Box sets » Net lending and balance sheets

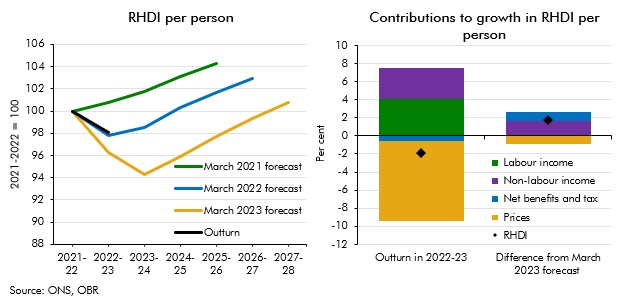

Real household disposable income turned out stronger than our recent forecasts expected for 2022-23. This box explained that differences are largely explained by net benefits and taxes as well as non-labour incomes providing stronger support to living standards than forecast.

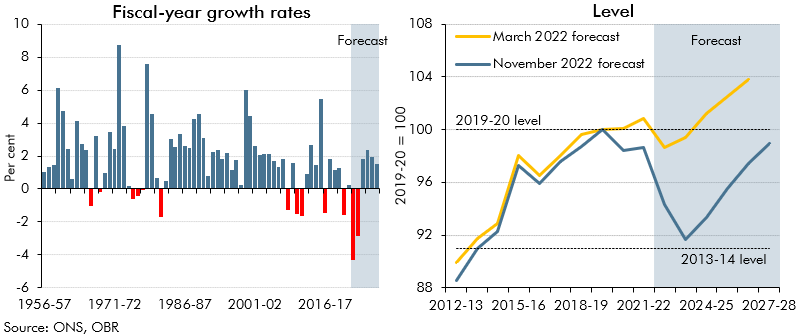

In 2022-23 and 2023-24, living standards are set for the largest fall on record. This box set out our forecast for real household income, the impact of government policy in buffering the income shock, and its implications for our consumption forecast.

This box explored how the pandemic and associated policy response changed the flow of funds between the different sectors of the UK economy. It then considered the implications of how those flows unwind for the pace and sustainability of the recovery.

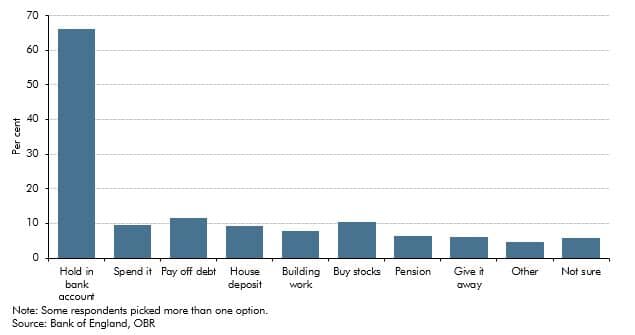

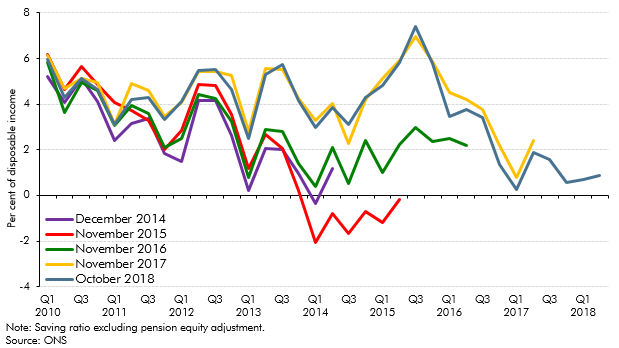

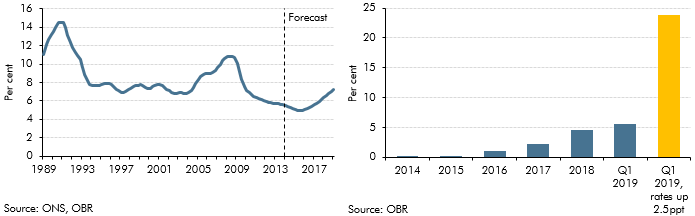

In our October 2018 forecast, the saving ratio – excluding pension contributions - was expected to turn negative, while unsecured debt was expected to rise steadily as a share of household income. In this box, we set out why this did not mean our growth forecast was dependent on a large and unsustainable increase in consumption, nor a significant expansion in consumer credit. Estimates of the saving ratio are subject to frequent revision, while only just over a third of unsecured debt relates to consumer credit, with a small and growing share made up by student loan debt. We also expect total interest payments on debt to remain subdued over the forecast period.

