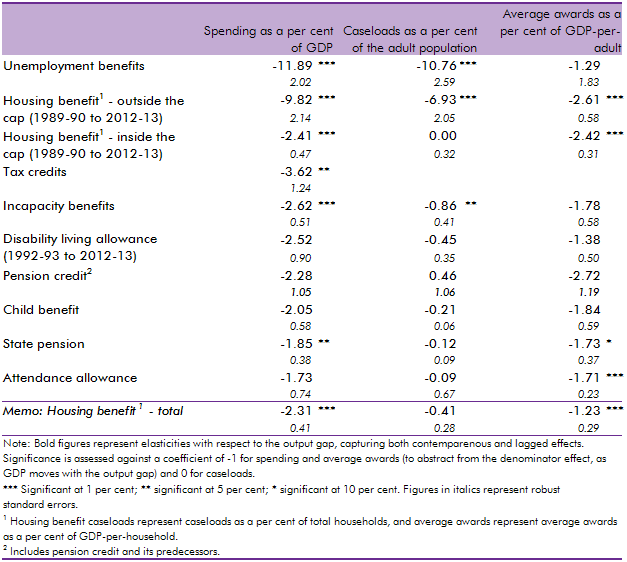

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 reviewed the overall trends in welfare spending. In this box, we considered how responsive welfare spending is to the economic cycle by estimating the elasticity of benefits and tax credits spending as a share of GDP with respect to changes in the output gap (the difference between actual GDP and an estimate of its potential or underlying level). We found that the most counter-cyclical benefits have caseloads closely associated with the economic cycle whereas mildly counter-cyclical benefits are likely to only exhibit cyclicality due to spending varying less than GDP, thereby producing a denominator effect.

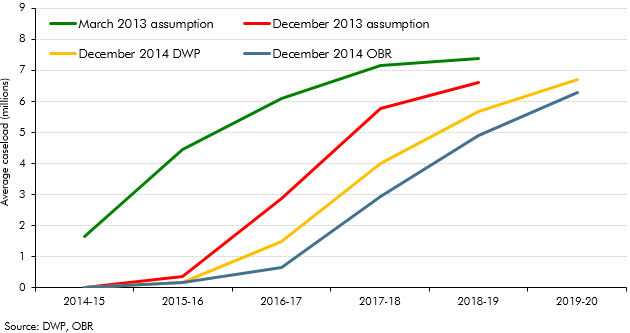

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 reviewed the overall trends in welfare spending. In this box we discussed the latest Universal Credit (UC) forecast at the time of writing. This forecast assumed UC would roll-out slowly during 2014-15 and 2015-16 before accelerating in 2016-17 and 2017-18, by which time 5.8 million people were expected to be receiving the benefit. We highlighted that the roll out of UC had already been subject to previous delays and that the decision to produce a top-down UC forecast helped mitigate the uncertainties caused by delivery challenges. We then decomposed the marginal UC forecast into its constituent gross savings and gross costs forecasts.

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 8 considered spending on unemployed people. This box compared outturn data on unemployment and claimants of unemployment benefits to the levels implied by our March 2014 forecast. As the economy performed better than anticipated in our March 2014 forecast, the ratio of claimants of unemployed benefits to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) measure of unemployment deviated from our projections. This was largely due to a drop in the rate of inflows into unemployment benefits and a rise in the rate of outflows from unemployment benefits, though an increase in the number of people looking for jobs but not claiming unemployment benefits may have increased LFS unemployment and so been a contributing factor.

The European System of National and Regional Accounts (ESA 10) changed the arrangements for funded defined benefit pension schemes. The new approach required that the net liabilities of these schemes for the future costs incurred from past activities were calculated using commercial accounting concepts. This box provided a summary of the effects that the new treatment would have, as well as its relevance to the Whole of Government Accounts (WGA).

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our December 2013 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we adjusted our inflation forecast to reflect changes in fuel duty.

In this forecast, we switched to using spending data from a new source, which was the Treasury’s new public spending database known as OSCAR (short for their ‘Online System for Central Accounting and Reporting’). This led to some switches between DEL and AME, which we treated as classification changes, because they affected our presentation of DEL and AME for all years, including outturn and forecasts. This box explained those changes.

