We expected debt servicing costs as a share of disposable income, or ‘income leverage’, to rise as our forecasts for house price inflation outstripped income growth and Bank Rate gradually increased. This box discussed the extent to which mortgage servicing costs were likely to increase over the forecast period and the implications of this for household behaviour, using information from the Bank of England/NMG survey.

This box is based on ONS income data from October 2013 .

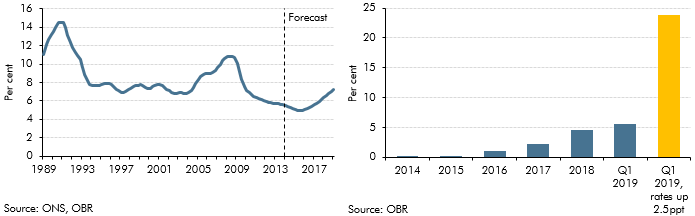

We expect house price inflation to outstrip income growth in the near term, which is consistent with an increase in the average size of mortgages and household debt relative to income. Combined with a gradual increase in Bank Rate, of 2.5 percentage points by Q1 2019, this means debt servicing costs as a share of disposable income, or ‘income leverage’, will rise. But our central forecast assumes only a 0.8 percentage point rise in average mortgage rates over the same period, as spreads narrow to more historically normal levels. So although mortgage servicing costs are likely to rise, we expect them to remain close to pre-crisis averages (Chart E).

Chart E: Household income leverage (left) and Chart F: Share of mortgagors reacting to rising debt servicing costs (right)

Chart E shows whole economy income leverage over the forecast period, but the effect of rising interest rates will be felt more by some than by others. Survey data compiled for the Bank of England show that two-thirds of households may be less negatively affected by rising interest rates because they do not have a mortgage. Indeed, if they have savings, they would be positively affected. Of the remainder, those who start with high income leverage tend to be more exposed to rate increases than those with low income leverage, because they have larger mortgages.a, b

Using survey responses to the question “About how much do you think your monthly mortgage payments could increase for a sustained period without you having to take some kind of action to find extra money e.g. cut spending, work longer hours, or request a change to your mortgage?”, we can simulate what our forecast might mean for aggregate household behaviour.c Chart F is constructed by assuming respondents’ mortgage debt, income and mortgage interest rate grow in line with our aggregate forecast and that the threshold is also adjusted over time for rising income. On this basis, our central forecast is consistent with 5.5 per cent of households with a mortgage changing their behaviour by Q1 2019 because debt servicing costs have risen. This reflects the fact that both interest rates and incomes are forecast to rise as the economy recovers.

Our central forecast assumes mortgage rates rise more slowly than Bank Rate. If mortgage rates were to rise by 2.5 percentage points by Q1 2019, in line with our central assumption for Bank Rate, the effect on borrowers could be more significant, with 24 per cent of mortgagors changing behaviour. This illustration assumes household debt grows in line with our central forecast. An increase in mortgage interest rates of 2.5 percentage points, without more income growth, would almost certainly reduce household demand for debt. The proportion of households needing to respond to higher interest rates would be significantly lower if that were the case. Faced with a larger rise in debt servicing costs, households could change their behaviour in a number of ways, as described in the survey question. In practice, the aggregate response would include a combination of these. We explore the consequences of shocks to interest rates in Chapter 5.