Box sets » Welfare spending » Universal credit

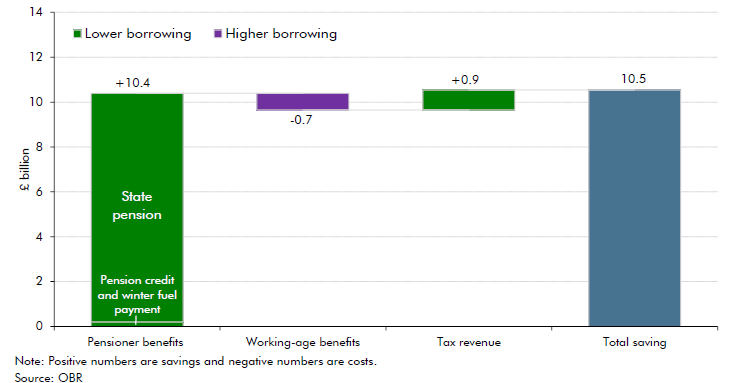

As life expectancy has increased, successive governments have increased the state pension age, and it next increases between 2026 and 2028 from 66 to 67. In this box, we estimated the impact of this increase on pensioner welfare spending, working-age welfare spending, and tax revenue.

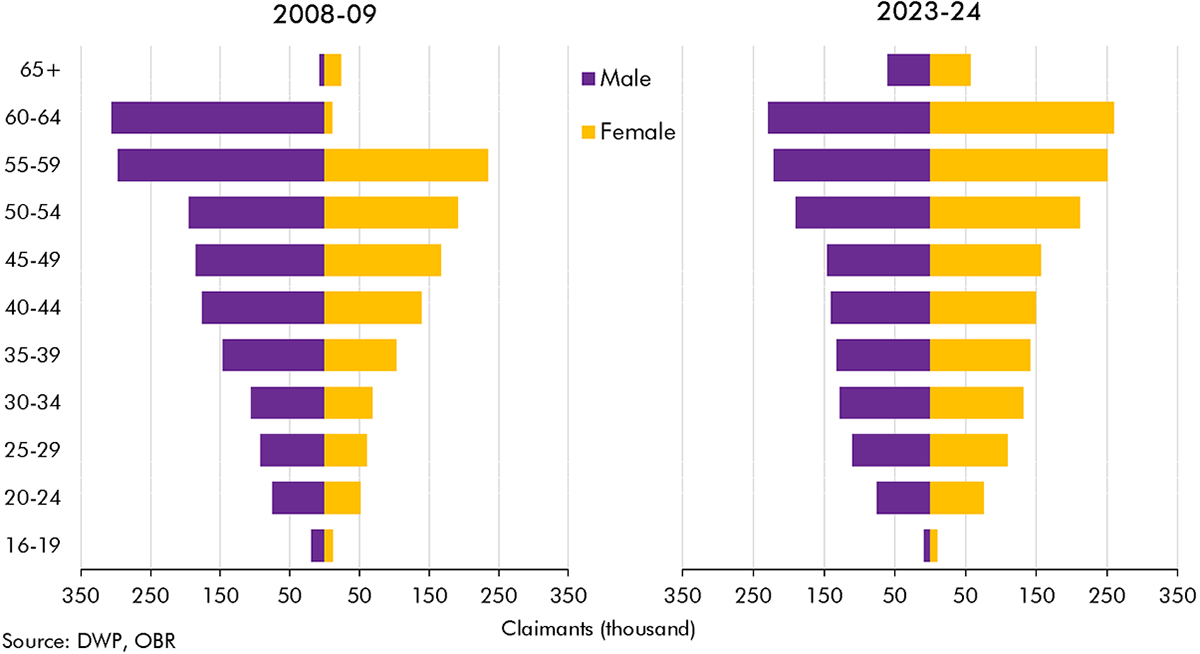

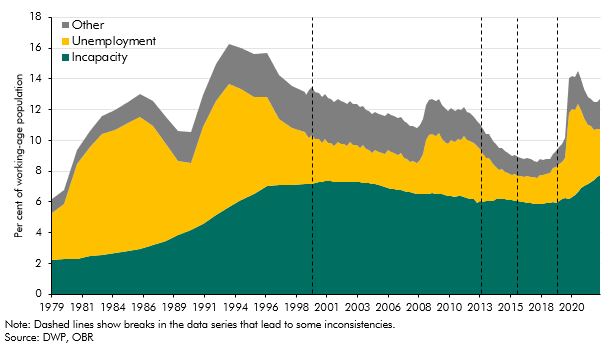

The rise in incapacity benefits after 2013-14 coincided with a rise in the state pension age. In this box we explained how much of the change in incapacity benefit caseload was explained by rises in the state pension age and the ageing of the population.

