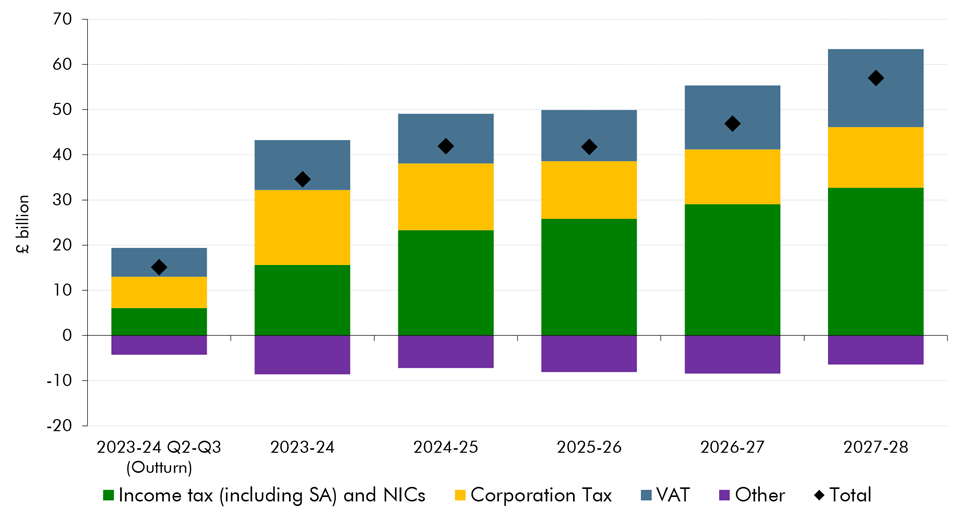

Taxes on different forms of consumer spending provide the second-biggest source of revenue for government, with VAT (value added tax) by far the biggest of those. In 2025-26 we estimate that VAT will raise £179.6 billion (this measure of excludes refunds of VAT made to certain public sector organisations). That represents 14.6 per cent of all receipts and is equivalent to around £6,250 per household and 5.9 per cent of national income.

VAT is levied on the purchase of many goods and services. It is reflected in the price paid when items are bought and is collected from traders. Unlike a simple sales tax, it is levied – as the name implies – on the amount of value added at each stage of the production chain. For example, a retailer would not be liable for the full amount of VAT if the good they sold had been purchased from a wholesaler.

The standard rate of VAT is 20 per cent, with around half of household expenditure subject to this rate. The reduced rate is 5 per cent and is applied to domestic fuel and power, children’s car seats and some other goods. Around 2.5 per cent of expenditure is taxed at this reduced rate. Other goods and services, such as books, newspapers, children’s clothing and many foods attract no VAT (i.e. they are either exempt from VAT or are ‘zero-rated’).