The accounting treatment applied to the burgeoning stock of student loans has been the subject of much interest over the past year, with reports from the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee and the Office for National Statistics. In July, we published our own contribution in Working Paper No. 12: Student loans and fiscal illusions. In this box we analysed the possible impacts of different accounting treatments on our estimate of the deficit.

The accounting treatment applied to the burgeoning stock of student loans has been the subject of much interest over the past year, with reports from the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee and the Office for National Statistics.a In July, we published our own contribution in Working Paper No. 12: Student loans and fiscal illusions. These illusions occur when the treatment of a transaction in the National Accounts does not reflect its true implications for the public finances. We noted several aspects of the current treatment create such illusions: the valuation of the loan asset; the deficit impact of sales; and the deficit impacts of the extension of the loans and the interest charged on them. For the latter two in particular, we reviewed potential alternative accounting treatments.

Student loans are designed to have a significant level of subsidy: repayments are contingent on income and it is the policy intent that lower earners will repay only a portion of their loans and associated interest (at most). In the case of full-time students in England receiving Plan 2 loans (the larger ones in place since tuition fees were raised in 2012), our latest projection suggests that only 38 per cent of the total principal and interest charged to students will be repaid. The current accounting treatment does not recognise this subsidy element for many decades, instead:

- all outlays are treated as loans assets (with no impact on the deficit) – even though most of the outlays will never be recovered;

- all interest charged is treated as income (benefitting the deficit) – even though most of this income will never actually be received; and

- the low rates of recovery lead to large future write-offs (30 plus years away for English Plan 2 loans) far beyond our medium-term forecast horizon and Governments’ normal planning windows.

Of the methods investigated in the paper, two were found to offer significant improvements on the current treatment and to be compatible with the National Accounts. The first noted that from the point of view of the recipient, student loans were much like a tax, so could be treated as revenue (for the cash received) and spending (for the outlays). This treatment would be very simple in practice as it reflects observable cash flows. However, by assuming that all outlays are spending, it ignores the fact that a significant portion of outlays do genuinely resemble loans.

The second method was a hybrid between a ‘revenue and expenditure’ approach and the current ‘loans’ approach. It would reflect the economic reality of student loans by dividing outlays into loans and grants – reflecting the subsidy element – and then only charging interest on the loan portion. The aim would be to judge the split so there were no write-offs to record at the end of the loan’s life. While this is economically sound, it would be difficult to implement as it would rely on uncertain projections of flows over the lifetime of a loan to estimate the division.

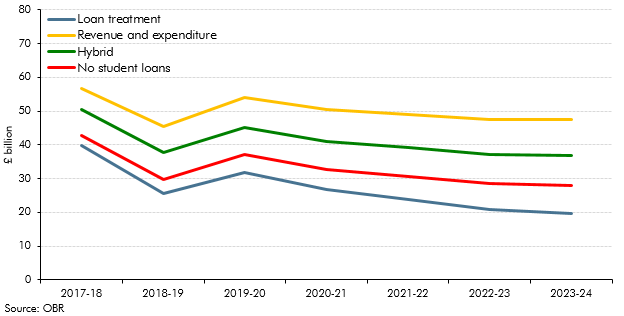

Chart A shows our central forecast for public sector net borrowing under the current accounting treatment and illustrative paths under the two alternative methodologies. It also provides a baseline illustration of how the deficit would evolve in the absence of any student loan-related receipts or spending. The analysis is largely based on the detailed cohort data that underlies our English Plan 2 student loans forecast. Due to the scale of the Plan 2 outlays (accounting for 86 per cent of total UK outlays over the forecast) and the larger Plan 2 subsidies (62 per cent of expected write-offs over their lifetime compared to an estimated 19 per cent for non-Plan 2), the analysis is dominated by the Plan 2 loans.b

Chart A: PSNB under different treatments of student loans

As Chart A shows, the current loans treatment reduces the deficit by steadily increasing amounts across the forecast (reaching £8.2 billion in 2023-24), compared to a ‘no loans’ counterfactual. This reflects interest accrued on the increasing stock of loans, with very little offset from write-offs. On the ‘revenue and expenditure’ basis, student loans become progressively more expensive across the forecast, raising the deficit by £19.5 billion in 2023-24 (with £22.7 billion of outlays partly offset by £3.3 billion of repayments). The ‘hybrid’ treatment adds to borrowing too, but by less and has a flatter profile – rising slowly to £8.9 billion in 2023-24 (with £12.6 billion of expenditure offset by £3.7 billion of interest receipts).

The difference between the current treatment and our estimate of the hybrid treatment illustrates the extent of the fiscal illusion created by the current approach. It suggests the current treatment flatters the deficit by £12.3 billion in 2018-19 and £17.1 billion in 2023‑24. In the Government’s fiscal target year of 2020-21, the difference is £14.4 billion – just less than the margin by which it is set to meet its self-imposed ‘fiscal mandate’.

The ONS has been working with international agencies and other national statistical institutes since the spring on potential revisions to the accounting guidance for income contingent loans and aim to provide an update on progress in December. We will then consider whether to make any adjustments to our forecasts at the Spring Statement. Any methodological change will be made after discussions with ONS. It is quite possible that the ONS’s eventual methodology will differ from those presented here or in our working paper.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – October 2018