Following the upwards revision to our migration forecast, this box explored the implications of higher migration on our central forecasts for tax revenues, spending and borrowing. We also drew on alternative scenarios for migration to illustrate how uncertainty in the migration forecast translates into the fiscal forecast.

This box is based on ONS and OBR data from March 2024 .

Over our five-year forecast, the impact of additional migration on our fiscal forecast is a function of four components:

- the specific fees and charges migrants pay to gain entry to the country. Most migrants, with the exception of asylum seekers and those applying under the EU settlement scheme, pay both the application fees associated with their visa category and the immigration health surcharge (IHS). An average migrant will pay around £1,900 in visa fees and £2,600 on the IHS, and an additional £800 per migrant is paid on the immigration skills charge by sponsoring employers. Total revenues from these sources amount to £4.1 billion per year in our current forecast;

- the general taxes migrants pay as workers, consumers, and residents once they enter the country. As described in Box 2.3, due to new migrants being concentrated among those of prime working age, we estimate they have a slightly higher participation rate than the resident population. Beyond this, we assume new migrants have the same employment, consumption, and residential patterns as residents, and as such pay similar levels of wider taxation, so that their per capita contribution is close to the average UK adult at around £19,500 per year over our forecast;

- the welfare benefits for which migrants are eligible, which are limited for most migrants during at least their first five years in the country. Apart from returning UK or Irish citizens or those who come via humanitarian routes, most new migrants are initially ineligible for most benefits. Eligibility for state pensions requires at least 10 years of qualifying national insurance contributions, meaning almost all new migrants will also initially be ineligible. The impact of new migrants on welfare spending over our five-year forecast is therefore very small;a and

- the public services they use in the UK. While migrants will consume public services such as education, healthcare, and transport, there is no direct link between the size of the population and the money allocated for departmental spending on public services. Currently, departmental expenditure limits (DELs) for each major public service are fixed by the Government in nominal terms up to the end of the Spending Review period in 2024-25. Thereafter, the Government provides us with an assumption for growth in total current and capital spending, but no detailed department-by-department plans. As discussed in paragraph 4.54, as the Government has not adjusted these limits or assumptions for the increases in population, implied real public service spending per person has fallen since the plans were set out in October 2021.

Therefore, the net fiscal impact of the 350,000 (around 300,000 adults) increase in net migration across our central forecast above Autumn is to:

- increase specific fees and charges paid by those additional migrants by £0.3 billion in 2028-29;

- increase general tax revenue paid by those additional migrants by £6.2 billion in 2028-29;

- leave welfare spending largely unchanged as very few of the new migrants will be eligible by 2028-29;

- leave public services spending largely unchanged, but reduce DEL spending per person by £40 in 2028-29 and increase the pressure on those services; and

- therefore deliver a net reduction in borrowing of around £7.4 billion by 2028-29, taking account of lower spending on debt interest as well.

Fiscal implications of alternative migration scenarios

To explore the fiscal implications of the uncertainty around future migration levels we draw on the higher and lower migration scenarios, described in Box 2.3, in which net migration is 200,000 a year higher or lower than in our central forecast. These scenarios assume that extra migrants have the same levels of participation and hourly productivity as assumed in our central forecast. We then make different assumptions about how spending on public services reacts to levels of net migration.

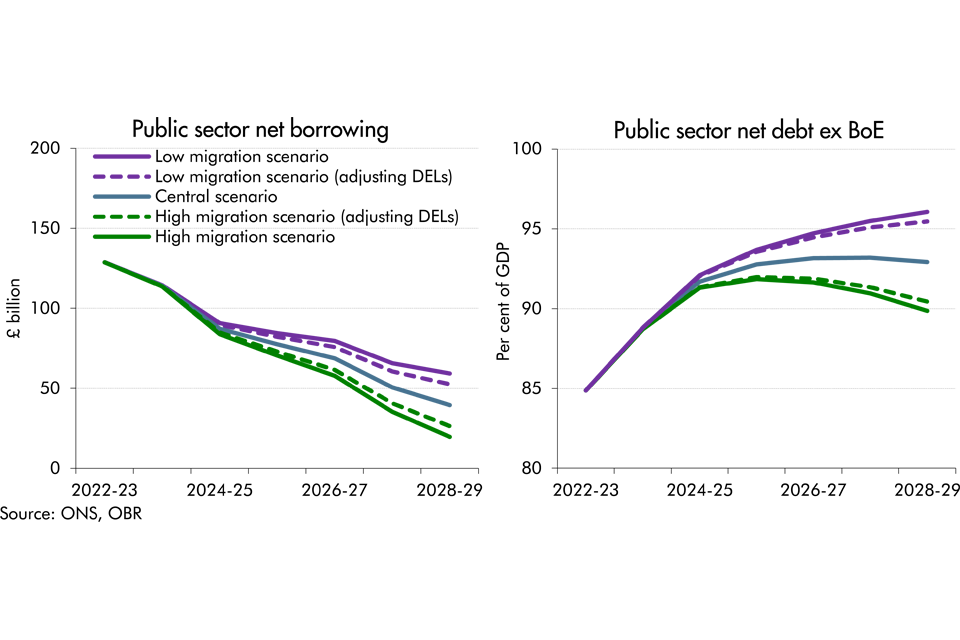

No adjustment to departmental spending on public services (DEL): In the higher migration scenario, receipts are £18.0 billion higher by the forecast horizon with contributions from both migration specific fees (£0.5 billion) and general taxation (£17.5 billion). With an assumption that migrants receive no welfare and that DEL spending is not adjusted to reflect the increase in population, the only spending impact is £1.9 billion lower debt interest spending from the smaller stock of debt. Overall, borrowing is estimated to be £19.9 billion lower and debt 3.1 per cent of GDP lower in 2028-29. The lower migration scenario is symmetric to this, with lower receipts and spending, meaning that borrowing is £19.9 billion higher and debt 3.1 per cent of GDP higher in 2028-29.

Adjustment to departmental spending on public services (DEL): In the higher migration scenario, if the Government responded to additional migration by keeping departmental spending per person unchanged compared to our central forecast this would require an estimated extra £8.1 billion of expenditure by 2028-29. This may overstate the spending pressures because new migrants tend to be concentrated among those of working age and include fewer children and old people than the resident population. This would reduce the per capita pressures placed on services such as schools and hospitals. Adjusting for this we estimate that providing equivalent service provision to the additional migrants in the high scenario would require an additional £6.1 billion in 2028-29. On this basis, in this scenario a portion of the higher receipts generated by the additional migrants is offset by higher spending, so that while migration still improves the public finances it does so by less than in the unadjusted DEL scenario, with borrowing £13.1 billion lower and debt 2.5 per cent of GDP lower by 2028-29. The lower migration scenario has the opposite effect with borrowing and debt £13.1 billion and 2.5 per cent of GDP higher.

Chart H: Borrowing and PSND ex BoE in the migration scenarios

These scenarios are a simplification and are highly uncertain. They are sensitive to assumptions around the composition of migrants including their age, skill, and average earnings. And they are dependent on the levels of departmental spending the government sets as a response to the higher population. They also only consider the economic and fiscal impacts over our five-year forecast horizon. The overall long-term impact of migration on the public finances is more uncertain. The fiscal impacts of migration are likely to become less beneficial over time, reflecting that after a minimum of 5-years, migrants can apply for indefinite leave to remain and therefore become eligible for welfare benefits. If migrants stay in the UK into older age, there would also be greater pressures on pensions and health spending and lower tax revenues as they retire.

This box was originally published in Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2024