Two years since the start of the pandemic, this Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) is presented against the backdrop of another unfolding global shock. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is foremost a human tragedy and a reminder of the terrible costs of wars and the immense and immeasurable losses for those caught up in them. The conflict also has major repercussions for the global economy, whose recovery from the worst of the pandemic was already being buffeted by Omicron, supply bottlenecks, and rising inflation. A fortnight into the invasion, gas and oil prices peaked over 200 and 50 per cent above their end-2021 levels respectively. Prices have since fallen back but remain well above historical averages.

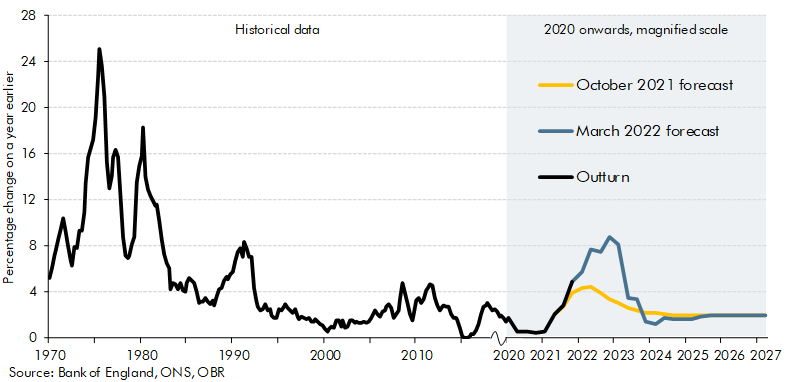

As a net energy importer with a high degree of dependence on gas and oil to meet its energy needs, higher global energy prices will weigh heavily on a UK economy that has only just recovered its pre-pandemic level. Petrol prices are already up a fifth since our October forecast and household energy bills are set to jump by 54 per cent in April. If wholesale energy prices remain as high as markets expect, energy bills are set to rise around another 40 per cent in October, pushing inflation to a 40-year high of 8.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2022 (Chart 1). Higher inflation will erode real incomes and consumption, cutting GDP growth this year from 6.0 per cent in our October forecast to 3.8 per cent. With inflation outpacing growth in nominal earnings and net taxes due to rise in April, real livings standards are set to fall by 2.2 per cent in 2022-23 – their largest financial year fall on record – and not recover their pre-pandemic level until 2024-25.

Chart 1: CPI inflation

Despite these economic headwinds, the public finances have continued to recover from the pandemic more quickly than we expected. Tax receipts this year have been revised up by 4 per cent thanks to strong growth in tax paid by higher earners and by companies. And despite higher inflation pushing up debt interest costs, borrowing is set to more than halve from its post-World War II high of £322 billion (15.0 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21 to £128 billion (5.4 per cent of GDP) in 2021-22, £55 billion less than we forecast in October.

Borrowing in 2022-23 is then £16 billion higher than we forecast in October, at £99 billion (3.9 per cent of GDP). That reflects record-high debt interest costs of £83.0 billion, double our October forecast, and near-term rebates and tax cuts that inject £17.6 billion into the economy. The latter offset half the blow to household finances from higher energy and fuel bills and a third of the overall fall in living standards that households would otherwise have faced. Over half the £9 billion in energy costs support is recouped over the subsequent five years, while the 5p fuel duty cut is to be more-than-fully reversed next year. The ‘pay later’ phase of these measures comes when energy bills are set to fall back.

Before taking account of the policies in this Spring Statement, positive news since October has led us to revise up receipts by £37 billion in 2024-25 – the Government’s fiscal target year. Higher inflation and interest rates mean nearly two-thirds of that is consumed by higher spending (revised up £23 billion in 2024-25), leaving a net £14 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP) pre-measures borrowing windfall. Student loans reforms that reduce the share of loan balances expected to go unpaid free up a further £5 billion, leaving almost £20 billion of fiscal room for manoeuvre in the target year at this Spring Statement. Cuts to personal taxes costing £10 billion consume just over half of that, with the remainder reducing borrowing. In the process the Chancellor has undone just over a quarter of the overall value of the personal tax rises he announced last year and around a sixth of the overall net tax rises he has announced since becoming Chancellor.

Public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England falls by 1.0 per cent of GDP in 2024-25, a margin of £27.8 billion against the Government’s fiscal mandate, £10.3 billion greater than in our October EFO. And the current budget is in surplus by £31.6 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP), up £6.5 billion from October. History suggests these margins would be consistent with a 58 and 66 per cent chance of meeting each fiscal target respectively, broadly in line with the headroom previous Chancellors have given themselves.

But few of these fiscal targets were actually met in the past and there are numerous risks to the outlook at present. Higher energy prices and inflation as a result of a longer war in Ukraine or tougher international sanctions would reduce the Chancellor’s headroom by over £4 billion in our illustrative scenario. There could be pressure to: provide further support for households in the event of another large rise in the energy price cap in October; address the 5 per cent fall in the real value of welfare benefits in 2022-23; or cancel next year’s fuel duty super-indexation that would raise petrol prices 6 per cent overnight and be the first duty increase in 12 years. In the medium term, a sustained increase in global energy prices could lower potential output for a net energy importer like the UK, damaging fiscal prospects. And while successful vaccines have reduced pandemic-related uncertainties, the recent rise in hospitalisations demonstrate that Covid remains a risk.