Our forecasts of income and expenditure allow us to produce a forecast of sector net lending – the balance of saving and capital spending for each sector. This provides a useful diagnostic on the coherence of the economy forecast. We also construct a forecast of the household balance sheet – the stock of households’ financial assets and liabilities – that is consistent with our forecast of households’ net lending.

Net lending and balance sheets

This Forecast in-depth page has been updated with information available at the time of the March 2024 Economic and fiscal outlook.

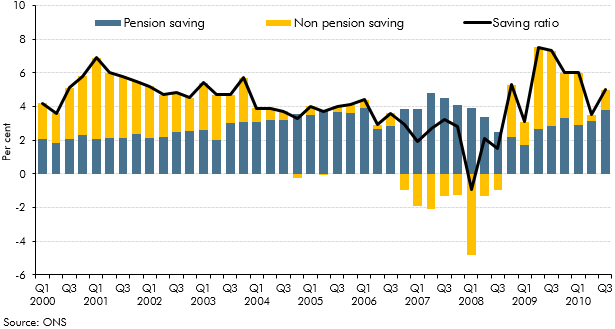

Household saving ratio

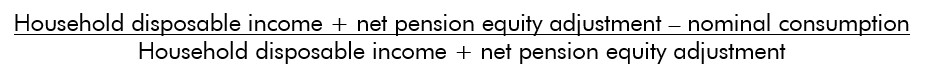

The household saving ratio forecast is defined in the National Accounts as being equal to:

Our forecasts for nominal household consumption and household disposable income are described in the relevant sections of this guide.

The net pension equity adjustment represents the amount added to or subtracted from the net equity held by households in funded pension schemes. It is equal to contributions to funded pension schemes by employers (both imputed and actual) and employees, less pension benefits paid out. Employers’ pension contributions are generally assumed to grow in line with wages and salaries, plus any adjustment for the effect of policies, including auto-enrolment. Our forecast for employee pension contributions is largely determined by the gilt rate and closing pension liabilities, consistent with the measurement of this variable in the National Accounts. Again, we will make any adjustment necessary for the effect of policies, including auto-enrolment. Payments of pension benefits are generally assumed to grow in line with the size of the relevant age group of the population, plus inflation.

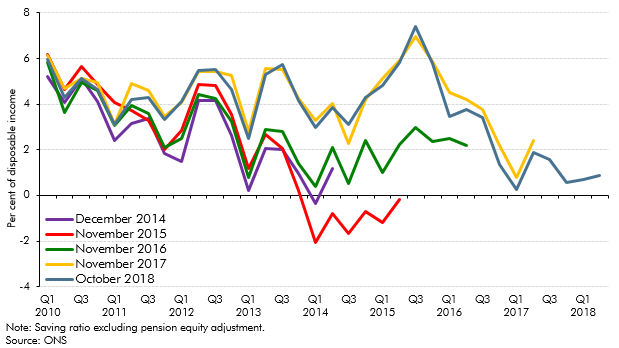

While the household saving ratio forecast is mechanically derived from the forecasts of its individual components, it provides a useful diagnostic on the household income and spending forecasts as a whole. The resulting profile of the saving ratio can therefore be used to inform our judgements about household consumption and household disposable income. In doing so we typically also consider a measure of the saving ratio that excludes the pension equity adjustment from the numerator and denominator, on the basis that this component may be less visible to households (especially the imputed elements) and therefore perhaps less relevant to their consumption decisions.

Once we have a forecast for household saving, we can then derive a forecast for household net lending by taking household saving (which is equal to the numerator of the saving ratio) and subtracting household gross capital formation (which is made up largely of nominal household investment, and is determined by our forecasts for real residential investment, house prices and the consumption deflator).

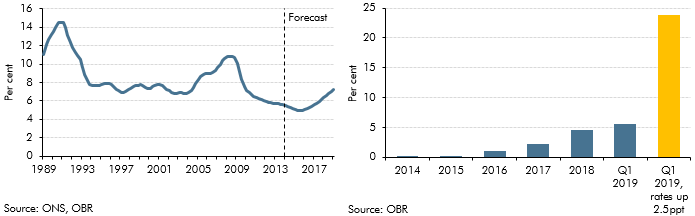

During the Covid pandemic in 2020, the household saving ratio rose to a record high, as consumer spending fell sharply due to public health restrictions, while incomes were supported by government policy. The saving ratio has subsequently fallen back, but remains elevated compared to pre-pandemic averages. We expect households to keep their saving high in the short term, both as a precaution against shocks and due to high interest rates. Our forecast for the saving ratio then returns towards longer-run averages in the medium term.

