The successful vaccine rollout has allowed the economy to reopen largely on schedule, despite continuing high numbers of coronavirus cases. The vaccines’ high degree of effectiveness, combined with consumers’ and businesses’ surprising degree of adaptability to public health restrictions, has meant that output this year has recovered faster than we expected in March, boosting tax revenues in the process. The stronger economic recovery has also helped to reduce the fiscal cost of pandemic-related support to below our March forecast. The economy is now expected to grow by 6.5 per cent in 2021 (2.4 percentage points faster than we predicted in March), and unemployment to rise only modestly to 5¼ per cent this winter (1¼ percentage points lower than March), which helps the budget deficit to almost halve to £183 billion in 2021-22 (£51 billion lower than March).

But the strength of the rebound in demand in the UK and internationally has led it to bump up against supply constraints in several markets. In the UK, these supply bottlenecks have been exacerbated by changes in the migration and trading regimes following Brexit. Energy prices have soared, labour shortages have emerged in some occupations, and there have been blockages in some supply chains. These can be expected to hold back output growth in the coming quarters, while raising prices and putting pressure on wages. We expect CPI inflation to reach 4.4 per cent next year, with the risks around that tilted to the upside. News since we closed our forecast would be consistent with inflation peaking at close to 5 per cent next year. And it could hit the highest rate seen in the UK for three decades.

Over the medium term, we have revised up real GDP as we now expect post-pandemic scarring of potential output to be 2 per cent – rather than the 3 per cent we assumed in March. Uncertainty around this judgement remains large, however, with limited evidence as yet regarding how smoothly furloughed workers will be reabsorbed into employment, whether those workers who became inactive or left the country during the pandemic will re-enter the labour force, and how fully shortfalls in capital investment, innovation, and the acquisition of skills will be made up. With inflation also higher and more persistent, we have revised up nominal GDP – the key driver of tax revenues – by 4.1 per cent in 2025-26 relative to March, boosting our pre-measures revenue forecast by 4.5 per cent in that year. While higher inflation also boosts public spending, overall our pre-measures forecast for borrowing is lower by £38 billion a year on average relative to our March forecast.

Against the backdrop of an improved underlying fiscal outlook, the Government has announced a significant discretionary increase in both the tax burden and the size of the post-pandemic state. In particular, the October 2021 Budget and Spending Review delivers:

- A further net tax rise amounting to £16.7 billion a year by 2026-27, more than explained by the introduction of a health and social care levy of 1.25 per cent on employees, employers and the self-employed, which raises £18.2 billion by 2026-27, and is only partly offset by tax cuts, principally the freezing of fuel duty for the twelfth year in succession at a cost of £1.6 billion a year. Together with the £31.5 billion in corporate and personal tax increases announced in the March 2021 Budget, and the improved underlying fiscal outlook, these measures raise the tax burden from 33.5 per cent of GDP before the pandemic to 36.2 per cent of GDP by 2026-27, its highest since the early 1950s. Taking his March and October Budgets together, the Chancellor has raised taxes by more this year than in any single year since Norman Lamont and Ken Clarke’s two 1993 Budgets in the aftermath of Black Wednesday.

- A large and sustained increase in public spending amounting to £22.9 billion a year in 2026-27, comprising a £25.0 billion increase in departmental resource spending and a £3.0 billion boost to universal credit, which is only partly offset by £6.7 billion saved by the temporary move from a triple to double lock for the state pension. Of the roughly £30 billion on average added to departmental budgets in each year of the Spending Review, around half goes directly from the new levy to health and social care with the other half undoing the £18 billion of unspecified cuts to pre-pandemic spending totals made in the last two fiscal events. Together with underlying forecast changes, these discretionary increases take public spending from 39.8 per cent of GDP before the pandemic to 41.6 per cent of GDP in 2026-27, the largest sustained share of GDP since the late 1970s.

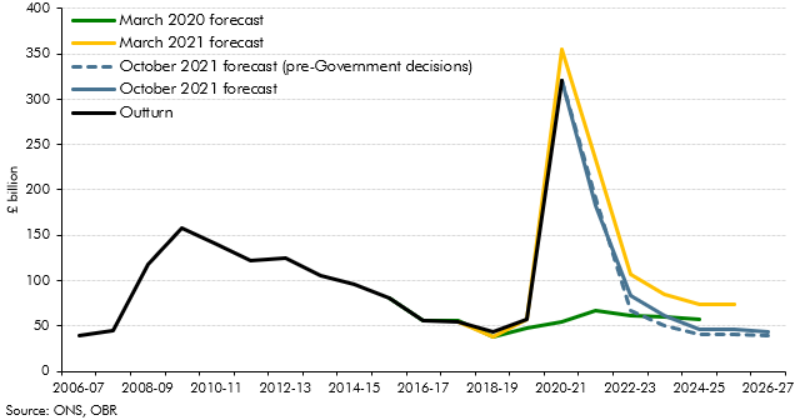

Taking account of both forecast and policy changes announced since March, borrowing falls back below £100 billion next year, declining more slowly thereafter to stabilise at around £44 billion (1.5 per cent of GDP) in the medium term. This leaves borrowing lower in every year than we forecast in March, and down £27 billion in 2025-26 thanks to the £33 billion improvement in the pre-measures fiscal outlook being only partly offset by a net fiscal loosening that declines to £6 billion by that point (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Public sector net borrowing

The improvement in the fiscal outlook is sufficient to enable the Chancellor to meet his fiscal target of getting underlying debt falling as a share of GDP by the third year of our forecast (2024-25 in this one). This new fiscal mandate is codified in a revised draft Charter for Budget Responsibility published alongside the Budget, which also includes supplementary targets for balancing the current budget within three years and capping public investment and welfare spending over different periods. All these new targets are set to be met too. Finally, the Charter identifies additional measures of debt affordability and public sector balance sheet performance that will guide the Chancellor’s management of fiscal policy. In our central forecast, underlying debt falls by 0.6 per cent of GDP in 2024-25, the current budget is in surplus by 0.9 per cent of GDP, public investment averages 0.3 per cent of GDP below its cap, and welfare spending is £2.8 billion below its effective cap. These margins are all well below the historical average three-year ahead forecast error for the current balance of 2.3 per cent of GDP and for the change in debt of 3.8 per cent of GDP.