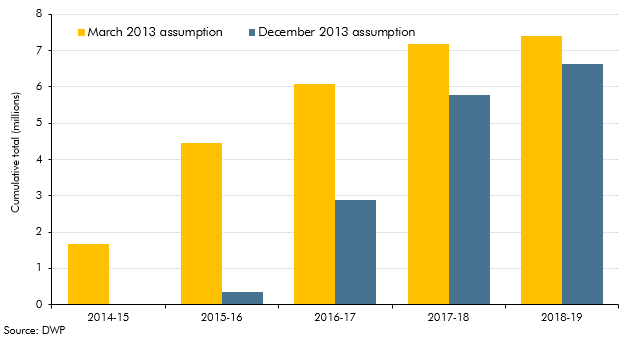

In Chapter 4 of our December 2013 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2013-14 to 2017-18. In this box, we discussed the delays to the Government’s universal credit rollout plan. Compared to the March 2013 rollout plan, large increases in the universal credit caseload were assumed to start later than previously planned in 2016 and 2017. Fewer people were also expected to be on universal credit at the end of the forecast horizon, with 700,000 fewer claimants assumed to have migrated by the end of 2017-18 compared to the March 2013 rollout plan. We explained that the changes to the rollout schedule was a key source of change in the profile of our forecast relative to March 2013, with lower spending up to 2015-16.

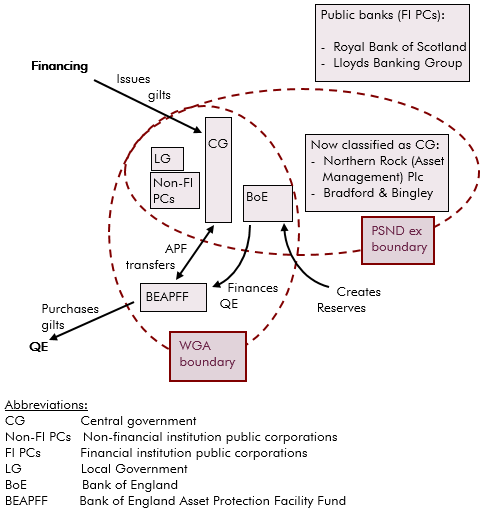

In 2013 the National Accounts measure of PSNB and PSND widened to include Bradford and Bingley and Northern Rock (Asset Management), and also included the APF transfers from the BEAPFF to central government. This box explained how the QE and APF transactions are treated in WGA and in the National Accounts, and the differences between them.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2013 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to our forecasts of real GDP, business investment and inflation

In Chapter 4 of our March 2013 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2013-14 to 2017-18. In this box, we introduced a new marginal cost presentation of the universal credit forecast and also outlined contributing factors to changes in the forecast. These factors included policies announced at the 2012 Autumn Statement and changes to a number of the universal credit policy parameters as well as refinements to the methodology and assumptions used to forecast universal credit. The analysis in this box has since been superseded by developments in the universal credit forecast.

The Whole of Government Accounts (WGA) contains information on future fiscal liabilities that are relevant for our forecast. This box explained how we ensured that those future liabilities reported in the WGA were fully reflected in our forecasts, where those liabilities were expected to affect the public finances.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our December 2012 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to our forecasts of real GDP, inflation and property transactions

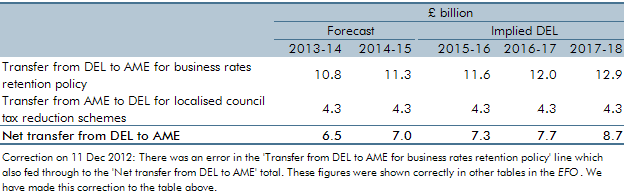

In this forecast there were two policy switches that shifted spending between RDEL and AME, which applied from 2013-14 onwards. These policies were for the 50 per cent retention of business rates for local authorities in England, and for localised council tax reduction schemes. This box outlined these changes and examined the subsequent impact these would have on our forecasts.

In Chapter 4 of our December 2012 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2012-13 to 2016-17. In this box, we discussed changes to the provisional universal credit forecast that was included in our March 2012 EFO. Changes to the forecast were due to a number of factors, including policies announced at Budget 2012 and finalisation of policy parameters in universal credit as well as .refinements to the methodology and assumptions used to forecast universal credit. We also discussed the main uncertainties in the forecast, which largely related to the unpredictability given the scale of the policy. The analysis in this box has since been superseded by developments in the universal credit forecast, though many of the key uncertainties remain.

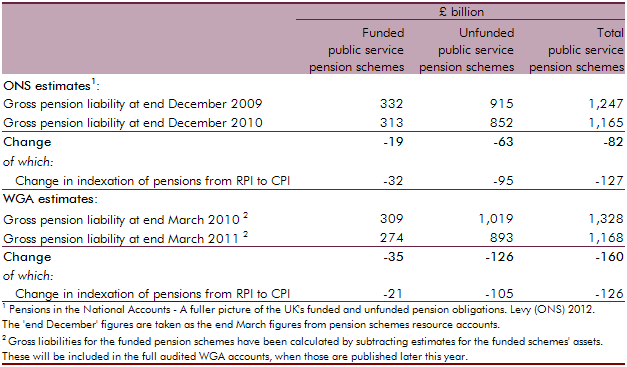

In April 2012, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published the first set of new statistics on the total gross liabilities of UK pension providers, including the UK government. This box explored how the ONS’ pension liability estimates were calculated for public service pensions and state pensions, and compared the public service estimate to the Whole of Government Accounts (WGA) methodology.