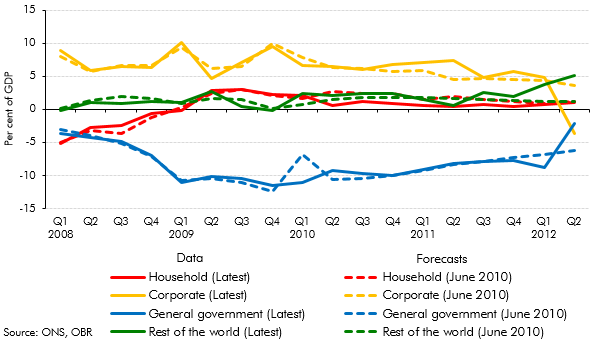

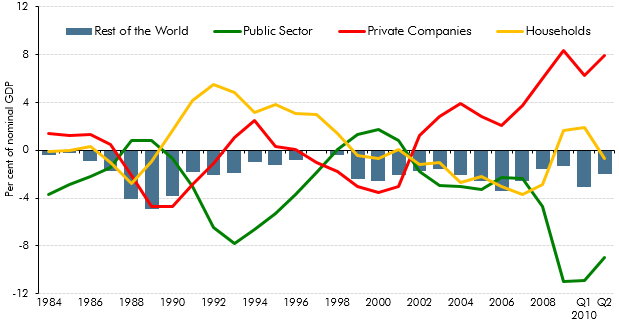

Sector net lending

In the National Accounts framework underpinning our economy forecast, the income and expenditure of the different sectors imply a path for each sector’s net lending or borrowing from others. In principle, these sum to zero – for each pound borrowed, there must be a pound lent. In practice, ONS estimates of sector net lending do not sum precisely to zero, reflecting differences between the income and expenditure measures of GDP (the ‘statistical discrepancy’). Our standard practice is to assume that this difference remains broadly flat over the forecast period.

Once we have determined our forecasts for expenditure and income for each sector, this gives a forecast for net lending. Taking each sector in turn:

- Households’ net lending position reflects household saving and household investment.

- The rest of world sector’s net lending position is largely determined by the current account.

- The public sector net lending position is taken directly from our forecast of the public finances.

- The corporate sector net lending position reflects corporate profits and investment. It is derived by residual in our forecast to ensure that the sector net lending positions sum to zero across the economy as a whole. This is consistent with the ONS treatment of this sector in the National Accounts: corporate profits, for example, are often subject to ‘alignment’ adjustments to bring the income measure of GDP into line with the headline estimate. But it is important to note that even though the net lending position of the corporate sector is derived by residual, it is consistent with our forecast for corporate profits and corporate expenditure (such as business investment) as these elements are components of aggregate expenditure and aggregate income.

While our sectoral net lending forecasts are the arithmetic consequence of judgements and assumptions elsewhere in the forecast, they do not necessarily mark the end of the forecast process. The profile of each sector’s net lending provides an important overall diagnostic on the coherence of the economic forecast. This can prompt adjustments to the judgements we make about each sector’s income and expenditure in subsequent rounds of the forecast.

During 2020, there were very large movements in sectors’ net lending positions as a result of the pandemic and the huge fiscal support provided in response. Net borrowing by the Government increased significantly, offset by the household and corporate sectors. As the effects of the pandemic have receded, sectors’ net lending positions have moved back towards pre-pandemic positions.

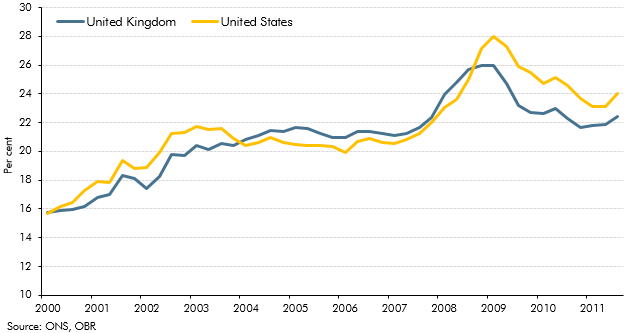

Household balance sheet

The flow of funds constraint

Our forecast of the household sector balance sheet includes forecasts of assets and liabilities. The balance sheet forecast is ‘stock-flow consistent’: that is, households’ acquisition of assets and liabilities are consistent with their aggregate flows of income and saving. The change in the stock of assets or liabilities then reflects both households’ net acquisition of the relevant asset or liability and, where relevant, revaluation effects.

The household balance sheet is subject to the flow-of-funds constraint as set out in the National Accounts:

![]()

Our forecast for household net lending is the starting point for forecasting for the household balance sheet. The assets forecast is split into four elements: deposits, equity, pensions and insurance, and ‘other’ assets. The liabilities forecast is split into secured (i.e., mortgage) debt and unsecured debt. Our forecast starts by first establishing a baseline forecast for each of these elements. To ensure consistency between the stock and flow position of households’ financial accounts, any ‘residual’ between the net lending implied by the flows of saving and the net lending implied by our baseline forecast of the ‘stocks’ is apportioned across the components of the household balance sheet. These adjustments ensure that the household balance sheet forecast is consistent with the net lending path implied by our forecasts of income and expenditure. The following sections set out how we produce our baseline forecast for each element of the household balance sheet.

