In addition to its impact on public health, the coronavirus is likely to have a significant adverse effect on the economy and public finances in coming quarters. But neither the size nor the duration of this effect are possible to predict with any confidence. The Chief Medical Officer has declared that an epidemic in the UK is now “likely”, while the Bank of England Governor has said that the shock to the economy “could prove large”.

With large numbers of people potentially sick – or restricting their movements to avoid becoming so – the coronavirus is likely to reduce both the demand for goods and services in the economy and the ability of businesses at home and abroad to supply them. That will temporarily reduce private sector incomes and spending (and hence tax revenues), while putting upward pressure on government spending to help address the outbreak. This implies additional upward pressure on the budget deficit and public debt. But the impact on the public finances over the medium and longer term is likely to be less significant, unless the outbreak inflicts lasting damage on the economy’s supply capacity.

As regards this fiscal event, the Treasury as usual asked us to close our pre-measures forecasts for the economy and the public finances some way in advance of the Budget – on 18 and 25 February respectively – so that it had a stable base against which to finalise its policy decisions. (With the spread of coronavirus then expected to be relatively limited, the impact on the forecasts in this Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) is largely confined to a modestly weaker outlook for growth in world trade and the UK’s export markets.) The only subsequent changes to the forecast were to reflect the Budget measures and other policy announcements since our previous forecast in March 2019 – notably the new migration regime and further rises in the National Living Wage. Under the circumstances, the precise forecasts for the economy and public finances in this EFO can no longer be regarded as central – particularly in the near term – but scrutinising and analysing the impact of the Government’s policy decisions even against this baseline remains informative.

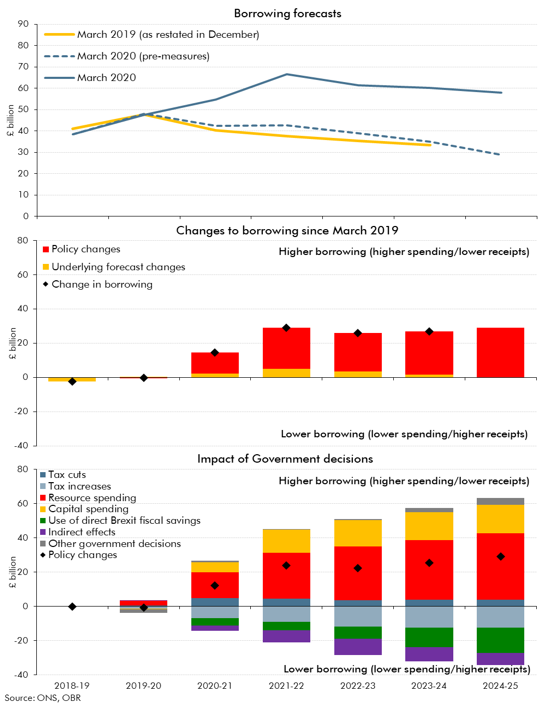

Turning to those policy decisions, the Government has proposed the largest sustained fiscal loosening since the pre-election Budget of March 1992 (which was reversed within months after the UK left the European exchange rate mechanism in September that year). Relative to our pre-measures baseline forecast, the Government’s policy decisions increase the budget deficit by 0.9 per cent of GDP on average over the next five years and add £125 billion (4.6 per cent of GDP) to public sector net debt by 2024-25.

Chart 1: Public sector borrowing: March 2020 versus restated March 2019

The largest components of the fiscal loosening are significant increases in departmental spending plans – for both current and capital. As regards current spending, the Budget completes the reversal of the cuts to real departmental spending per person undertaken by the Coalition Government. The turnaround started in the Conservative Government’s post-election Budget in July 2015, but really took hold with the multi-billion pound NHS settlement in June 2018. The capital spending turnaround is more dramatic still – the Coalition Government’s early cuts (which had been a feature of the previous Labour Government’s March 2010 Budget plans) will have been almost fully reversed this year. Spending is set to be around a third higher at the end of our forecast than in 2010-11.

The net tax rise announced in the Budget reduces borrowing by an average of £5.5 billion a year. This is more than explained by the decision to cancel the planned cut in the main rate of corporation tax from 19 to 17 per cent this April. The Budget also cuts National Insurance and freezes fuel and alcohol duties for a year (again), but restricts eligibility to use cheaper ‘red diesel’ to just a handful of uses. This leaves the receipts-to-GDP ratio on a steadily rising path, reaching its highest level since 1984-85 at the forecast horizon.

Despite a year having passed since our last full forecast, the near-term economic outlook at the time we closed this forecast appeared little changed. That has of course been overtaken by coronavirus. Against our stable but subdued pre-measures forecast baseline, the profile for GDP growth reflects the impact of the Government’s policy decisions. In broad terms, they deliver a boost to demand in the near term that dissipates by the end of the forecast. This overlays a steadily building drag on potential output, largely via the effect of the new migration regime on population growth. GDP growth peaks at 1.8 per cent in 2021, thanks to the fiscal loosening, before easing back to around 1½ per cent a year.

The Government set this Budget against the materially looser set of fiscal rules outlined in the Conservative Party manifesto and confirmed in the Queen’s Speech. Based on these EFO forecasts, the Government would meet its new target of a current budget balance in the third year of our forecast (currently 2022-23) by a margin of £11.7 billion. Public sector net investment (PSNI) rises to 3.0 per cent in 2022-23 and remains there, meeting the ‘maximum investment’ rule. This incorporates our assumption that 20 per cent of the additional capital plans will go unspent (reflecting past experience when governments try to ramp up capital spending quickly). This leaves public sector net debt broadly stable. These assessments reflect the forecasts underpinning them, so near-term risks are to the downside. The extent to which that is true further out, when the rules apply, is unclear.

Formally speaking, the fiscal rules approved by Parliament in the January 2017 Charter for Budget Responsibility remain in force for now – and the Government is not on course to meet them. Our forecast shows a structural budget deficit of 2.4 per cent of GDP in 2020-21, missing the ‘fiscal mandate’ by £9.2 billion. The formal ‘fiscal objective’ is to return the Budget to balance. The Government was on course to achieve a small budget surplus by 2023-24 in our October 2018 pre-measures forecast, but thanks to two expansionary budgets and improved accounting for student loans the deficit is now set to rise and then level off at around £60 billion a year. The Government says that it intends to review the fiscal framework ahead of the next Budget, so the next Charter could incorporate different fiscal targets to those that have underpinned the decisions in the Budget.

The Government’s fiscal plans are rooted in the assumption that its borrowing costs will remain relatively low, as market expectations indeed suggest. Rather than aim for budget balance and a clear decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio – as Philip Hammond did initially as Chancellor – the new administration is content to borrow significant sums on an ongoing basis and merely to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio. This looks sustainable over the medium term on current interest rate and growth forecasts. But, as we have noted in our Fiscal risks reports, financing conditions may not remain this favourable. The debt-to-GDP ratio is twice as high as in the pre-crisis period, the stock of index-linked gilts is much larger and the Bank of England’s asset purchases have shortened the effective maturity of the public debt. Taking both fresh borrowing and the need to roll over existing debt into account, the Government’s gross financing requirement averages around £150 billion a year over the next five years, around half as much again as a share of GDP as in the five years prior to the financial crisis even though the budget deficit is around a fifth smaller. So the public finances are more vulnerable to adverse inflation and interest rate surprises than they were.