More than a year on from its start, the coronavirus pandemic continues to exact a heavy toll in lives and livelihoods. Around the globe, more than 100 million people have had the virus and around 2½ million have died from it, and world GDP fell by 3½ per cent in 2020 as governments imposed public health restrictions in an attempt to control the virus. The UK has been hit particularly hard. Following a resurgence of infections over the winter, around 1 in 5 people have so far contracted the virus, 1 in 150 have been hospitalised, and 1 in 550 have died, the fourth highest mortality rate in the world. And GDP fell 9.9 per cent in 2020, the largest decline in the G7. While output partially recovered in the second half of last year – and somewhat more strongly than we previously thought – the latest lockdown and temporary disruption to EU-UK trade at the turn of the year is expected to result in output falling again in the first quarter of this year.

The pandemic has, however, also spurred a global scientific effort to develop new and effective vaccines at unprecedented speed, with the UK in the vanguard of their discovery and rollout. More than 200 million people worldwide have already received their first dose of one of those vaccines. In the UK, that figure has topped 20 million – more than a third of all adults and the fourth highest vaccination rate worldwide. Early evidence from the UK and other countries indicates that the vaccines are broadly as effective in reducing illness and death as suggested in clinical trials. The Government aims to have offered a first dose to everyone over 50 or at risk by 15 April and to all adults by 31 July, slightly earlier than assumed in our November central forecast.

The rapid rollout of effective vaccines offers hope of a swifter and more sustained economic recovery, albeit from a more challenging point than we forecast in November. The easing of public health restrictions in line with the Government’s 22 February Roadmap should permit a rebound in consumption and output through this year, partially supported by the release of extra savings built up by households during the pandemic. GDP is expected to grow by 4 per cent in 2021 and to regain its pre-pandemic level in the second quarter of 2022, six months earlier than we forecast in November. Unemployment still rises by a further 500,000 to a peak of 6.5 per cent at the end of 2021, but the peak is around 340,000 less than the 7.5 per cent assumed in our November forecast, thanks partly to the latest extension of the furlough scheme. The pandemic is nevertheless still expected to lower the supply capacity of the economy in the medium term by around 3 per cent relative to pre-virus expectations.

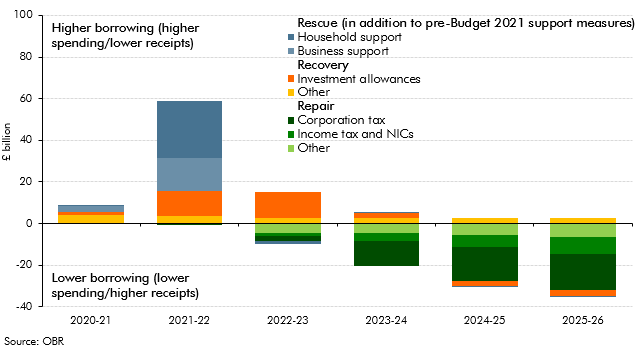

Faced with an economy that is weaker in the near term but rebounding faster than we forecast in November, the Chancellor has done three things in this Budget. First, he has extended the virus-related rescue support to households, businesses and public services by a further £44.3 billion, taking its total cost to £344 billion. Second, he has boosted the recovery, most notably through a temporary tax break costing more than £12 billion a year that encourages businesses to bring forward investment spending from the future into this year and next. Third, as the economy normalises, he has taken a further step to repair the damage to the public finances in the final three years of the forecast by raising the headline corporation tax rate, freezing personal tax allowances and thresholds, and taking around £4 billion a year more off annual departmental spending plans, raising a total of £31.8 billion in 2025-26 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: The impact of Budget measures on public sector net borrowing