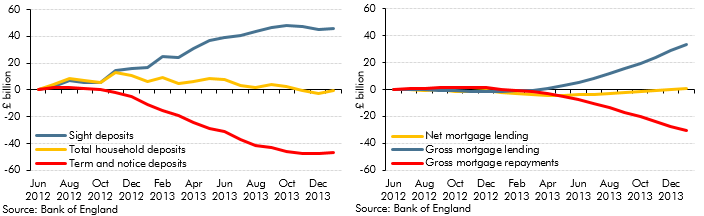

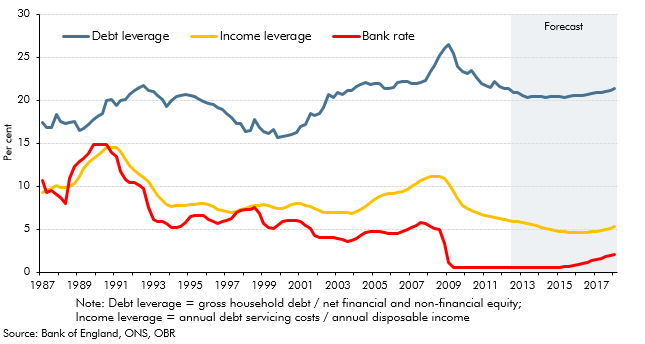

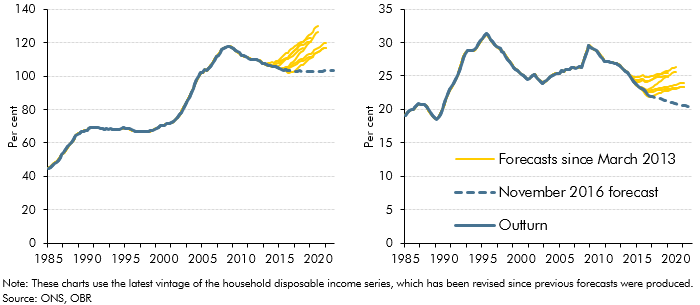

Household liabilities

- Our forecast for secured (mortgage) debt is based on an assumed path for borrowing for house purchases, less net repayments and write-offs. Borrowing for house purchases is projected using our forecasts for house prices, property transactions and an assumption about the loan-to-overall-value ratio. (This is a whole economy equivalent of the familiar loan-to-value ratio in individual house purchases.) Net repayments and write-offs are projected using historical trends. Further details of this methodology can be found in Box 3.3 of our November 2016 Economic and fiscal outlook.

- The accumulation of unsecured debt is projected based on its relationship with several other variables in the forecast, including consumption, unemployment and property transactions. The forecast also includes an assumption about write-offs, which are assumed to remain at a constant proportion of the stock.

Household assets

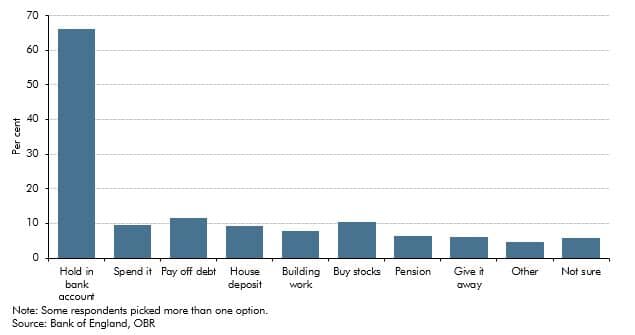

- Our forecast for household deposits is informed by a number of factors, such as the outlook for household consumption and interest rates.

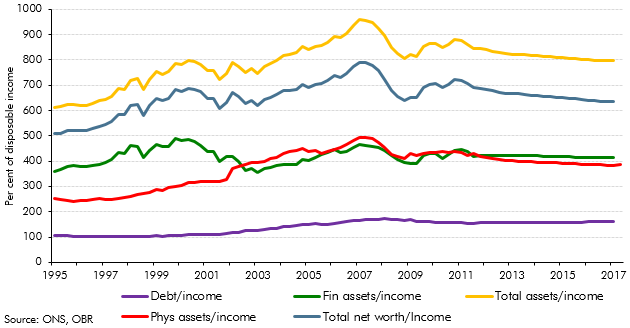

- Changes in the value of households’ stock of equity assets will reflect both households’ acquisition of equities and revaluations as equity prices fluctuate. The net acquisition of equity assets is projected in line with households’ net lending position. Revaluation effects are based on our forecasts for domestic and world equity prices.

- Our forecast for the stock of pension and insurance assets is determined by the accumulation of those assets and by revaluation effects. The accumulation of pension assets reflects our forecast for the net flow of pension saving, taken from the net pension equity adjustment in the household saving ratio. The accumulation of insurance assets is forecast using past trends and the rate of insurance premium tax. Revaluation effects are calculated using our forecast for domestic and world equity prices, and long-term interest rates, which are used to discount part of the stock.

- Our forecast of ‘other’ assets, such as households’ debt securities, is informed by recent trends as well as the outlook for nominal GDP growth.

Household net worth

The difference between the value of households’ financial assets and liabilities gives a value for their financial net worth. Household net worth is equal to financial net worth plus the value of households’ physical assets (i.e., housing). Our forecast for the latter is derived from our forecasts of the housing stock and house prices.

Boxes

Within each of our key publications we include topical ‘boxes’. These self-contained analyses are unique to this publication and tend to cover recent developments in the economy or public finances that complement the main discussion of our analyses.