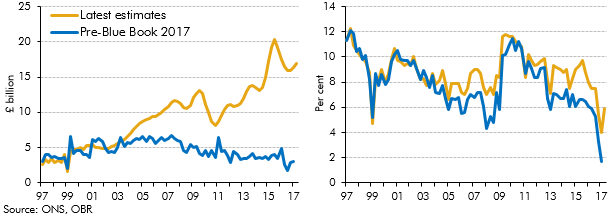

In recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of people setting themselves up as single-director companies (‘incorporations’), implying an increase in the share of household income received as dividends. ONS estimates of households dividend income were revised significantly as part of Blue Book 2017, and better capture this rise in incorporations. This box discussed the implications of these revisions, which implied a much higher level of household disposable income and household saving than previous estimates.

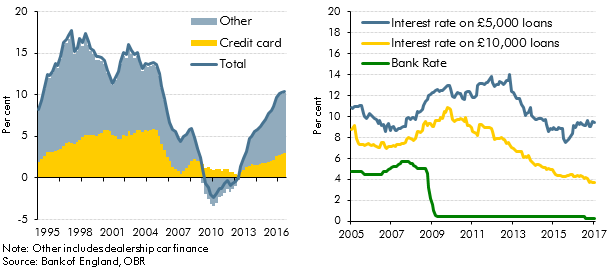

Strong growth in consumer credit in the run-up to our March 2017 Economic and fiscal outlook had prompted concerns among some commentators about its sustainability. In this box we considered the drivers of consumer credit growth, including the role of dealership car finance, and the extent to which it may have supported household consumption growth.

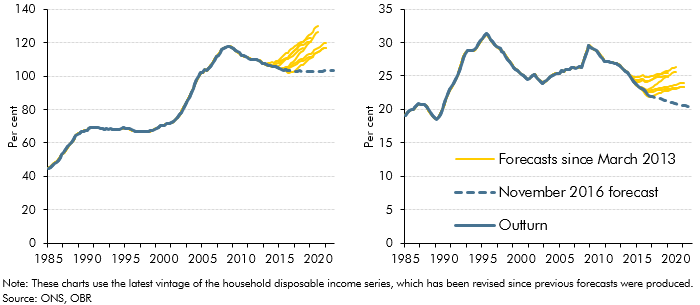

Before November 2016, our forecasts for mortgage debt (secured debt) were based on forecasts for mortgage demand and supply, as the determined by relationships in our house price model. In light of systematic forecast errors, this box outlined changes to our methodology for forecasting mortgage debt, which moved to an approach based on an accumulation identity.

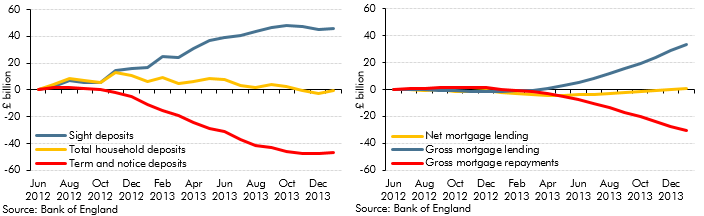

In 2013, households’ balances in ‘time deposit’ accounts (savings with fixed maturity) fell by £36 billion. This box outlined possible reasons for this by exploring the wider household savings behaviour. The cumulative change in annual deposit flows showed rapid increases in 'sight deposits'. This was possibly explained by narrowing spreads between 'time' and 'sight' deposit interest rates or normalisation of household investment behaviour. Changes in annual mortgage flows also suggested that revival of housing market activity could have been responsible for switching between deposit types. The ability of households to shift very large deposit balances over relatively short timeframes was one reason why the impact of savings and pensions measures discussed in Box 3.3 of the same EFO was subject to considerable uncertainty.