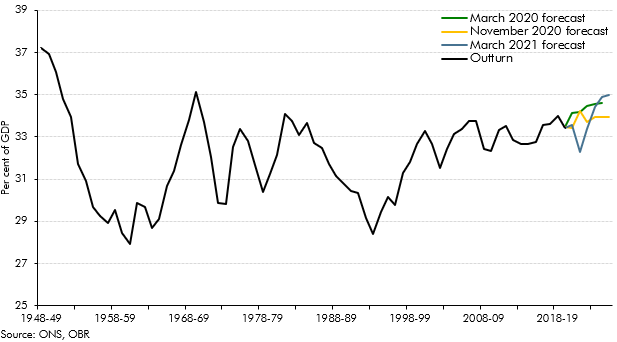

The tax rises announced in this Budget increase the tax burden from 34.0 to 35.0 per cent of GDP in 2025-26, its highest level since Roy Jenkins was Chancellor in the late 1960s (Chart 2). Over half of this increase is as a result of a 6 percentage point increase in the corporation tax rate to 25 per cent. This brings the headline corporation tax rate back into line with the advanced economy average but still well below its long-run historical average in the UK of around 35 per cent. However, the widening of the tax base over the past decade means that this relatively modest increase in the headline rate leaves corporation tax raising 3.2 per cent of GDP in revenue by 2025-26, its highest since 1989-90. Freezes to the income tax personal allowance and higher rate threshold for four years bring 1.3 million people into the tax system and create 1 million higher rate taxpayers by 2025-26.

Chart 2: Tax as a share of nominal GDP

As the economy reopens and emergency fiscal support is withdrawn, government borrowing is forecast to fall from a peacetime high of £355 billion (16.9 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21 to £234 billion (10.3 per cent of GDP) in 2021-22 (still higher than the 2009-10 peak at the height of the financial crisis). In 2022-23, as fiscal policy moves from rescue to recovery, the deficit falls back to £107 billion (4.5 per cent of GDP). Thereafter, as policy focuses on repair and taxes rise, borrowing falls to £74 billion (2.8 per cent of GDP) in 2025-26.

Headline debt tops 100 per cent of GDP this year and remains above that level throughout our forecast. Underlying debt (excluding the Bank of England) peaks at 97.1 per cent of GDP in 2023-24 before falling back to 96.8 per cent of GDP by the end of the forecast. Despite the stock of debt reaching its highest level as a share of the economy since 1958-59, the costs of servicing that debt falls to a historic low of just 2.4 per cent of total revenues thanks to the decline in interest rates. Unlike previous post-crisis Chancellors who cut back capital spending to reduce borrowing and rein in debt, this one has left in place the significant increase in public investment, from 1.9 per cent of GDP last year to 2.7 per cent of GDP by 2025-26, that he announced a year ago.

The Chancellor has not set new fiscal targets in this Budget (despite two of the existing ones expiring this month) and is instead proceeding with the review of the fiscal framework proposed in last year’s Budget. But the absence of formal fiscal targets does not mean that the Chancellor has not been guided by particular metrics when selecting his medium-term Budget policies. The tax rises and spending cuts he has announced are sufficient to eliminate all but a £0.9 billion current budget deficit in 2025-26, while they are just enough to see underlying public sector net debt as a share of GDP fall by a similarly small margin of £0.7 billion in 2024-25 and £4.1 billion in 2025-26.

Uncertainty around the economic outlook remains considerable, with the course of the pandemic still the greatest single risk. A quicker rollout of vaccines with greater effectiveness in reducing infection and illness, the development of new therapies and treatments, or a faster rundown in household savings built up during the pandemic could deliver a swifter economic recovery and less medium-term scarring. Against that, setbacks in the rollout of the vaccines, the emergence of new vaccine-resistant variants, or reduced compliance with residual public health restrictions could force governments back into periodic lockdowns, with more adverse consequences for the economy in the short and medium term. So, the upside and downside scenarios set out in our November Economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) remain a reasonable guide to the range of possible future outcomes.

Assuming the Chancellor can maintain the tax burden close to historic highs, the main fiscal risks come from the legacy of the pandemic for public services. While public spending is set to be 2 per cent higher as a share of GDP in 2025-26 than in 2019-20, most of this reflects increases in health, education and public investment announced before the pandemic. The Government’s spending plans make no explicit provision for virus-related costs beyond 2021-22, despite its Roadmap recognising that annual vaccination programmes and continued testing and tracing are likely to be required. The Government will also need to decide how to catch up on services disrupted by the virus, notably the backlogs in non-urgent procedures in the NHS that have built up and the months of lost or impaired schooling for some pupils.

Faced with these post-pandemic pressures, the Government has so far cut more than £15 billion a year from departmental resource spending from 2022-23 onwards, setting up a challenging Spending Review later this year. The public finances are also much more sensitive than they were to rises in short-term interest rates, due to a combination of the higher debt stock and its effective refinancing by the Bank of England through quantitative easing, which has shortened the median maturity public debt from more than seven years before the financial crisis to less than two today. To illustrate this risk, the 30 basis point increase in interest rates that has happened since we closed our forecast on 5 February would already add £6.3 billion to the interest bill in 2025-26 published in this document. All else equal, that would be enough to put underlying debt back on a rising path relative to GDP in every year of the forecast.