In February 2017, just ahead of the Spring Budget and our March Economic and fiscal outlook, the Ministry of Justice announced that the ‘personal injury discount rate’ would be reduced from 2.5 to minus 0.75 per cent (in inflation-adjusted real terms). This box explained the direct and indirect effects of this change on our receipts and public spending forecasts.

In February, the Ministry of Justice announced that the personal injury discount rate would be reduced from 2.5 to minus 0.75 per cent (in inflation-adjusted real terms). This discount rate is used when calculating lump-sum awards in respect of financial loss due to personal injury. A lower discount rate increases the net present value of projected future flows, leading to higher awards. At the same time, the Government announced that it would launch a consultation that “will consider whether there is a better or fairer framework for claimants and defendants”. The effect of any policy changes that follow will be reflected in future forecasts.

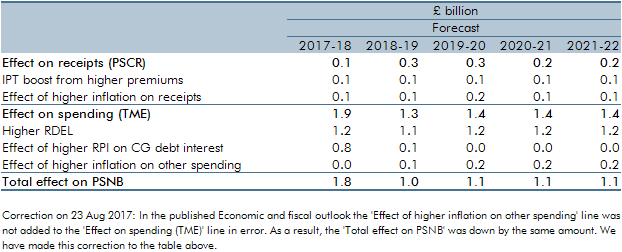

As Table A shows, reducing the discount rate has three effects on our fiscal forecast:

- the Government has added around £1.2 billion a year to the RDEL reserve to meet the expected costs to the public sector, in particular to the NHS Litigation Authority;

- an expected increase in IPT receipts of around £0.1 billion a year as the increased costs for the insurance industry, particularly in the motor sector, are passed on in higher premiums. We assume that these costs will be fully passed on to consumers, raising motor insurance premiums by around 10 per cent this year (although this is highly uncertain). It may also have pushed premiums up in recent months, as the industry anticipated a change. We also assume that this change will raise the cost of public and employer liability insurance. Our estimate of the IPT effect allows for consumers responding to higher prices by reducing the value of their coverage; and

- higher insurance premiums will increase inflation – directly in the case of motor insurance and indirectly via costs to business in the case of employer liability insurance. As set out in Box 3.2, the effect is around four times bigger on RPI than CPI inflation due to differences in the weight of motor insurance in each index. The biggest effect via RPI inflation is to push up the cost of accrued interest on index-linked gilts, increasing borrowing by £0.8 billion in 2017-18 and £0.1 billion in 2018-19. There is a smaller but persistent RPI effect via the revalorisation of excise duties, while higher CPI inflation also leads to changes to tax and benefit thresholds. Together these effects are largely offsetting.

Table A: Lowering the personal injury discount rate: estimated fiscal effects

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2017