Economic growth in the UK and globally has slowed since the Budget in October, leading us to revise down our near-term GDP forecast. But tax receipts have performed better than we expected in the final months of 2018-19 and we judge that much of this buoyancy will endure. Together with downward pressure on debt interest spending from lower market interest rates, this delivers a modest medium-term improvement in the public finances. The Chancellor has banked most of it in lower borrowing, but has spent some on higher planned public services spending. Of the six forecasts we have produced since the EU referendum, four have shown an improved outlook for the public finances and two have shown a deterioration – but each one has been accompanied by some fiscal giveaway.

This forecast has been produced against the backdrop of considerable uncertainty over the next steps in the Brexit process. With discussions in Brussels continuing and Parliament scheduled to vote on various Brexit-related questions in the week of the Spring Statement, we have no meaningful basis for changing the broad-brush assumptions that have underpinned our forecasts since the referendum. So we continue to assume – consistent with government policy at the time we finalised our forecast – that the UK makes an orderly departure from the EU on 29 March into a transition period that lasts to the end of 2020.

Alternative outcomes, including a disorderly ‘no deal’ exit, remain the biggest short-term risks to the forecast. But the smoothness, or otherwise, of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU is but one step in the Brexit process, as negotiations on the terms of the UK’s future relationship with the EU have yet to begin in earnest. So many decisions remain to be taken that will help determine the eventual impact of Brexit on the economy and public finances.

The economy ended 2018 growing a little less strongly than we expected in October. In recent weeks survey indicators of current activity have weakened materially, in part reflecting heightened uncertainty related to Brexit. As a result, we have revised our forecast for GDP growth this year down to 1.2 per cent – more than reversing the upward revision we made in October in response to the Government’s discretionary fiscal loosening in the Budget. But we have not altered our assessment of the outlook for potential output, so our medium-term forecast is little changed: GDP growth still settles down to around 1½ per cent a year.

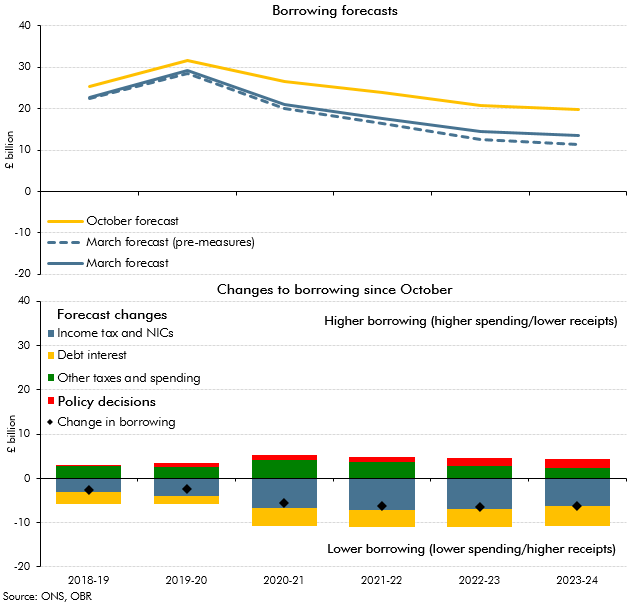

We now expect public sector net borrowing to come in at £22.8 billion (1.1 per cent of GDP) this year, down £2.7 billion since October thanks primarily to higher income tax receipts and lower debt interest spending. By 2023-24 the improvement since October is £6.3 billion, again thanks primarily to higher income tax receipts and lower debt interest spending (Chart 1). These downward pressures on borrowing are partially offset by the £2.1 billion net cost of 20 policy decisions announced since the Budget – notably the £1.7 billion of additional planned public services spending announced at the Spring Statement. This leaves the expected deficit in 2023-24 at £13.5 billion (0.5 per cent of GDP).

Chart 1: Public sector net borrowing: March versus October

The Government’s stated ‘fiscal objective’ is to balance the budget by 2025-26 and past forecast performance suggests that it now has a 40 per cent chance of doing so by the end of our forecast in 2023-24. But in the years beyond the forecast the ageing population is likely to be putting increasing upward pressure on spending and the potential impact of different Brexit outcomes makes the medium-term outlook more than usually uncertain. In particular, our past scenario analysis has illustrated the importance of medium-term potential growth rates – both productivity growth and the contribution of net migration to population and employment growth – to medium-term fiscal health. Uncertainty around these judgements is always significant, but Brexit only makes it more so.

As regards the Government’s other fiscal targets, the forecast changes and policy decisions leave the Chancellor with £26.6 billion (1.2 per cent of GDP) of headroom against his fiscal mandate, which requires the structural budget deficit to lie below 2 per cent of GDP in 2020-21. This is up from £15.4 billion in October, as the fiscal costs of the temporary near-term cyclical weakness of the economy have been swamped by the fiscal gains from higher income tax and lower debt interest spending. The Chancellor also meets his supplementary target of reducing net debt as a share of GDP in 2020-21. In this forecast it falls by 3.2 per cent of GDP in that year, unchanged from October. (The ending of the Bank of England’s Term Funding Scheme contributes 2.2 percentage points of the decline.)

One risk to the public finance metrics that we do expect to crystallise over the coming months is an improvement in the accounting treatment of student loans. From September the Office for National Statistics will treat them partly as loans and partly as grants, reflecting the fact that a large proportion of the loan outlays and associated interest are not expected to be repaid. We do not yet know exactly how this will be done, so cannot reflect the change in our central forecast. But we estimate that it could increase the structural budget deficit by around £12 billion or 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2020-21. This would absorb almost half the Government’s current headroom of 1.2 per cent of GDP against the fiscal mandate as well as making a balanced budget harder to achieve.

Read more in the March 2019 Economic and fiscal outlook