The Bank of England’s purchases of gilts under its quantitative easing (QE) programme are undertaken by its subsidiary, the Asset Purchase Facility (APF). Since late 2012-13, the Exchequer received excess cash held in the APF on an ongoing basis. This box summarised the approach used to estimate the fiscal impact of projected APF flows and the changes in these projections since our December 2013 Economic and fiscal outlook forecast. It also highlighted the large uncertainty about the timing and pace of quantitative easing (QE) unwinding.

Since late 2012-13, excess cash held in the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) has been transferred to the Exchequer on an ongoing basis.

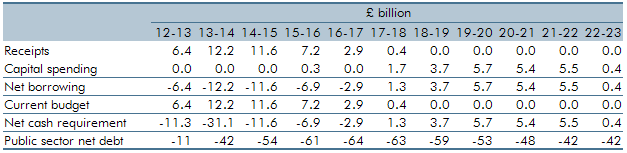

Transfers up to the level of the Bank’s income in the previous year are currently treated as dividends, reducing net borrowing; beyond that, they are financial transactions, reducing the net cash requirement but not borrowing. Any payments made from the Exchequer to the APF are also currently treated as capital grants, increasing net borrowing but not affecting the current budget. This treatment will change following the ONS’s Public Sector Finances Review, to be implemented later this year, and the possible implications are discussed in Annex B.

To estimate the size of future flows, we have to make assumptions about when quantitative easing (QE) will be unwound and how quickly. Our central forecast assumes that Bank Rate follows market expectations, but there is no equivalent guide to expectations for the path of QE. We therefore take a neutral set of assumptions, unchanged since we first included the APF figures in our forecast in December 2012. We assume QE remains at £375 billion and that it begins to be unwound once Bank Rate rises above 1 per cent, with sales evenly paced at £10 billion a quarter thereafter. We also assume redemptions will not be reinvested once sales begin. The first sale is assumed to be in the fourth quarter of 2015, as assumed last December.

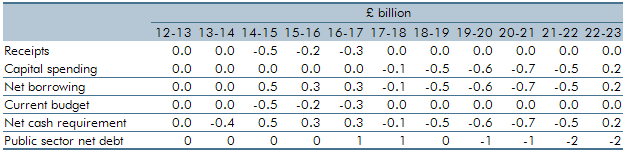

Our projection for the overall net transfer to the Treasury is now £42 billion, up slightly from our December projection of £40 billion. A slightly higher Bank Rate reduces net interest income between 2015-16 and 2017-18, offset later by lower gilt rates, which imply higher gilt prices at the point of sale and therefore smaller capital losses.

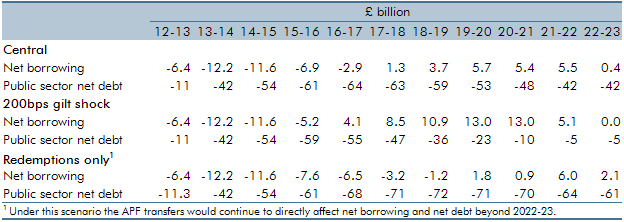

There is huge uncertainty about the timing and pace of QE unwinding and our assumptions should be regarded as a neutral way of illustrating the potential fiscal impact, rather than as a forecast of how the Bank of England is likely to act. Table C also shows two alternative scenarios: the first where gilt rates rise by 200 basis points when QE unwinding starts; and the second where the stock runs down only through redemptions once Bank Rate moves above 1 per cent.

The estimates of the overall transfer to the Exchequer are highly sensitive to changes in gilt rates. In the first scenario the Treasury would receive £61 billion, only to pay back £57 billion over the following years, giving a net transfer of £5 billion. In the second, the Exchequer would continue to receive cash from the APF over the next five years, reducing debt by £72 billion in total, before covering losses over a protracted period. Both scenarios would have much bigger effects beyond our EFO forecasting horizon, which we will revisit in this July’s Fiscal sustainability report.

Table A: Fiscal impact of projected APF flows

Table B: Changes to the fiscal impact of projected APF flows since December

Table C: Fiscal impact of alternative APF scenarios