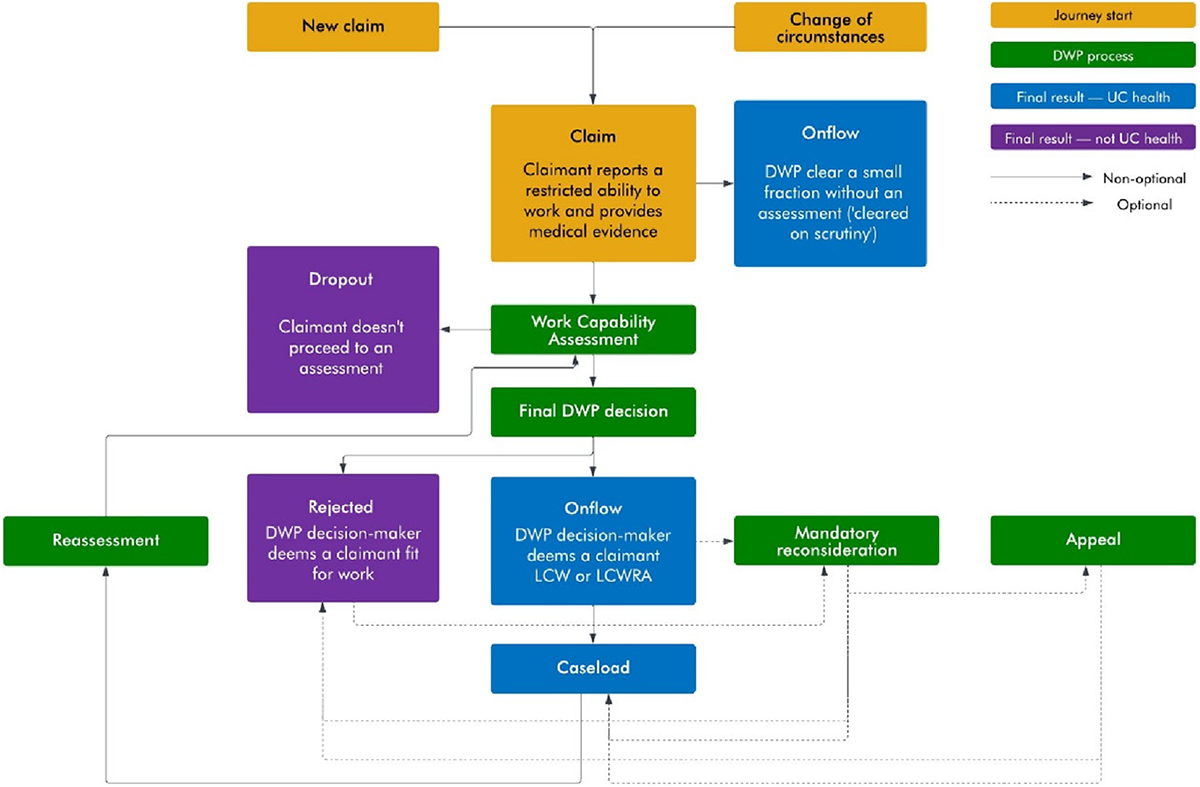

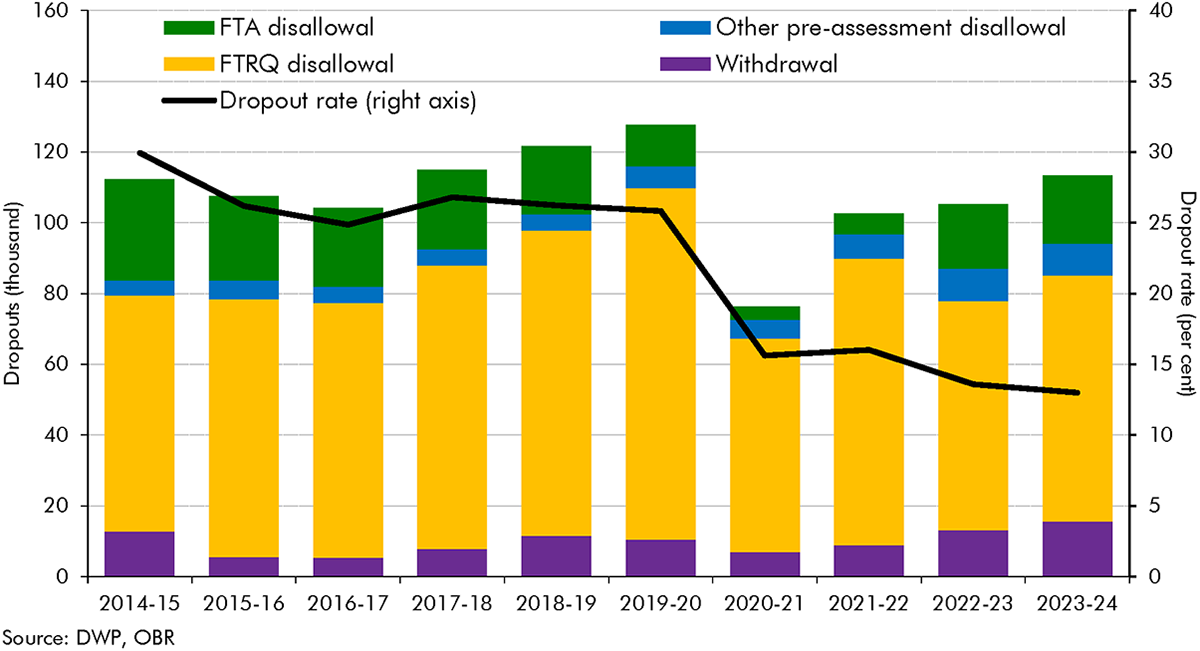

There are several stages before a claimant joins an incapacity benefit. In this box we explained the stages involved in joining either the less-severe (LCW) or more-severe (LCWRA) groups under universal credit, and differences in the predecessor employment support and allowance benefit.

Both incapacity and disability benefit onflows have grown substantially since 2018-19. In this box we compared the different drivers of these respective increases in onflows and drew some lessons from the granular disability benefit data for how incapacity onflows may have been changing.

