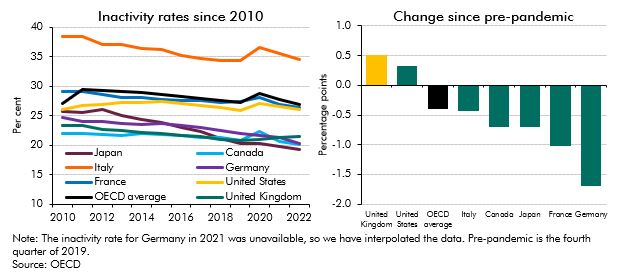

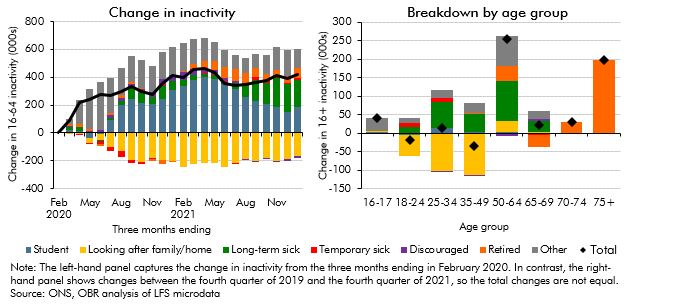

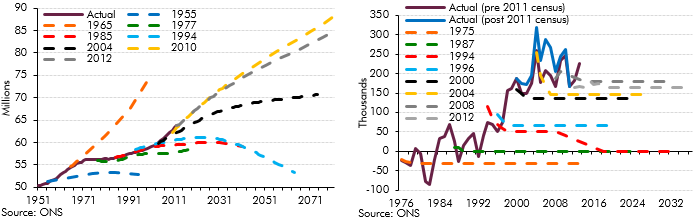

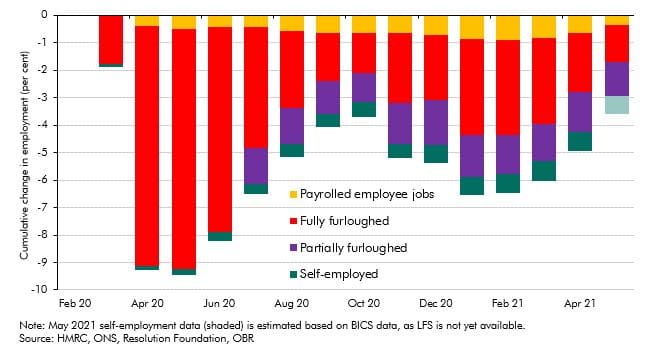

Our labour market forecast includes projections of labour market indicators in relation to the population aged 16 and over – i.e. all adults. Some headline labour market indicators published by the ONS are presented in relation to the population aged between 16 and 64. This is intended to capture working-age adults, notwithstanding changes to the state pension age. Employment and inactivity rates are most commonly presented on this basis, for example.

