The introduction of universal credit (UC) is one of the most significant reforms to the welfare system since the Beveridge Report. It will replace six existing means-tested benefits and tax credits for people of working age, paying more than £60 billion a year to around 7 million households by the time it is fully rolled out.

The move to UC has been – and remains – an enormous design and delivery challenge for the Government, notably the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). The rollout has already been delayed repeatedly. And UC is now designed to save money, relative to the legacy system it replaces, rather than to cost more, as in the original vision. A welfare reform of this scale and nature is also a huge forecasting challenge and a source of significant risk to the Treasury in terms of public spending control.

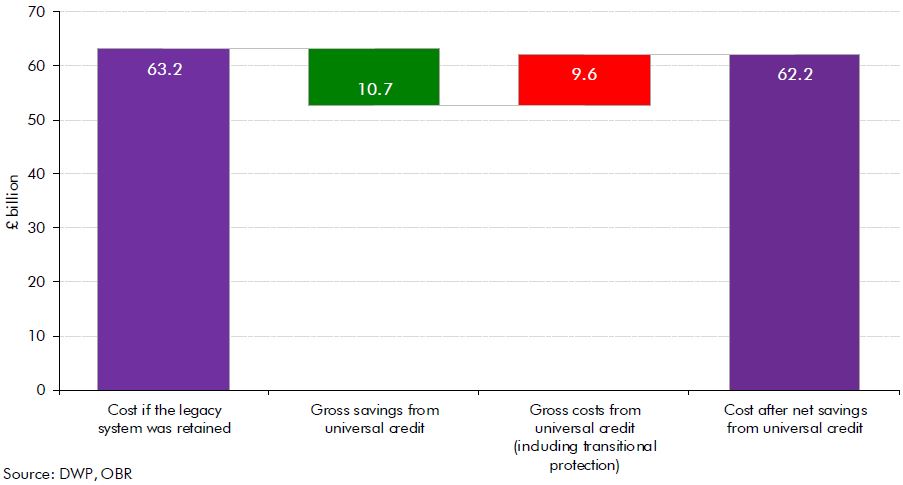

At first glance, the implications of UC for the public finances look modest. In the absence of the reform, we estimate that the legacy system would cost £63.2 billion in 2022-23. On the current design, UC would reduce that by £1.0 billion. But this small saving is the net effect of £10.7 billion of gross savings and £9.6 billion of gross costs. (The underlying net saving is a slightly larger £2.3 billion, if you exclude £1.3 billion of temporary payments to some people moved to UC.) If any errors predicting these gross savings and costs add to rather than offset each other we could see large errors in the forecast for overall spending.

Universal credit and the legacy system in 2022-23

Many of the features of UC that lead to these costs and savings are highly uncertain in their impact. This arises from the uncertain outlook for the economy and labour market, the complexity of modelling the new system with limited information and sometimes poorly integrated models, and the difficulty of predicting how people’s behaviour will respond to altered financial incentives and the wider imposition of conditions on claimants.

The introduction of UC will see conditions extended to claimants in work for the first time (as well as to more out-of-work claimants). DWP’s ‘work coaches’ must decide whether claimants are working sufficient hours or earning enough to receive UC (or, if they are self-employed, whether they are ‘gainfully’ so). The coaches will have discretion over the conditions and will be able to impose sanctions if they are not met. Much will depend on how they operate in practice and if their decisions are challenged.

Assessing the cost of UC once it is fully rolled out is difficult enough, but forecasting exactly how spending will evolve over the remaining five-year transition brings additional challenges – not least because the pace and composition of the roll-out is uncertain and only partly under government control. Migration of claimants to UC is already making it hard to interpret spending data in real time, as DWP cannot tell us what the UC recipients would have been receiving in the legacy system. This will become more of a problem as the overlap widens. This information gap will also make it harder to evaluate the impact on spending after the event, for example via changes to entitlement and take-up.

DWP has several trials underway to understand how UC will affect claimants’ labour market outcomes, arguing that it will deliver additional savings and economic benefits by getting more people into work and onto higher earnings. Studies to date find modest, but positive effects. But we have not yet incorporated these into our forecasts, as it is not yet clear that the impact found for the simple cases migrated so far will be replicated for the more complex ones to come or if the resources devoted to the early cases will be sustained.

The quantitative analysis in this report is based on the current policy design for UC, albeit with some elements still to be finalised. But, as we have seen on repeated occasions since UC was originally launched, this and future governments may well make further changes to the design. In that context, it is worth noting that some of the largest projected savings from UC come from self-employed recipients and that there will be winners and losers from changes in the way UC supports disabled people. In recent years both groups have been affected by Budget measures that the Government has subsequently reversed.

The introduction of UC is a radical reform, simplifying the financial incentives and administration of the welfare system in several important respects. We believe that our forecast for spending on UC is central, given the current policy design and the information and models available to us. But the experience of past – typically smaller – welfare reforms is that they often take longer than expected to deliver, save less than anticipated and create political pressure to compensate losers.