Benefits for working-age claimants with health problems have changed significantly over the last thirty years through the introduction of new benefits and assessments. This box described how the UK welfare system operates for working age claimants with and without health problems, and how this has changed over time.

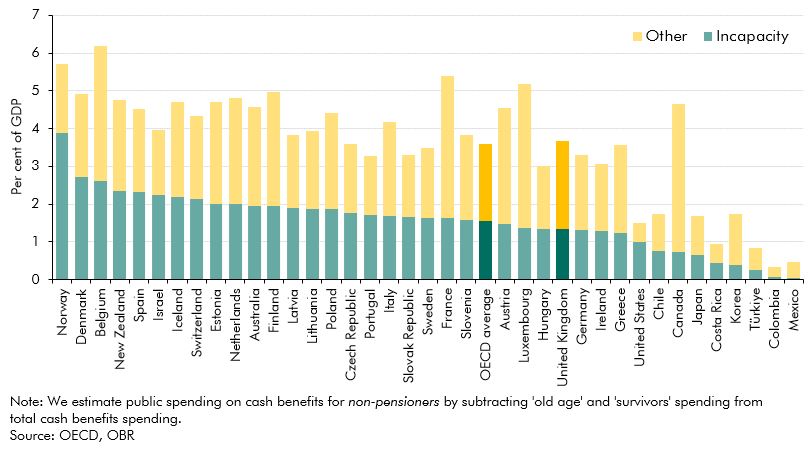

The UK spent close to the OECD average on non-pensioner cash benefits in 2019. This box compared the provision and generosity of health-related welfare across countries, drawing on several international studies.