The European Commission (EC) produces its own analysis of ageing pressures for member states every three years. This box contrasted the forecast made by the EC and the OBR for UK age related spending such as pensions, health care and long-term care.

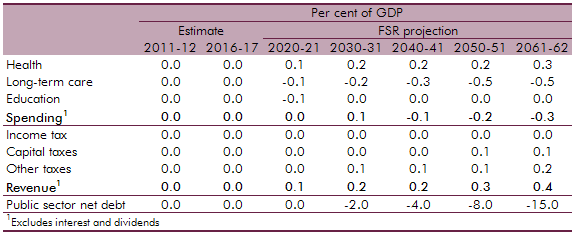

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) produce generational accounts estimates for the UK. The OBR produces its own long-term projections by using profiles that break down spending by year of age. This box compared the differences in public finance forecasts between the OBR and the NIESR with the latter implying a lower level of net debt by 2061‑62.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our March 2012 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to our forecasts of real GDP, business investment and inflation.

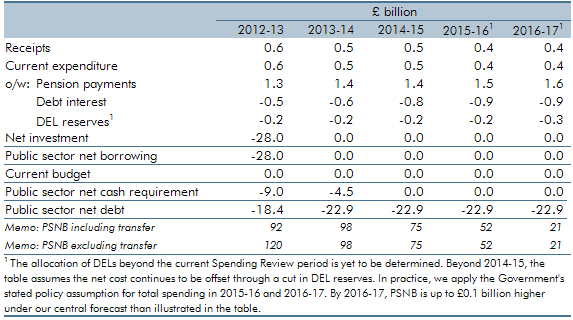

The Government announced that it intends to take on Royal Mail’s historic pension deficit with effect from April 2012. This box explored how the transfer of the relevant assets and liabilities will impact the public sector finances.

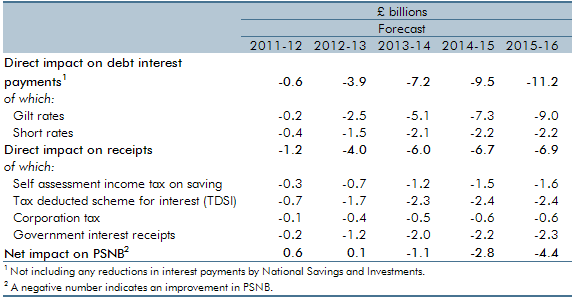

This box set out the impact of changes in interest rates on our public finances forecast, including debt interest spending and income tax receipts. Updated versions of our ready reckoners can be found on our website.

The Government announced in June 2011 that it intended to take on Royal Mail’s historic pension deficit with effect from April 2012. This box explored the provisional estimates of the impact this transfer had on the public finances.

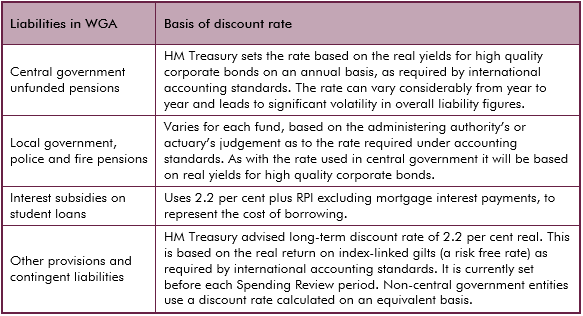

Discount rates are used to convert future cash flows into an equivalent one-off upfront sum or present value, allowing them to be presented alongside stock measures on a single balance sheet. But there is no single ‘correct’ discount rate and the use of discount rates presents some challenges in analysis of balance sheet movements over time. This box from our first Fiscal sustainability report in 2011 outlined the different discount rates used in the Treasury’s Whole of Government Accounts.

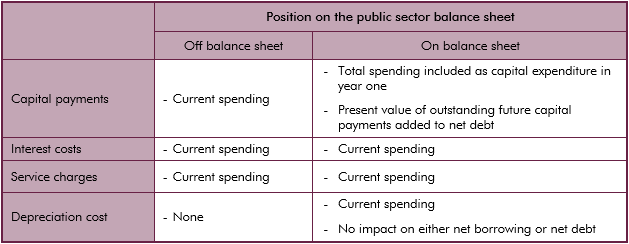

Depending on ONS classification assets relating to PFI contracts can be on the public sector or the private sector balance sheet. This box outlined the accounting of PFI contracts in the National Accounts and WGA.

