In 2022-23 we have seen sharp rises in gas prices and interest rates, both of which are forecast to remain elevated in 2023-24. This box presented the potential fiscal impacts of a higher-than forecast path for gas prices and two scenarios where Bank Rate is either a percentage point higher or lower than in our central forecast.

The two most important drivers of changes to the economic outlook since our March forecast have been higher energy prices and higher interest rates. Prospects for both remain key sources

of risk to the economic and fiscal outlook in the near and medium term.

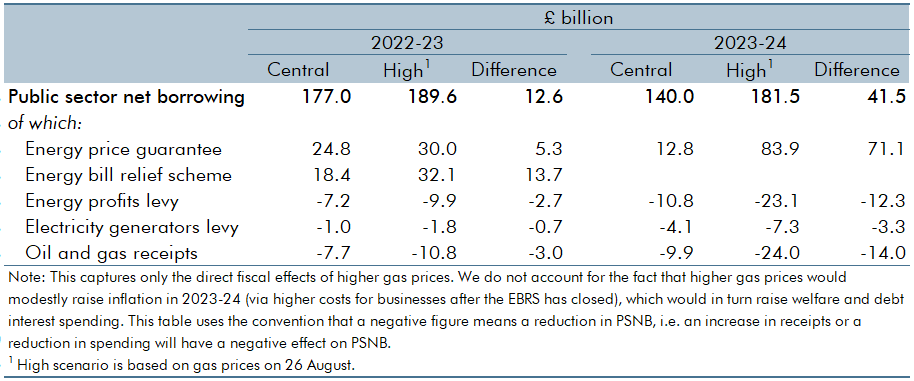

The limits placed on energy costs by the EPG (for households over eighteen months) and EBRS (for businesses over six months) mean that near-term volatility in energy prices principally affects the fiscal outlook directly via its implications for spending. To illustrate this risk, Table A shows how the late-August peak in gas prices (shown at the top of the blue swathe in the top-left panel of Chart 3) would affect the direct fiscal cost of these energy support schemes, while also accounting for the partially offsetting effects on taxes levied on oil and gas producers and energy

generators. (Given the gas prices on which our fiscal forecast is conditioned are close to their lowest over the past three months, we present a higher gas price scenario only.) Borrowing

would be higher by £12.6 billion this year and £41.5 billion next year on those peak gas prices (of around £8 a therm this winter and £7 a therm over 2023-24). In 2022-23, a third of the higher cost of support measures is offset by higher tax receipts, rising to two-fifths in 2023-24.

Beyond the life of these energy support schemes, movements in energy prices in a net-energy-importing economy like the UK also affect the fiscal outlook indirectly via higher or lower

inflation, which would in turn weaken or strengthen GDP growth. And in the medium term they affect potential output, with each 10 per cent rise in gas prices (with oil prices unchanged) reducing the level of potential output by up to 0.1 per cent.a

Table A: Implications of higher gas prices for near-term borrowing

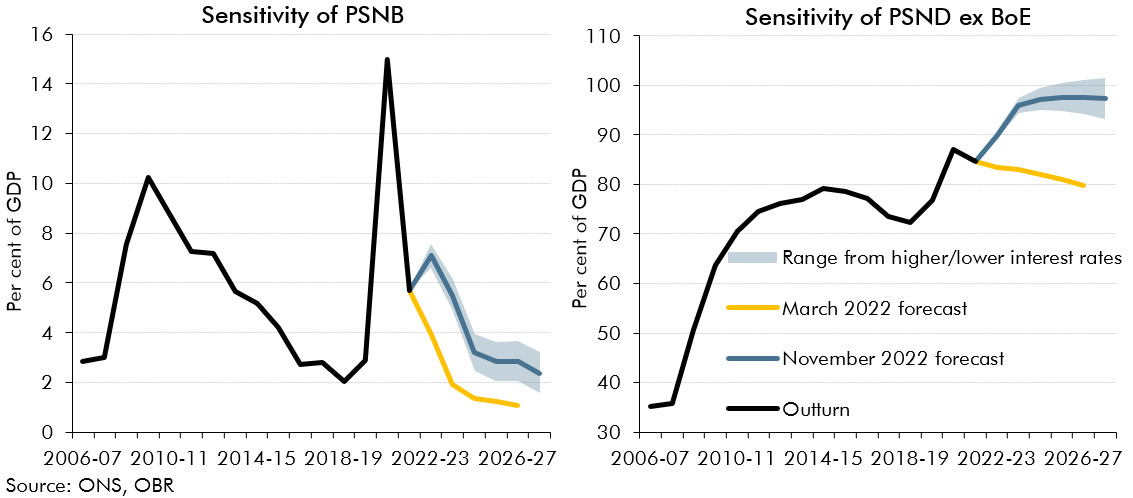

To illustrate the fiscal risks from changes in interest rates over the medium term, Chart E summarises the borrowing and debt impacts of a stylised 1 percentage point increase or decrease in interest rates at all maturities.b In addition to their direct impact on the cost of servicing the public debt (which is set to exceed 100 per cent of GDP) higher or lower rates feed through to mortgage rates, house prices, consumption and investment, lowering or raising GDP by 0.4 per cent at the forecast horizon. This feeds through to tax revenues via the housing market and the wider economy, and more directly through interest and dividend receipts, and income tax on savings income. This results in borrowing being around £25 billion higher or lower and underlying debt around 4 per cent of GDP higher or lower in 2027-28.

Relative to our central forecast, this stylised scenario suggests that interest rates would need to be just 0.4 percentage points higher to wipe out the £9.2 billion margin by which underlying debt is falling in the final year of the forecast. But equally, a fall of just 0.4 percentage points would double the Chancellor’s headroom relative to our central forecast.

Chart E: Sensitivity of PSNB and underlying debt to interest rates

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2022