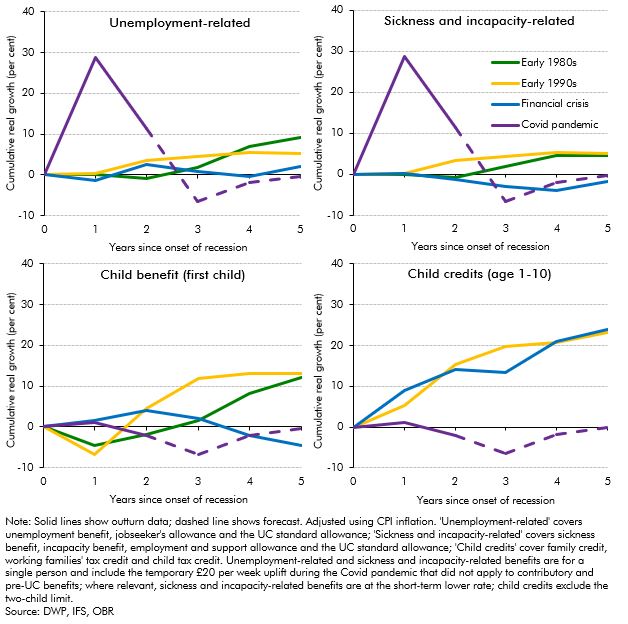

The real-terms value of benefits was forecast to fall by around 5 per cent in 2022-23 (£12 billion in total) before catching up the year after, largely due to the significant rise in inflation and the lag in benefit uprating. In this box we compared these post-pandemic uprating dynamics to the real value of non-pensioner benefit rates following the previous three recessions. This showed that the forecast trough in the real value of benefits was deeper in the wake of the pandemic than for any of the previous three recessions.

On 8 July, the Chancellor announced further measures to support the economy as the lockdown is eased, which we were not notified of in sufficient time to incorporate into our scenarios. This box described the measures included in the package and the costs as estimated by the Treasury.

The transition to universal credit (UC) from legacy systems is a key component of our welfare spending forecast, as UC spending will represent 27% of total welfare spending by 2024-25. As detailed in our 2018 Welfare Trends report (WTR), we construct UC spending by forecasting the legacy system as though UC did not exist and then incorporate an estimate of the marginal cost of UC. This allows us to base as much of the forecast on as much administrative data as possible, but it does not directly reflect the real-world change in spending on legacy benefits as spending on UC rises. This approach is unavoidable at present but generates inevitable difficulties for our forecast. This box explored the challenges associated with this approach.

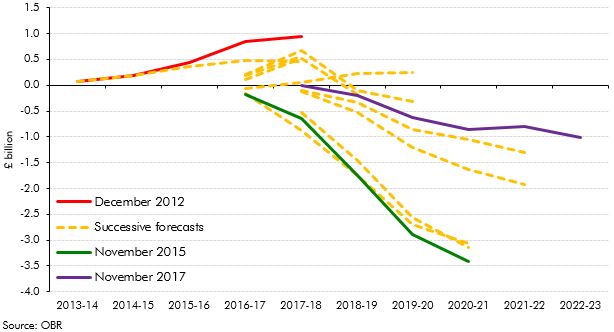

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including how the 'work allowances' within it have been changed since the policy was first factored into our forecasts. This box looked at how our estimates of the net cost or saving from UC relative to the legacy benefits have evolved over time, and the important part played by Government decisions to reduce the UC work allowances.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 3 looked at the design of universal credit, including the role to be played by UC work coaches setting conditions and applying sanctions to encourage claimants to seek and progress in work. This box outlined the role, responsibilities and renumeration of work coaches, as set out in DWP's candidate information pack for applicants for the role.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). PSM is a static micro-simulation model that uses Family Resources Survey (FRS) data to analyse policy changes. This box detailed how the FRS is used in PSM and some of the issues that raises for our UC forecast.

In our 2018 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 described how we model the effects of universal credit on spending. This draws heavily on two models owned and operated by DWP - the Policy simulation model (PSM) and the Integrated forecasting model (INFORM). INFORM is a dynamic micro-simulation model that uses DWP administrative data to forecast the caseloads for different benefits. This box described how INFORM is used in our UC forecast and some of its limitations.

