In the event of a 'no-deal' Brexit, the UK would be able to apply its own external tariff to goods imported. In this box, we explored the impacts of customs duties on borrowing, what a preliminary estimate of potential revenues would be and what else we would need to consider if this were to be our central forecast.

This box is based on OBR data from July 2019 .

In a no-deal Brexit, the UK would be able to apply its own external tariff. On 13 March 2019, the Government announced the rates that would apply for the first 12 months after a no-deal exit from the EU.a In line with this, in our stress test we have assumed that:

- for 12 months from November 2019, the announced ‘no-deal’ tariff rates will apply;

- from November 2020 onwards, the UK applies ‘most-favoured nation’ (MFN) tariff rates in line with the current EU common external tariff to all incoming goods not covered by preferential agreements (including goods coming in from the EU); and

- in line with the IMF scenario, the UK secures replacement free trade agreements with third countries currently covered by EU agreements by the time MFN tariff rates apply.

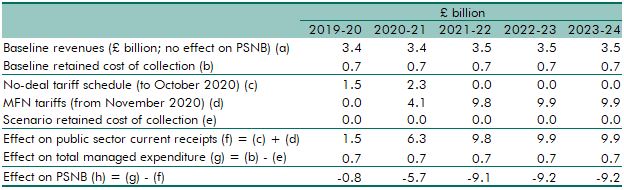

Customs duties receipts on UK imports from outside the EU totalled £3.3 billion in 2018-19. Our March forecast was for this to increase to £3.5 billion by 2023-24. But customs duties are at present remitted to the EU, so do not add to UK current receipts. Their only effect on PSNB comes via the 20 per cent retained to cover the cost of collection. That reduces net expenditure transfers to the EU.b Post-Brexit customs duties receipts would score in the same way as any tax.

The ‘no-deal’ tariff schedule contains tariff lines that cover around £36 billion of imports in 2018-19 (around 7 per cent of all goods imports). Based on a simple application of these tariff rates to detailed goods imports data, we assume that they would raise around £3.8 billion over the 12 months they would be in force. Three quarters of this revenue would come from tariffs on EU goods, and around £5 of every £6 of revenue would come from tariffs on finished cars – the main area to be subject to tariffs outside the agri-food sector.

Application of MFN tariffs from November 2020 to goods coming in from the EU raises more revenue than is raised on goods from the rest of the world. This is mostly because a higher proportion of imports from the EU are goods that face higher MFN duty rates (notably agri-food goods) and goods imports from the EU are worth 20 per cent more than those from the rest of the world. The average MFN tariff that would apply to goods currently imported from the EU is 3.9 per cent, compared with 2.8 per cent for goods from non-EU countries.

Again, a simple application of MFN tariff rates to goods imports yields revenues on goods from the EU of around £6.3 billion a year, in addition to the £3.5 billion from non-EU countries in our March baseline forecast. Removing the 20 per cent of non-EU revenues currently retained to cover costs of collection, the impact of MFN tariffs would be to reduce borrowing in the scenario by around £9.2 billion a year relative to the assumptions in our March forecast.

Table A: Impact of customs duties on PSNB under the fiscal stress test scenario

The figures we have generated for this scenario are illustrative of the potential magnitudes involved, but they should not be taken as a precise central estimate of what the application of these tariff schedules would raise. We have not attempted to account for all the intricacies involved in operating the customs regime or the potentially important behavioural responses of importers and the ultimate consumers of imports. Nor have we made assumptions about any operational challenges, for example regarding the land border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.c We have not modelled non-linear effects of the ‘no-deal’ tariffs, such as tariff-rate quotas, which disproportionately apply to agricultural goods.

Finally, we make no assumptions about the rate of compliance with the regime, or how traders might change their behaviour in response to the tariff schedule. In particular:

- In most tariff schedules – including the EU’s common external tariff – similar tariff rates are applied to similar goods to remove incentives for misclassification of goods to avoid higher tariffs. This is not the case in the no-deal schedule – for example, with an 8 per cent tariff on frozen freshwater fish but a 15 per cent tariff on other frozen fish. This could present opportunities for non-compliance that might be difficult to detect.

- The no-deal tariff schedule imposes very different tariffs on certain components and finished goods, particularly on cars, where a 10 per cent tariff applies to finished products but parts can be imported tariff-free. The extent to which a car can approach completion without being deemed finished and hit by the tariff is not clear. This could prompt producers to import cars in a sufficiently unfinished state to avoid the tariff.

All these and no doubt other factors would need to be considered should we be required to produce a full medium-term customs duties forecast on a no-deal Brexit basis.