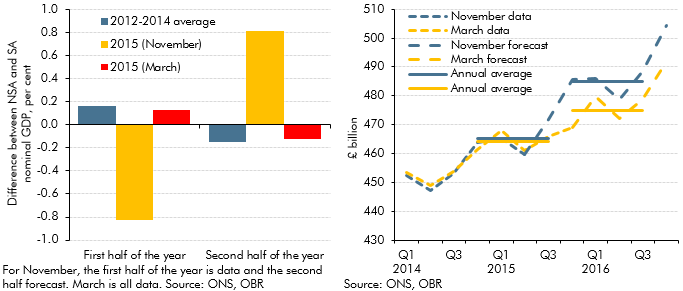

Most public discussion of economic prospects focuses on real GDP. But nominal GDP – and its composition by income and expenditure – is more important for understanding the behaviour of the public finances. For example, VAT is levied on the nominal price of goods and services, so VAT receipts are closely linked to nominal consumption spending. Increases in nominal investment also affect receipts by raising use of capital allowances, thereby reducing corporation tax receipts in the short term. As a large proportion of public spending is set out in multiyear cash plans (public services, grants and administration, and capital spending) or linked to measures of inflation (including benefits, tax credits and interest on index-linked gilts), it tends to fluctuate as a share of GDP when economic fluctuations cause nominal GDP to rise or fall. Nominal GDP is also the denominator when calculating fiscal aggregates as a share of national income, including those that are the subject of the Government’s fiscal targets.

Our nominal GDP forecast reflects all the judgements we make about prospects for real GDP and the GDP deflator, which are explained in other parts of this guide. While the forecast is primarily driven by the expenditure measure of GDP, our forecast of the income composition of nominal GDP is a key driver of our forecast for public sector receipts and acts as a useful diagnostic on the overall nominal GDP forecast.