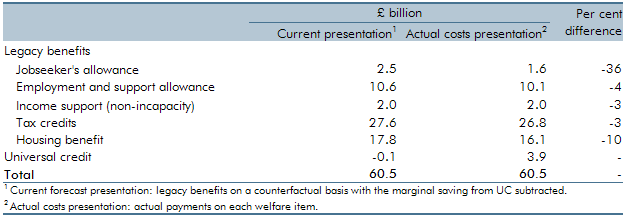

A key issue in our welfare spending forecast is the transition to universal credit (UC) from the existing ‘legacy’ benefits and tax credits systems. In our March 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook, our central forecast was constructed by forecasting the ‘legacy’ system as though UC did not exist, then subtracting from it an estimate of the marginal saving associated with rolling out UC. This box presented estimates for actual gross spending in 2017-18 on UC and the legacy benefits and tax credits that it is replacing.

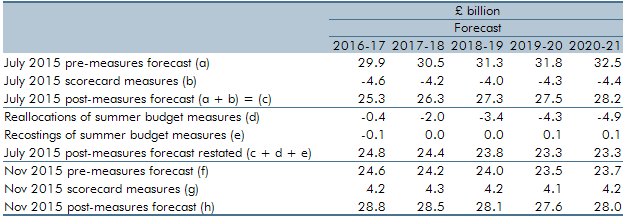

The July 2015 Budget included a large number of complex welfare measures that cut across multiple benefits with many interactions. At Autumn Statement 2015, we identified a number of measures where interaction effects had not been correctly estimated or classified. In this box of our November 2015 EFO, we discussed the re-estimation and reclassification of the interaction effects of a number of welfare measures. This included the reclassification of three tax credits measures and the measure extending the `lone parent obligation’ to ensure that these costings were consistent with our marginal universal credit (UC) forecast. The impact of cuts to tax credits on housing benefit entitlement were also re-estimated and reallocated to the housing benefit forecast from the tax credits forecast as the effect had previously been incorrectly allocated to tax credits.

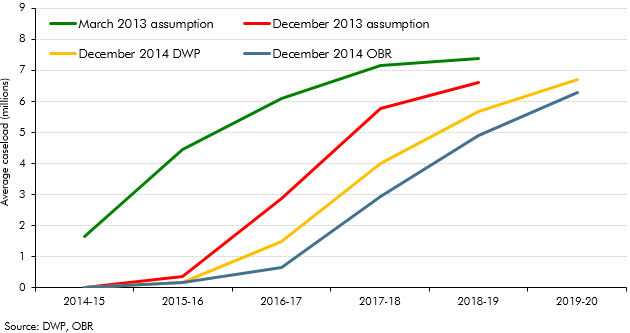

In Chapter 4 of our December 2014 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2014-15 to 2018-19. In this box, we discussed the latest universal credit rollout plan following the 2014 universal credit business case. Whilst we agreed that the plan to fully rollout universal credit for jobseeker’s allowance cases by March 2016 was central, we decided that the migration plan for claimants of other legacy benefits was still highly uncertain and so implemented a six month delay to the plans for our forecast. This had the effect of reducing the volume of migrations in all years of the forecast but did not substantially alter the universal forecast given that it marginal to the legacy benefits.

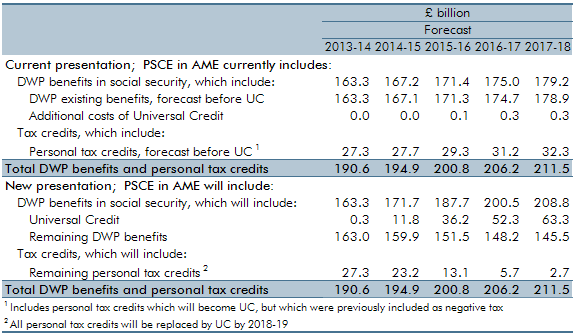

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 4 reviewed the overall trends in welfare spending. In this box we discussed the latest Universal Credit (UC) forecast at the time of writing. This forecast assumed UC would roll-out slowly during 2014-15 and 2015-16 before accelerating in 2016-17 and 2017-18, by which time 5.8 million people were expected to be receiving the benefit. We highlighted that the roll out of UC had already been subject to previous delays and that the decision to produce a top-down UC forecast helped mitigate the uncertainties caused by delivery challenges. We then decomposed the marginal UC forecast into its constituent gross savings and gross costs forecasts.

