In each Budget or Autumn Statement, there are typically lots of policy giveaways (tax cuts or spending rises) and takeaways (tax rises or spending cuts). The net effect of these will be to raise or reduce borrowing in specific years and on average over the five years of the forecast – in other words to loosen or tighten fiscal policy. In this box from our 2017 Fiscal risks report we considered the pattern of those policy changes since 2010, noting that near-term giveaways are often financed by the promise of medium-term takeaways.

One reason our borrowing forecasts change in each Economic and fiscal outlook is that we incorporate the impact of the policy decisions announced in the Chancellor’s Budget or Autumn Statement (the ‘fiscal event’). These include the tax and spending decisions reported on the Treasury’s ‘scorecard’ plus other changes – typically to departmental spending – that it chooses not to report in this way. There are typically lots of giveaways and takeaways in each event, the net effect of which is to raise or reduce borrowing in specific years and on average over the five years of the forecast – in other words to loosen or tighten fiscal policy.

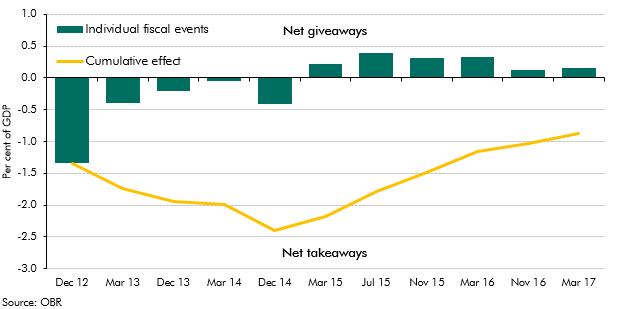

One pattern in the 15 fiscal events since the Coalition’s June 2010 Budget is the tendency for governments to announce giveaways in the near term, but with the promise that they will be recouped by takeaways in the later years. Chart A shows the average tightening or loosening by year in all fiscal events from Spending Review 2010, and separately for each of the two previous Parliaments. The pattern of early giveaways and later takeaways is clearest under the previous Conservative Government, with near-term neutrality followed by later takeaways the average pattern under the Coalition.

There is of course considerable variation within these averages: March 2015 included a large spending giveaway in year 5 to ensure that spending was not projected to fall to its lowest share of GDP since the 1930s; July 2015 had a particularly uneven path of spending revisions as the resulting ‘rollercoaster’ profile was smoothed out and spending was raised overall.

Chart A: The average effect of Government decisions on borrowing

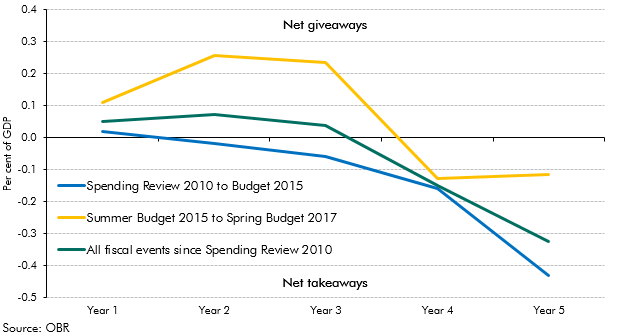

The fiscal risk associated with early promises of fiscal tightening being eroded as the year in question draws closer can be illustrated by looking at the effect on borrowing in 2017-18 of the policy decisions made at successive fiscal events. This year first entered the forecast window in December 2012, at which point the Coalition decided that spending should fall sufficiently as a share of GDP to meet its deficit target. In the 11 fiscal events since then around 600 scorecard policy decisions, plus other changes to spending, have affected our forecasts for borrowing in 2017-18. Chart B shows how further tightening was layered on until Autumn Statement 2014, after which point every subsequent fiscal event included net giveaways. The cumulative effect of these was to reverse two-thirds of the peak tightening and one-third of the initial tightening. This Autumn’s Budget could change the final position once more.

This switch from takeaways to giveaways did not occur because the underlying forecast for the public finances had improved in such a way that the earlier takeaways had proved unnecessary. Rather the Government has become less ambitious for net borrowing. In Autumn Statement 2012 the Coalition had set its spending plans consistent with achieving a structural budget deficit of 0.3 per cent of GDP in 2017-18; by Autumn Statement 2014 that was little changed at 0.5 per cent; whereas the Conservative Government opted for one of 2.9 per cent of GDP in March.

Chart B: The effect of Government decisions on borrowing in 2017-18