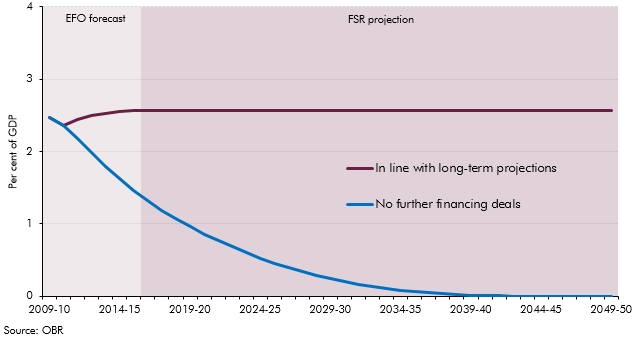

The majority of Private Finance Initiative (PFI) assets are held off the public sector balance sheet in the National Accounts. The running costs relating to existing PFI contracts are included within agreed departmental spending envelopes. This box explored the impact on our net debt projections if all capital liabilities relating to PFI contracts were included.

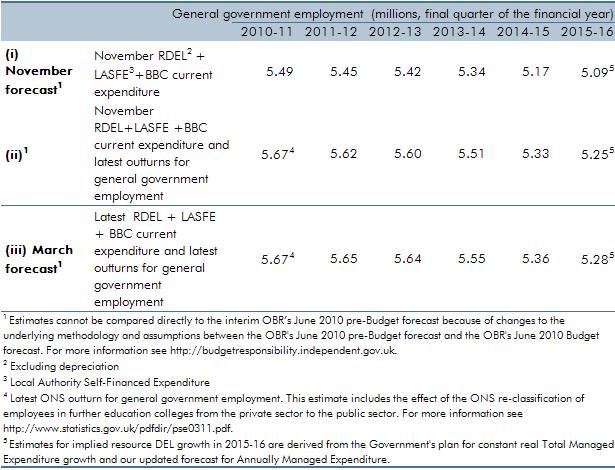

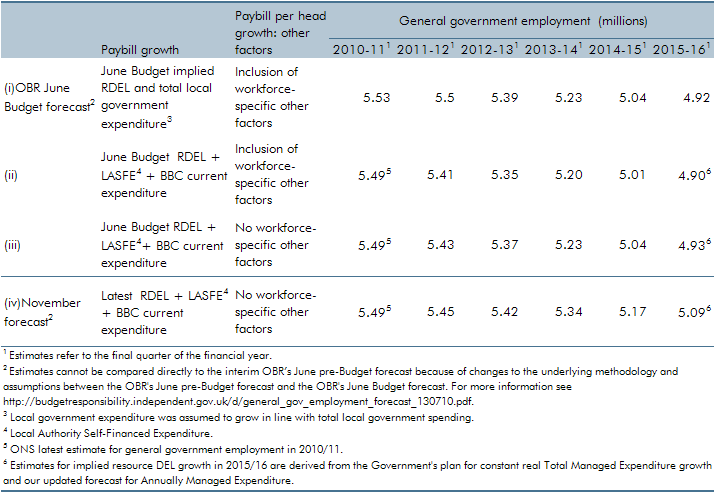

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. Ahead of our March 2011 forecast, ONS estimates of general government employment were revised up, largely reflecting the reclassification of employees in further education colleges. In this box we set out the extent to which changes to our general government employment forecast were a result of our revised projections for paybill growth as opposed to data revisions.

This box set out the various impacts that higher inflation has on the public finances. These include direct effects (e.g. on income tax and debt interest spending), the impact on nominal tax bases (such as household consumption) and the impact on departmental spending.

The OBR provides independent scrutiny of policy costings and determines any resultant impact on the economic forecast. An estimate of the impact of a policy measure is included in the public finances forecast only when a firm policy has been announced and there is sufficient detail to quantify the effect of the policy. This box summarised the policies that were included in our November 2010 forecast.

Our general government employment (GGE) forecast is based on projections of the growth of the total government paybill and paybill per head, which is in turn based on the Government's latest spending plans. Ahead of our November 2010 forecast, those plans were updated as part of the 2010 Spending Review. We also made a number of refinements to our forecasting approach. In this box we described revisions to our general government employment forecast and explain the extent to which these changes were the result of methodological changes as opposed to revised spending plans.