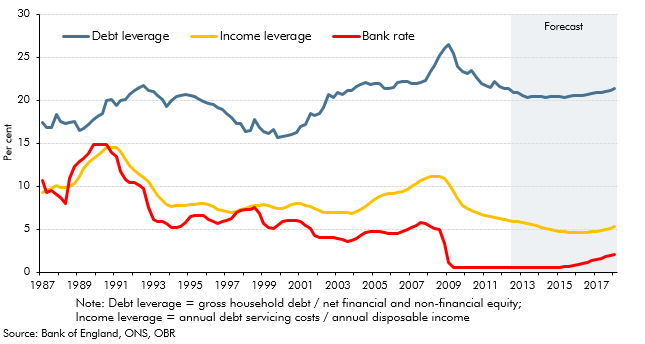

We expected debt servicing costs as a share of disposable income, or ‘income leverage’, to rise as our forecasts for house price inflation outstripped income growth and Bank Rate gradually increased. This box discussed the extent to which mortgage servicing costs were likely to increase over the forecast period and the implications of this for household behaviour, using information from the Bank of England/NMG survey.

The household saving ratio continued to rise in 2012. This box explored the possible reasons for this, considering evidence from the latest available NMG household survey. The box also discussed the implications for household balance sheets, noting that in aggregate households appeared to have used higher saving to finance accumulation of more financial assets, rather than paying down debt.

In each Economic and fiscal outlook we publish a box that summarises the effects of the Government’s new policy measures on our economy forecast. These include the overall effect of the package of measures and any specific effects of individual measures that we deem to be sufficiently material to have wider indirect effects on the economy. In our December 2012 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, we made adjustments to our forecasts of real GDP, inflation and property transactions

The Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS) was launched by the Bank of England and the Government in July 2012 to encourage banks and building societies to expand their lending by providing funds at lower rates than prevailing market rates. This box discussed the uncertainties associated with the transmission mechanism of this scheme and the possible impact on real GDP.

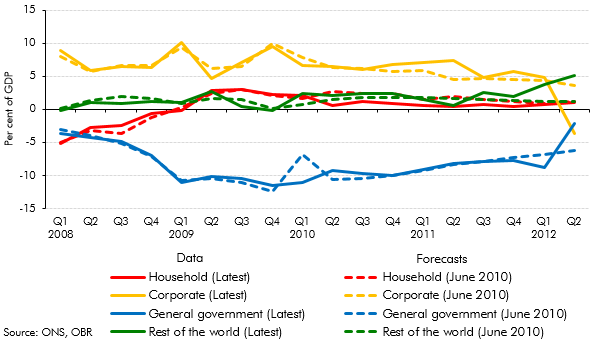

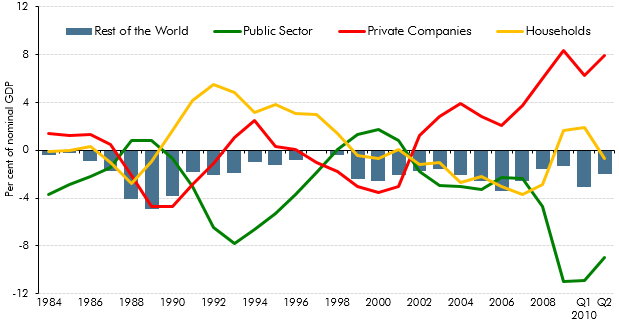

An alternative way to view the sectoral decomposition of the economy is to look at the financial balances of households, firms, government and the rest of the world. This box explored net lending by sector from 2008 to 2012, and how this compared with our June 2010 forecast