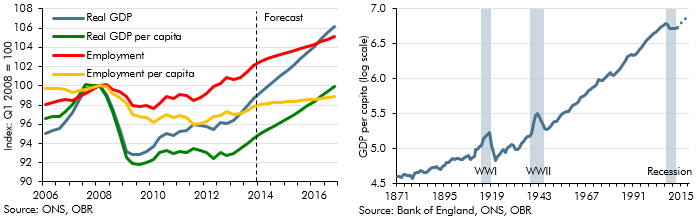

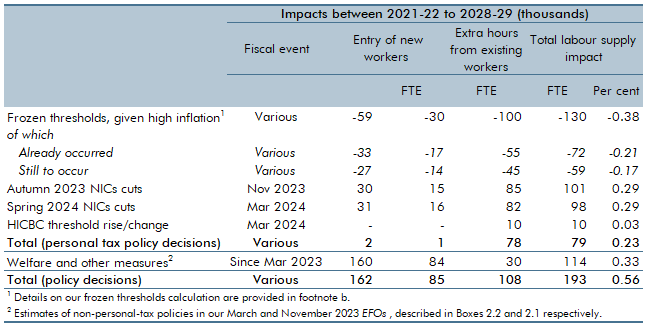

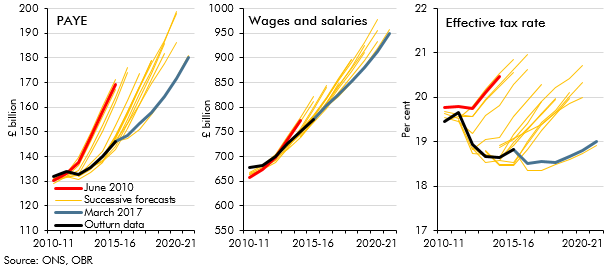

The indicators that we forecast include participation (and how it is split between employment and unemployment) and average weekly hours worked. Employment growth is an important driver of wages and salaries growth, which in turn drives the biggest sources of tax receipts: income tax and national insurance contributions.

We used to forecast the ‘claimant count’ measure of unemployment, but due to the distorting effects of the rollout of universal credit, the ONS no longer considers it a ‘National Statistic’. We have also stopped forecasting it, although we continue to produce forecasts of the caseloads of relevant benefits as part of our welfare expenditure forecast.

We produce a forecast for the potential growth rates of these headline labour market indicators in order to construct our potential output forecast. Once the output gap is closed, GDP is typically assumed to grow broadly in line with potential output over the remainder of the forecast period, and similarly the labour market variables are expected to move in line with our forecast for their underlying trends.

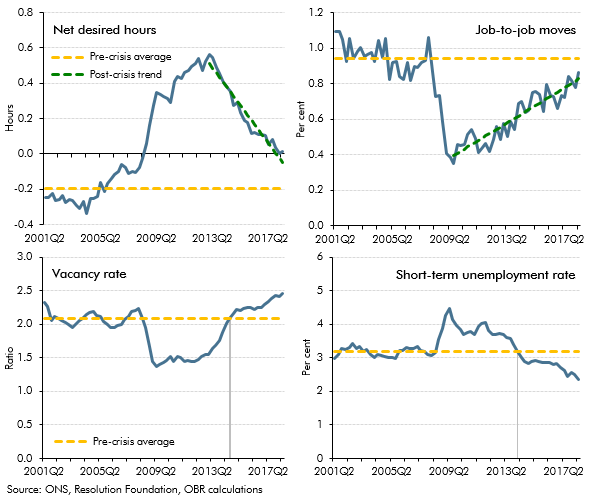

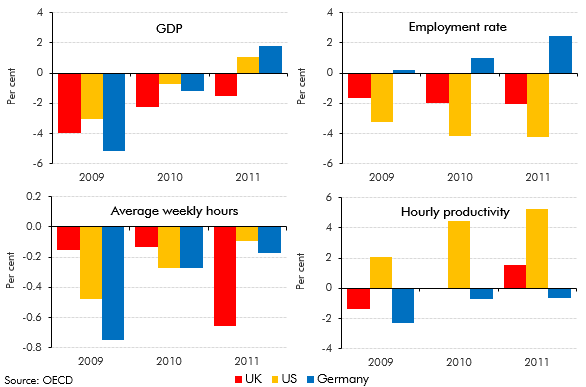

In the early part of the forecast, when output is typically assumed to be away from its potential level, we decompose the output gap into component gaps relating to the unemployment and participation rates, average hours, and productivity. We consider this approach of estimating an overall output gap then decomposing it – rather than estimating component gaps and summing them to the total – to be the best use of the available information on the cyclical position of the economy, some of which relates to the overall output gap (e.g. inflation or wage growth) and some to the component gaps (e.g. capacity utilisation or recruitment difficulties).

As with the overall output gap, each of the individual component gaps represents the difference between the actual level of that component and its trend level. Our forecasts for the actual levels of each variable are produced by considering both the profile of the gaps and of the actual values, iterating as necessary until the BRC is comfortable that each element of the forecast is central.

We use several approaches to decompose the output gap, all involving a degree of judgement. These approaches can and do vary between forecasts. Beyond the short term, it is generally assumed that these variables gradually return to their underlying trend levels, with judgements about how the output cycle interacts with the labour market determining the speed at which each variable does so.