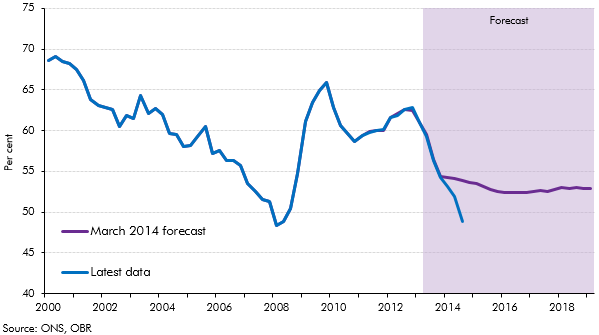

In our 2014 Welfare trends report, Chapter 8 considered spending on unemployed people. This box compared outturn data on unemployment and claimants of unemployment benefits to the levels implied by our March 2014 forecast. As the economy performed better than anticipated in our March 2014 forecast, the ratio of claimants of unemployed benefits to the Labour Force Survey (LFS) measure of unemployment deviated from our projections. This was largely due to a drop in the rate of inflows into unemployment benefits and a rise in the rate of outflows from unemployment benefits, though an increase in the number of people looking for jobs but not claiming unemployment benefits may have increased LFS unemployment and so been a contributing factor.

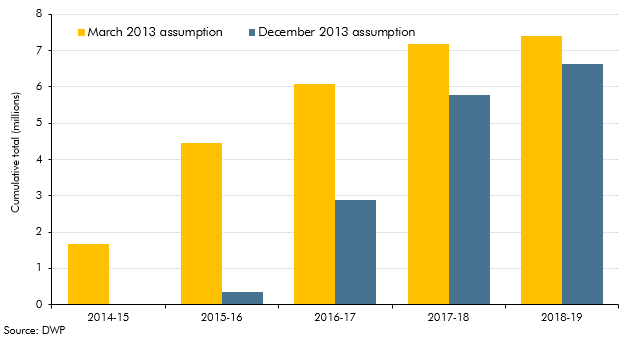

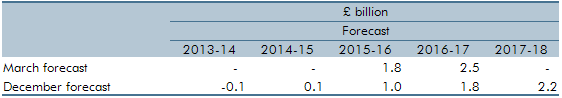

In Chapter 4 of our December 2013 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2013-14 to 2017-18. In this box, we discussed the delays to the Government’s universal credit rollout plan. Compared to the March 2013 rollout plan, large increases in the universal credit caseload were assumed to start later than previously planned in 2016 and 2017. Fewer people were also expected to be on universal credit at the end of the forecast horizon, with 700,000 fewer claimants assumed to have migrated by the end of 2017-18 compared to the March 2013 rollout plan. We explained that the changes to the rollout schedule was a key source of change in the profile of our forecast relative to March 2013, with lower spending up to 2015-16.

In Chapter 4 of our March 2013 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2013-14 to 2017-18. In this box, we introduced a new marginal cost presentation of the universal credit forecast and also outlined contributing factors to changes in the forecast. These factors included policies announced at the 2012 Autumn Statement and changes to a number of the universal credit policy parameters as well as refinements to the methodology and assumptions used to forecast universal credit. The analysis in this box has since been superseded by developments in the universal credit forecast.

In Chapter 4 of our December 2012 EFO, we discussed the fiscal outlook for 2012-13 to 2016-17. In this box, we discussed changes to the provisional universal credit forecast that was included in our March 2012 EFO. Changes to the forecast were due to a number of factors, including policies announced at Budget 2012 and finalisation of policy parameters in universal credit as well as .refinements to the methodology and assumptions used to forecast universal credit. We also discussed the main uncertainties in the forecast, which largely related to the unpredictability given the scale of the policy. The analysis in this box has since been superseded by developments in the universal credit forecast, though many of the key uncertainties remain.