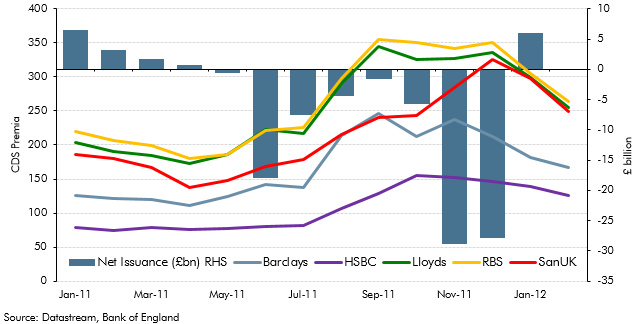

Central banks around the world launched two significant new market operations at the end of 2011. This included a program to provide liquidity support to the global financial system, as well as longer-term refinancing operations by the ECB. This box analysed the impact of these operations on the UK financial sector by looking at net capital issuance and five-year credit default swap (CDS) premia of UK banks. In light of these developments, we made adjustments to our forecast of CDS premia in our March 2012 forecast.

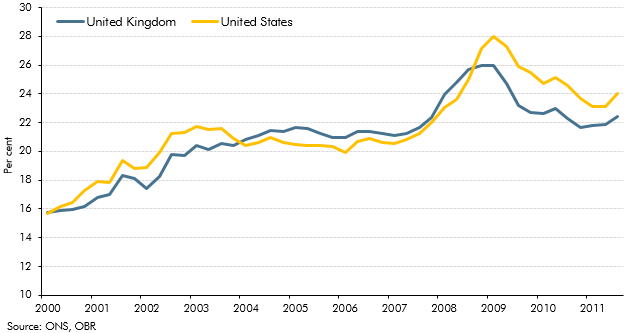

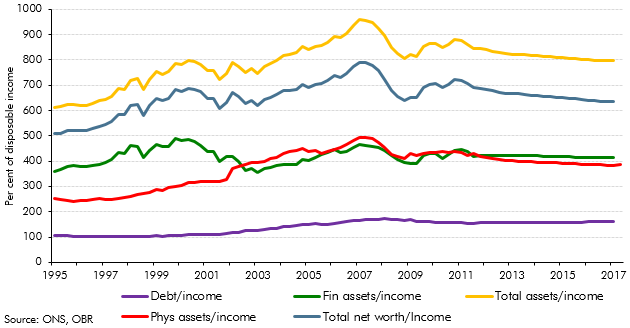

The path of the household debt-to income ratio since the crisis had led outside commentators to conclude that household deleveraging had further to run in the UK than the in the US. This box discussed some of the limitations of debt-to-income as a measure of leverage. An alternative measure is the debt to equity ratio - which takes into account both household assets and liabilities - which indicated that household leverage had fallen more slowly in the US than in the UK since the crisis.

Our November 2011 forecast implied that households would take on around £480 billion of additional debt over the forecast period. This box discussed the implications of this for the household balance sheet, noting that a large part of the increase in household debt reflects borrowing for the purchase of assets. The box also discussed the downward revision in our household debt forecast since our previous EFO, which was largely accounted for by a combination of higher saving and a weaker housing market outlook.

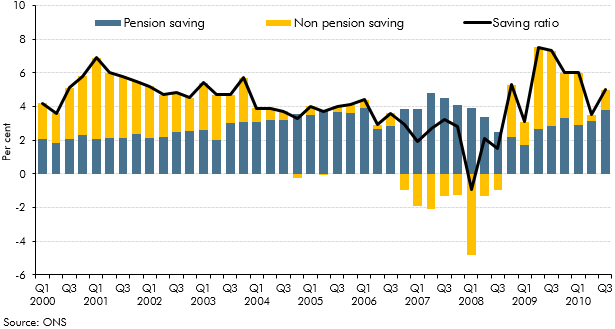

The household saving ratio captures both the disposable income that households do not spend on consumption, and changes in the equity households have in pension funds. This box described how the household saving ratio is calculated, and considered the relative contribution of pension and non-pension saving to the saving ratio over the preceding decade. The box also discussed possible factors behind recent movements in pension saving.

A rebalancing away from private consumption towards investment and net trade was a theme of our November 2010 forecast. This box set out the key features of domestic sector balances over the preceding two decades.